The structure of skin relates to its function.

To start our investigation of the cytoskeleton, cell junctions, and the extracellular matrix, let’s consider a community of cells very familiar to all of us—

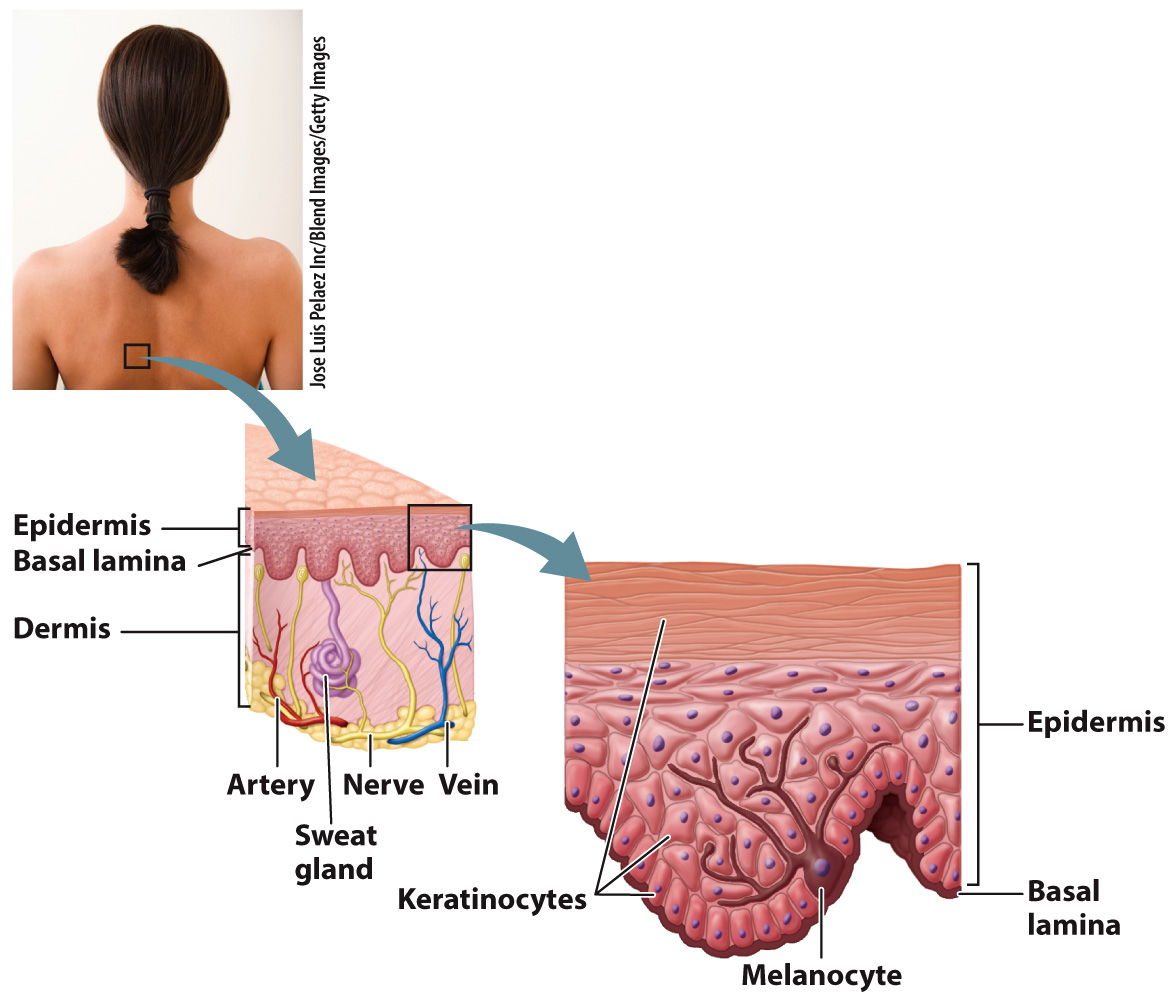

As you can see in Fig. 10.2, the epidermis is several cell layers thick. Cells arranged in one or more layers are called epithelial cells and together make up a type of animal tissue called epithelial tissue. Epithelial tissue covers the outside of the body and lines many internal structures, such as the digestive tract and vertebrate blood vessels. The epidermal layer of skin is primarily composed of epithelial cells called keratinocytes. The epidermis also contains melanocytes that produce pigment that gives skin its coloration.

Keratinocytes in the epidermis are specialized to protect underlying tissues and organs. They are able to perform this function in part because of their elaborate system of cytoskeletal filaments. These filaments are often connected to the cell junctions that hold adjacent keratinocytes together. Cell junctions also connect the bottom layer of keratinocytes to a specialized form of extracellular matrix called the basal lamina (also called the basement membrane, although it is not in fact a membrane), which underlies and supports all epithelial tissues.

200

The second layer of skin, the dermis, is made up mostly of connective tissue, a type of tissue characterized by few cells and substantial amounts of extracellular matrix. The main type of cell in the dermis is the fibroblast, which synthesizes the extracellular matrix. The dermis is strong and flexible because it is composed of tough protein fibers of the extracellular matrix. The dermis also has many blood vessels and nerve endings.

We will come back to the skin several times in this chapter to show more precisely how these multiple connections among cytoskeleton, cell junctions, and the extracellular matrix make the skin a watertight and strong protective barrier.