6.7 Water conservation can increase water use efficiency substantially

6.7–

173

How would you like to drink a nice, tall glass of toilet water? In May 2014 the city of Wichita Falls, Texas, began recycling 5 million gallons of sewage, treating it, and sending it right back into the faucets of its residents. The program was a last-

It pays to fix dripping faucets. Water losses from leaks in water supply systems can range anywhere from 10% to 30% of the total water volume pumped. These losses occur in both modern and old water systems and in cities small and large. The water supply system of Mexico City loses enough water through leaks to supply Rome with all the water it needs!

Water Conservation in a Large City

If all the water supply and wastewater lines in New York City were laid out, they would stretch to California and back, twice (Figure 6.22). Keeping them in shape is a monumental task. In the 1970s, flows of water and wastewater in the New York City system began to exceed safety limits and push pollution maximums. In response, the city decided to conserve water.

174

First on their list of priorities was a public education campaign to inform water users of the need for, and means to achieve, conservation. The campaign included over 200,000 door-

What are some implications of water conservation achieved by simply making water meters accessible to individual water users?

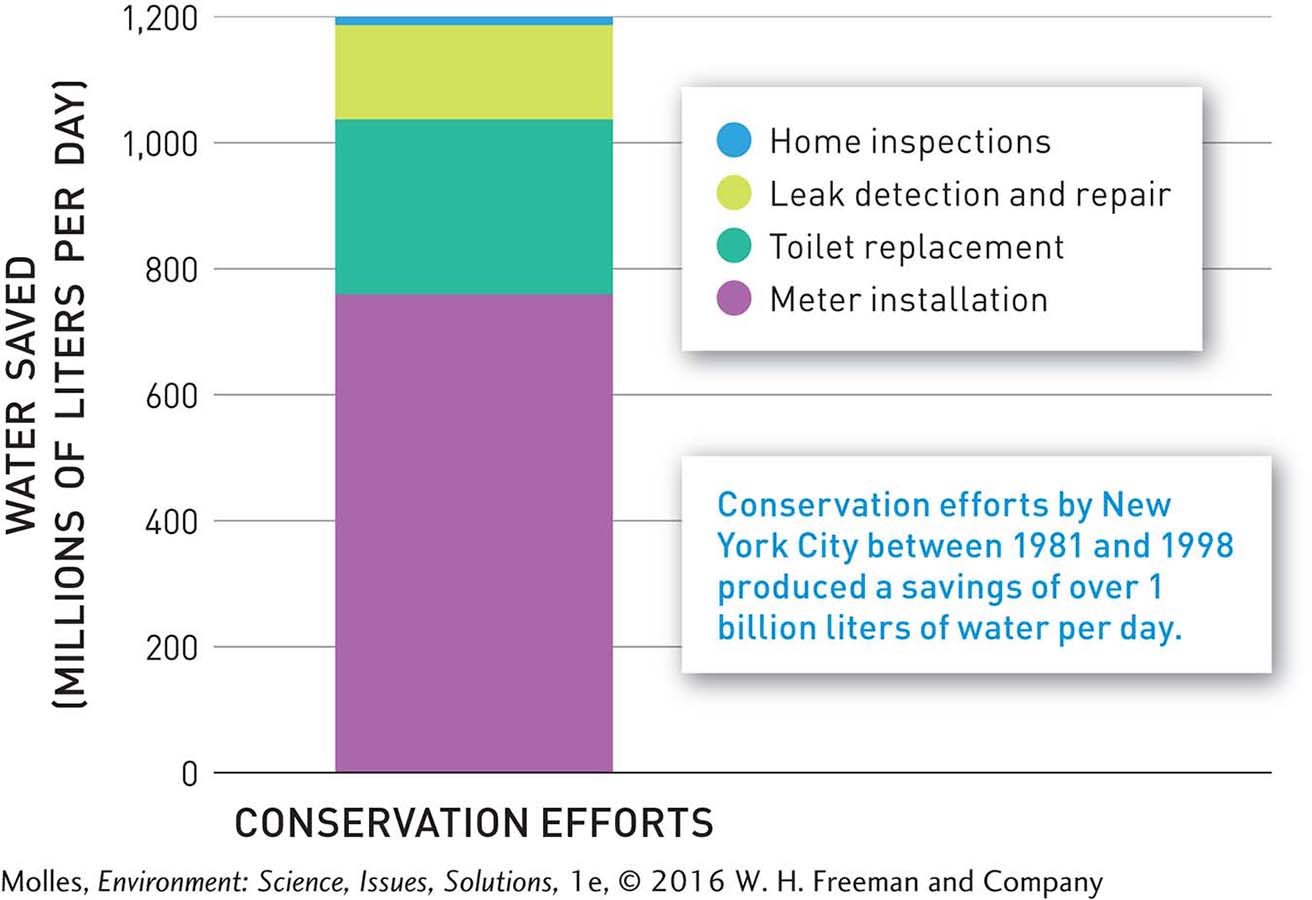

New York City’s conservation efforts saved nearly 1.2 billion liters (320 million gallons) of water per day (Figure 6.23). Surprisingly, the greatest volume of water saved was associated with installing water meters in unmetered residences. It appears that when given the means to keep track, many residents reduced their water use.

How could you personally contribute to water savings in your community? Prioritize the steps you would take to conserve water.

Gauging Conservation Progress

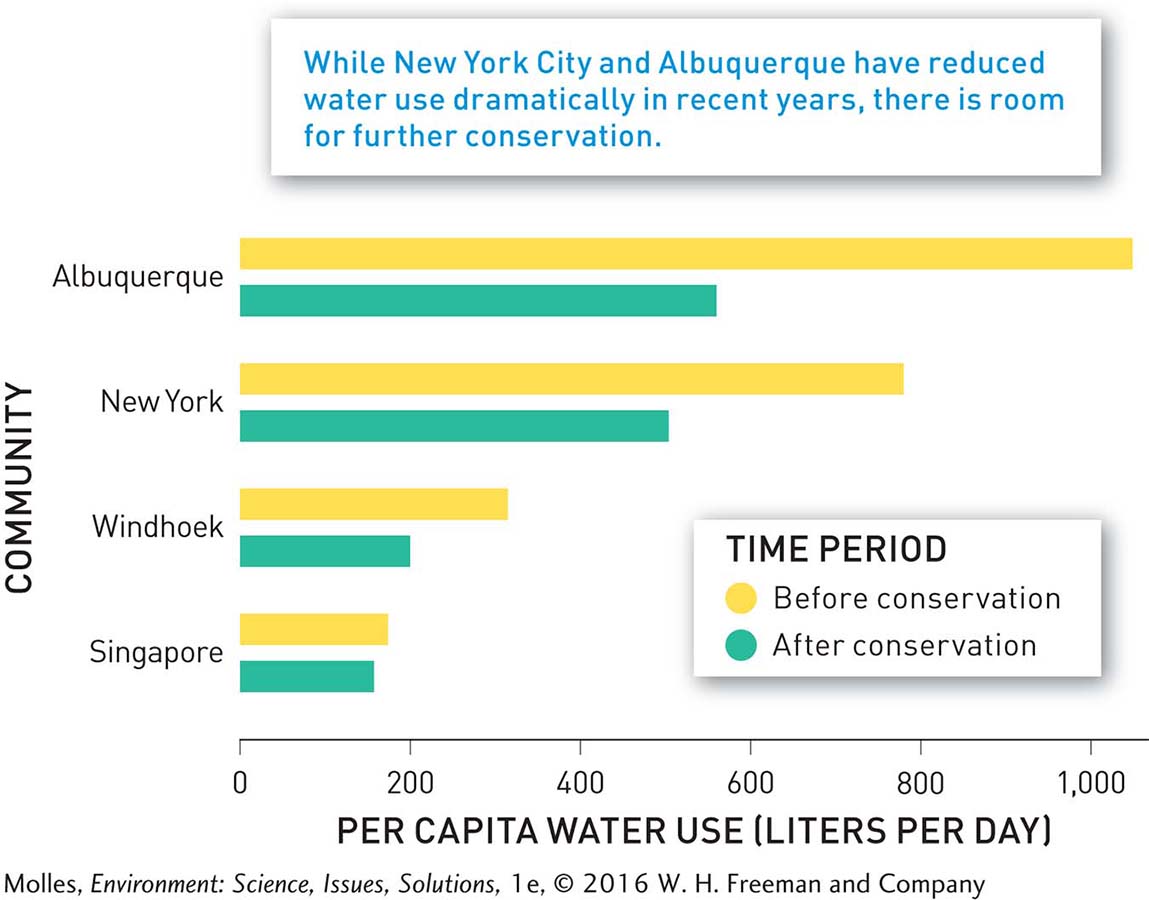

Other municipal conservation programs around the world have resulted in impressive reductions in water use. From 1988 to 2013, water conservation efforts in Albuquerque, New Mexico, reduced daily per capita water use from 1,056 liters (279 gallons) to 560 liters (148 gallons). Meanwhile, the residents of Windhoek, the bone-

While the results of these conservation efforts are impressive, water consumption in these three cities far outpaces that in the Republic of Singapore, a tiny, densely populated island faced with severe water constraints. Its 20 major reservoirs supply only half of its water needs, and it must purchase the rest of its water from nearby Malaysia. Consequently, it has focused its efforts on conservation and reduced per capita water consumption from 172 liters (45.4 gallons) per day in 1995 to 154 liters (40.7 gallons) per day in 2013. The Singapore water authority believes that further progress is possible and aims to reduce consumption to 147 liters per day by 2020 through its water conservation campaign. One suggestion made by the Singaporean Department of Environment and Water is for all residents to save water by reducing their length of showers by 1 minute.

Conservation by Commercial and Institutional Buildings

Commercial and institutional buildings, including office buildings, hotels, commercial laboratories, and university buildings, are major users of water. Conservation efforts have produced large water savings and reduced operating costs in all these types of buildings. Of these, water conservation by hotels may be the best documented and the most familiar. The hotel industry is responsible for 15% of commercial and institutional water consumption in the United States. Three-

175

These efforts have produced impressive water savings. The Kalaloch Lodge in the Olympic National Park in Washington set a goal of reducing its water use by 40% by the year 2020. In addition to making its water system more efficient, Kalaloch Lodge issued a 5-

Think About It

How do the levels of water consumption in the four communities shown in Figure 6.24 compare with the proposed minimum consumption proposed as a water right (see page 163)?

What are the water use issues in your community and how are they being addressed?

How are water conservation programs aimed at private residences and at hotels similar? How might they differ to be most effective?