6.3 Access to adequate water supplies as a human right

6.3–

Approximately 5,000 years ago, two Mesopotamian city-

The environmental scientist Peter H. Gleick pointed out in 1999 that water has not been included as a right in most international conventions on human rights. Although these conventions recognize the human right to life and to adequate food, both of which depend on access to water, they have managed to omit the life-

Daily Water Needs

If you were limited to 50 liters of water per day, how would you cope with everyday tasks?

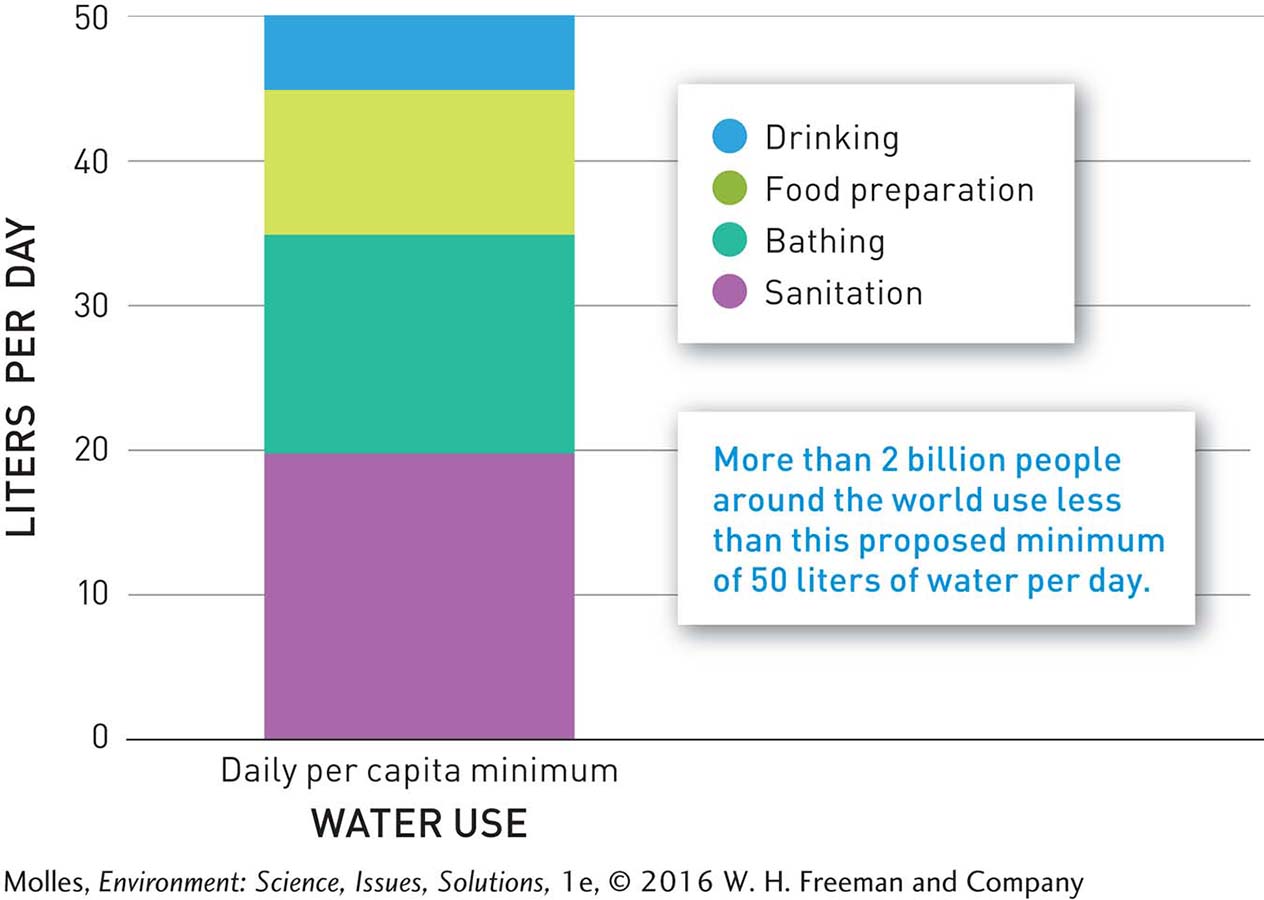

Defining the minimum amount of water a person needs to live is not easy. First off, it depends on the climate. People living in warmer climates will obviously need more water than people living in cooler climates. But it also depends on the individuals, how old they are, how much they weigh, and how active they are. An adult living in a moderate climate and engaging in moderate levels of activity needs to consume about 3 to 5 liters of water per day. Daily water requirements increase with temperature, activity level, and body size. Furthermore, drinking is only one of many ways we use water. We use water to brush our teeth, wash our hands and clothing, and clean our dishes. Allowing for these purposes, Gleick, the founder of the Pacific Institute in Oakland, California, has suggested a volume of about 50 liters (13.2 gallons) per day, budgeted as follows: 20 liters for sanitation services (mainly sewage disposal), 15 liters for bathing, 10 liters for food preparation, and 5 liters for drinking (Figure 6.6). The World Health Organization estimates that daily access to between 50 and 100 liters of water is the minimum to ensure adequate sanitation and health.

163

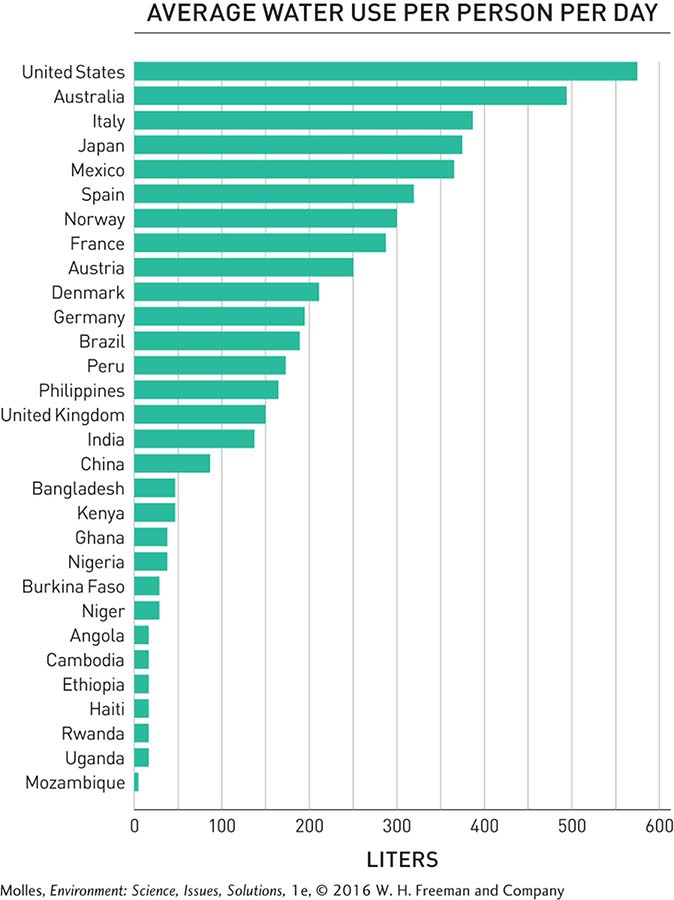

Relative to the amount of water used in the United States and other developed countries, 50 to 100 liters isn’t much (Figure 6.7). Even so, according to the United Nations, some 2.6 billion people around the world lack access to sufficient water to meet their basic sanitation needs, and 900 million don’t have safe drinking water. Even in places where there is theoretically enough water for residents, they often have no good way to obtain it. The average distance that women and children in Asia walk to obtain water is 6 kilometers (3.7 miles), making less time available for other work and for education.

Water as a Human Right: The Challenges

In 2010 the UN General Assembly at last adopted a resolution recognizing “the human right to water and sanitation.” The resolution passed by a vote of 122 nations in favor, none against, with 41 nations abstaining. Although the resolution passed, the debate over recognizing water as a human right continues.

Many of the countries that abstained during the UN vote to recognize water as a human right—

What if, for example, some nations were required to transfer water across international boundaries. Would Canada then be obligated to transfer water to meet the needs of a growing U.S. population? Another concern is that if access to water is a human right, who bears the responsibility of providing water and paying for the infrastructure to do so? Meanwhile, those in favor of water as a human right counter that the right to water is part of the public trust that belongs to all species. As we move into the future, the proponents of these opposing views will have to engage in an international dialogue, which may lead to a mix of governmental and private business approaches that address the water needs of more people.

164

Think About It

If water is guaranteed as a human right, how much water should people be guaranteed?

Should water-

rich regions contribute water to heavily populated arid or semi- arid regions? Explain why or why not. If water can be considered a human right, should this right be addressed at the expense of other species or the natural ecosystems of a region—

for example, endangered fish and amphibian species living in arid regions?