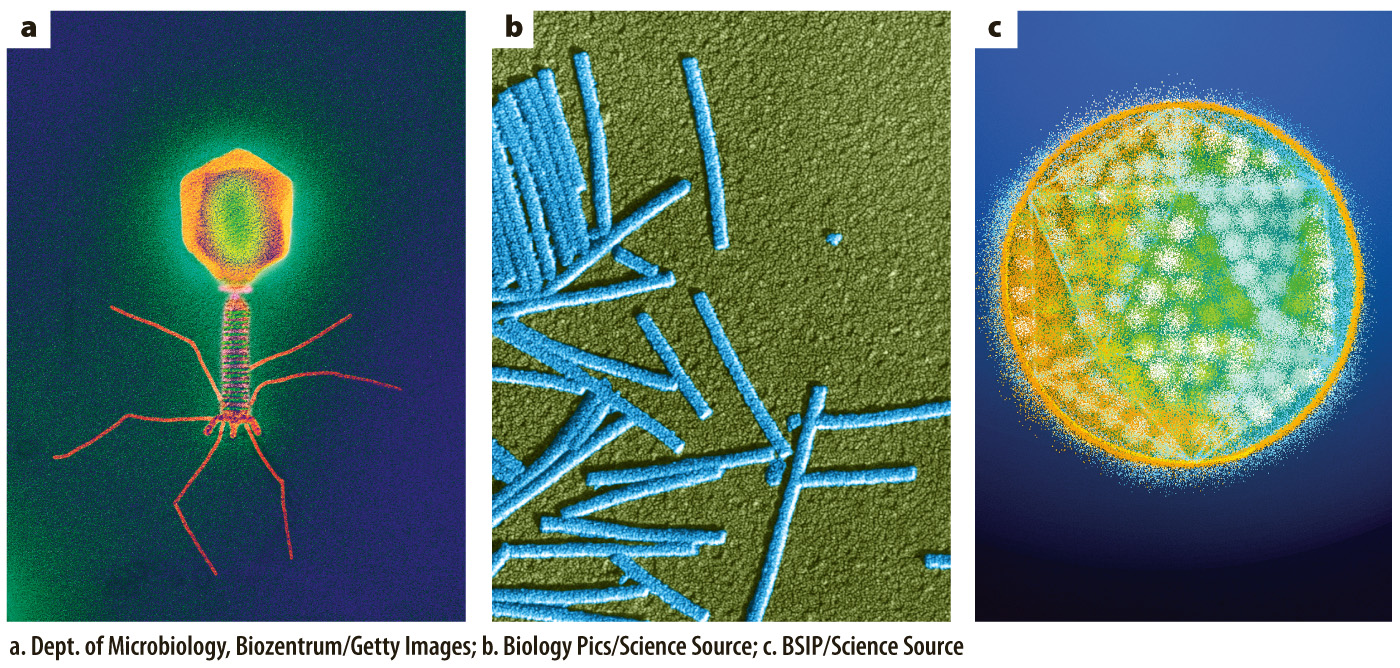

Viruses have diverse sizes and shapes.

Viruses show a wide variety of shapes and sizes, which are determined in some cases by the type of genome they carry. Three examples are shown in Fig. 13.18. The T4 virus (Fig. 13.18a) infects cells of the bacterium Escherichia coli. Viruses that infect bacterial cells are called bacteriophages, which literally means “bacteria eaters.” The T4 bacteriophage has a complex structure that includes a head composed of protein surrounding a molecule of double-

Most viruses are not structurally so complex. Consider the tobacco mosaic virus, which infects plants (see Fig. 13.17). It has a helical shape formed by the arrangement of protein subunits entwined with a molecule of single-

Many viruses have an approximately spherical shape formed from polygons of protein subunits that come together at their edges to form a polyhedral capsid. Among the most common polyhedral shapes is an icosahedron, which has 20 identical triangular faces. The example in Fig. 13.18c is adenovirus, a common cause of upper respiratory infections in humans. Many viruses that infect eukaryotic cells, such as adenovirus, are surrounded by a glycoprotein envelope composed of a lipid bilayer with embedded proteins and glycoproteins that recognize and attach to host cell receptors.