Most cancers require the accumulation of multiple mutations.

Most human cancers require more than the overactivation of one oncogene or the inactivation of a single tumor suppressor. Given the multitude of different tumor suppressor proteins that are produced in the cell, it is likely that one will compensate for even the complete loss of another. Cells have evolved a redundant arrangement of these control mechanisms to ensure that cell division is properly regulated.

239

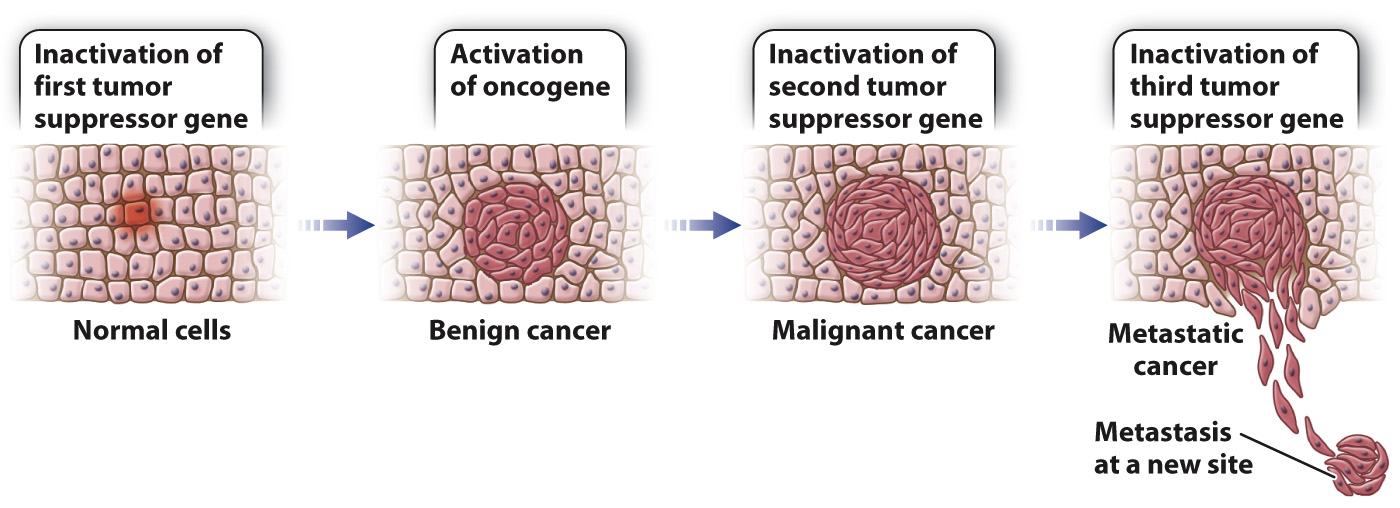

When several different cell cycle regulators fail, leading to both the overactivation of oncogenes and the loss of tumor suppressor activity, cancer will likely develop. The cancer may be benign, which means that it is relatively slow growing and does not invade the surrounding tissue, or it may be malignant, which means that it grows rapidly and invades surrounding tissues. In many cases of malignant colon cancer, for example, tumor cells contain at least one overactive oncogene and several inactive tumor suppressor genes (Fig. 11.20). The gradual accumulation of these mutations over a period of years can be correlated with the stepwise progression of the cancer from a benign form to full malignancy.

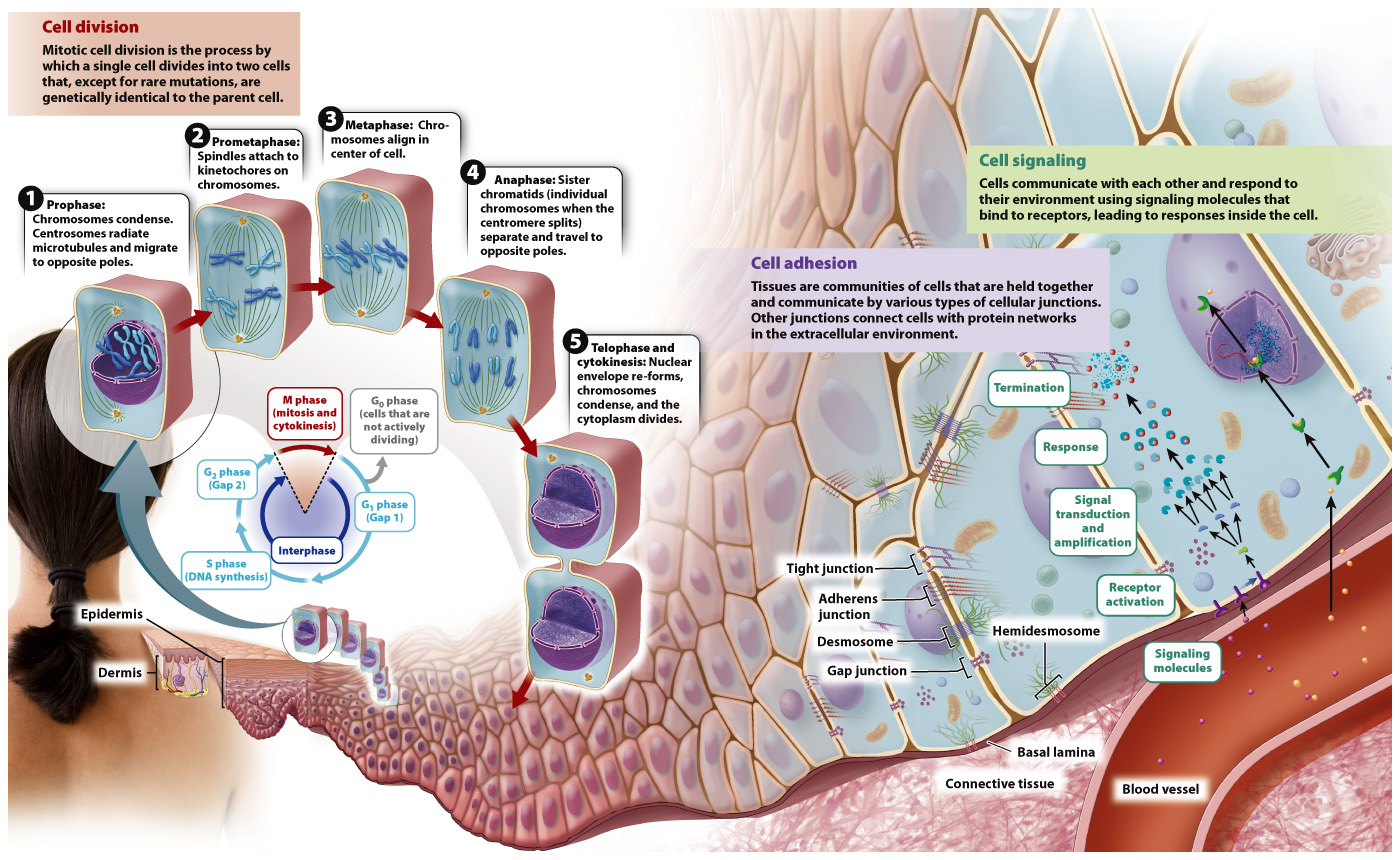

Taken together, we can now define some of the key characteristics that make a cell cancerous. Uncontrolled cell division is certainly important, but given the communities of cells and extracellular matrix we have discussed over the last few chapters, additional characteristics should also be considered. In 2000, American biologists Douglas Hanahan and Robert Weinberg wrote a paper in the journal Cell (Cell 100: 57–

Considered in this light, a cancer cell is one that no longer plays by the rules of a normal cellular community. Cancer therefore serves to remind us of the normal controls and processes that are required to allow cells to exist in a community. These processes, which work together, are summarized in Fig. 11.21.

240

VISUAL SYNTHESIS

241