HOW DO WE KNOW?

FIG. 22.7

452

Can vicariance cause speciation?

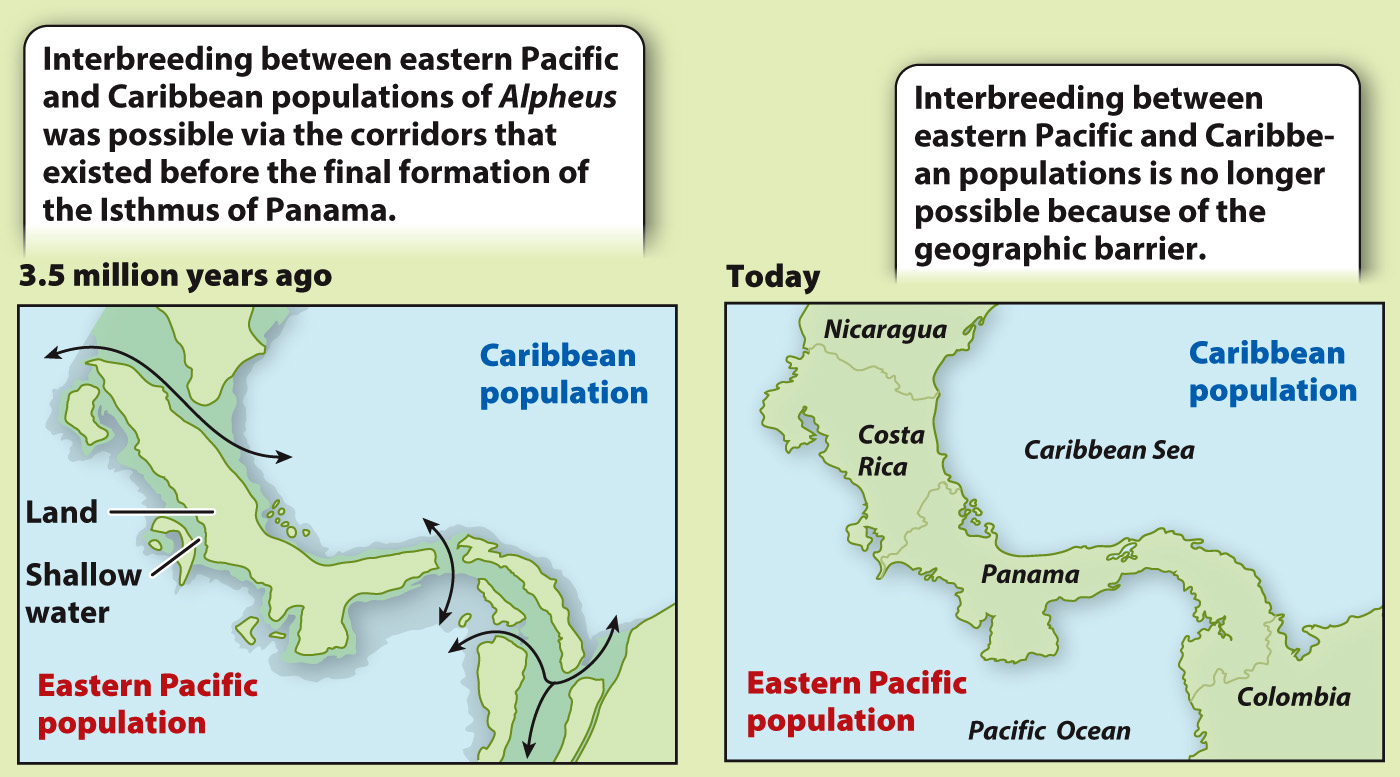

BACKGROUND Three and a half million years ago, the Isthmus of Panama was not completely formed. Several marine corridors remained open, allowing interbreeding between marine populations in the Caribbean and the eastern Pacific. Subsequently, the gaps in the isthmus were plugged, separating the Caribbean and eastern Pacific populations and preventing gene flow between them.

HYPOTHESIS Nancy Knowlton and her colleagues hypothesized that patterns of speciation would reflect the impact of the vicariance resulting from the closing of the direct marine connections between the Pacific and the Caribbean. Specifically, they predicted that each ancestor species (from the time before the formation of the isthmus) split into two “daughter” species, one in the Caribbean and the other in the Pacific. The closest relative of each current Pacific species, then, is predicted to be a Caribbean species (and vice versa).

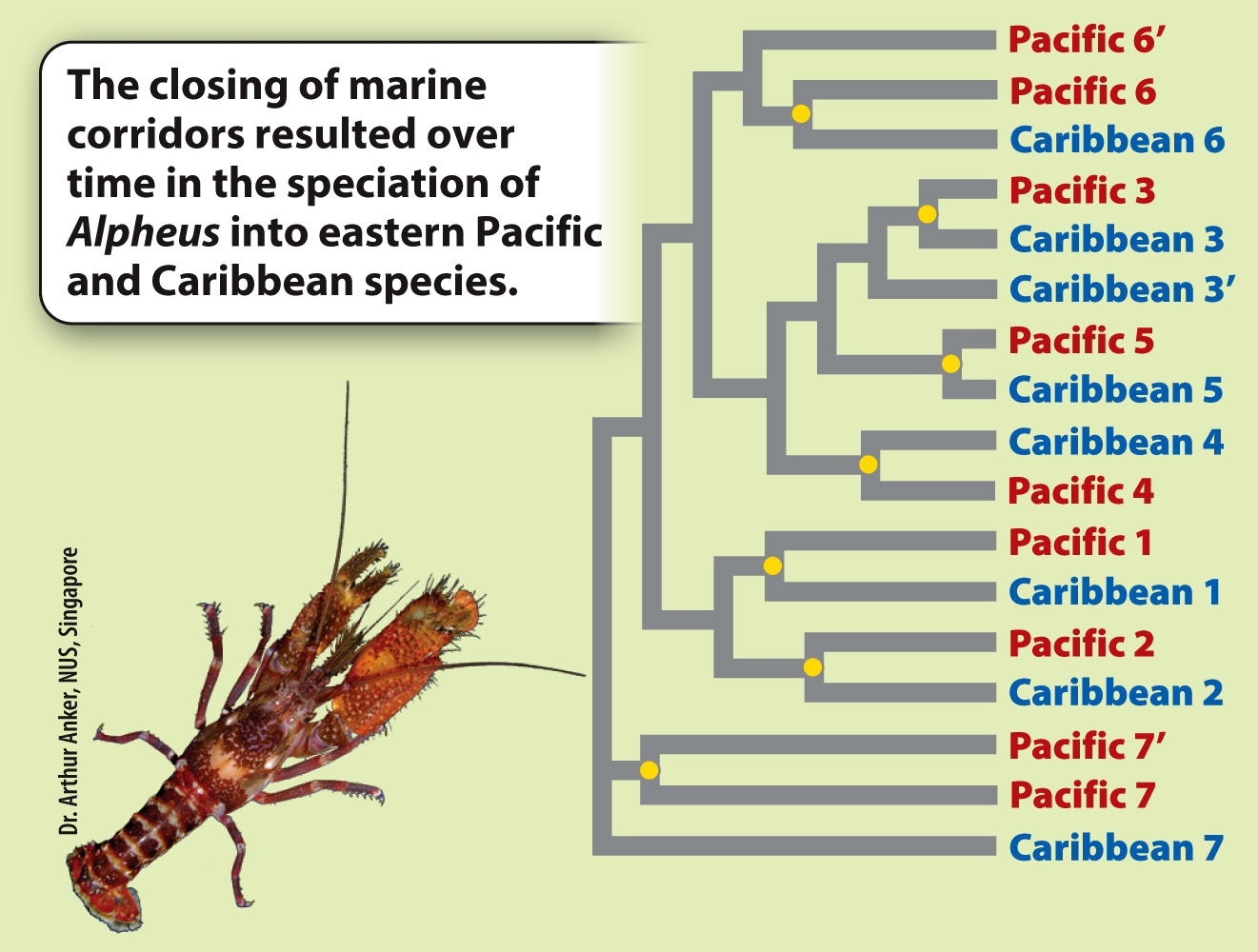

EXPERIMENT This study focused on 17 species of snapping shrimp in the genus Alpheus, a group that is distributed on both sides of the isthmus. The first step was to sequence the same segment of DNA from each species. The next step was to compare those sequences in order to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships among the species.

RESULTS The phylogeny reveals that species show a distinctly paired pattern of relatedness: The closest relative of each species is one from the other side of the isthmus.

CONCLUSION That we see these consistent Pacific/Caribbean sister species pairings strongly supports the hypothesis that the vicariance caused by the formation of the isthmus has driven speciation in Alpheus. Each Pacific/Caribbean pairing is derived from a single ancestral species (indicated by a yellow dot) whose continuous distribution between the Caribbean and eastern Pacific was disrupted by the formation of the isthmus. Here, we see striking evidence of the role of vicariance in multiple speciation events.

FOLLOW-

SOURCE Knowlton, N., et al. 1993. “Divergence in Proteins, Mitochondrial DNA, and Reproductive Compatibility Across the Isthmus of Panama.” Science 260 (5114):1629–