The host range of a virus is determined by viral and host surface proteins.

Although viruses show great diversity in their genomic nucleic-

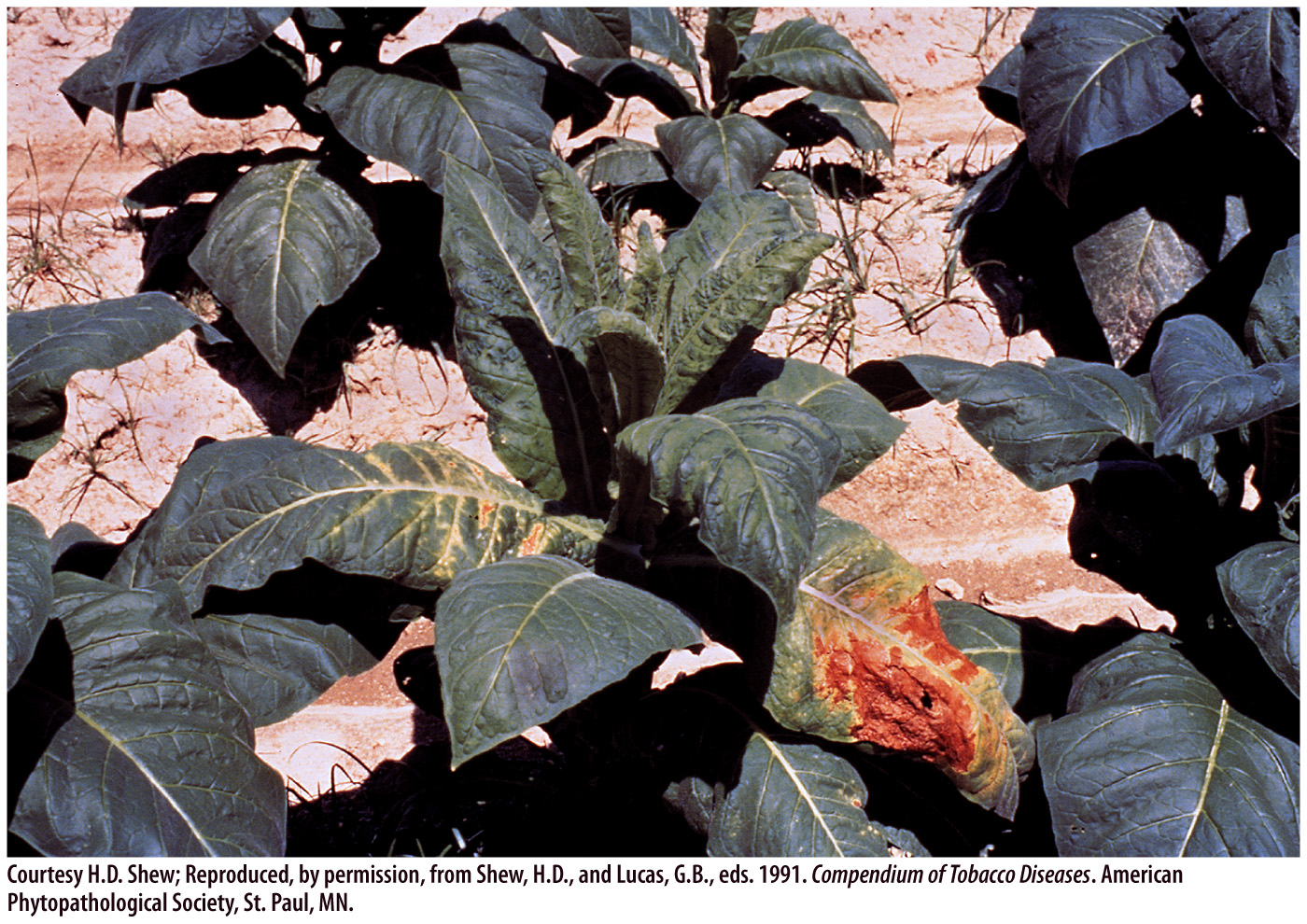

All known cells and organisms are susceptible to viral infection, including bacteria, archaeons, and eukaryotes. A cell in which viral reproduction occurs is called a host cell. Some viruses kill the host cell; others do not. Although viruses can infect all types of living organism, a given virus can infect only certain species or types of cell. At one extreme, a virus can infect just a single species. Smallpox, which infects only humans, is a good example. In cases like this, we say that the virus has a narrow host range. For other viruses, the host range can be broad. For example, rabies infects many different types of mammal, including squirrels, dogs, and humans. Similarly, tobacco mosaic virus, a plant virus, infects more than 100 different species of plants (Fig. 13.17). No matter how broad the host range, however, plant viruses cannot infect bacteria or animals, and bacterial viruses cannot infect plants or animals.

Host specificity results from the way that viruses gain entry into cells. Proteins on the surface of the capsid or envelope (if present) bind to proteins on the surface of host cells. These proteins interact in a specific manner, so the presence of the host protein on the cell surface determines which cells a virus can infect. For example, a protein on the surface of the HIV envelope called gp120 (encoded by the env gene; see Fig. 13.7) binds to a protein called CD4 on the surface of certain immune cells (Chapter 43), so HIV infects these cells but not other cells.

Following attachment, the virus gains entry into the cell, where it can replicate by using the host cell machinery to make new viruses. In some cases, the viral genome integrates into the host cell genome (Chapter 19).

The host range of a virus can change because of mutation and other mechanisms (Chapter 43). For example, avian, or bird, flu is a type of influenza virus that was once restricted primarily to birds but now can infect humans. The first reported case in humans was in 1996, and the disease has since spread widely. Similarly, HIV once infected only nonhuman primates, but its host range expanded in the twentieth century to include humans. Canine distemper virus, which infects dogs, expanded its host range in the early 1990s, leading to the infection and death of lions in Tanzania.