Genome annotation includes searching for sequence motifs.

Because genome annotation is essentially pattern recognition, it begins with the identification of patterns called sequence motifs, telltale sequences of nucleotides that indicate what types of function (or absence of function) may be encoded in a particular region of the genome (Fig. 13.4). Sequence motifs can be found in the DNA itself or in the RNA sequence inferred from the DNA sequence. Once identified, sequence motifs are typically confirmed by experimental methods. One sequence motif we have already encountered in Chapter 3 is a promoter, a sequence where RNA polymerase and associated proteins bind to the DNA to initiate transcription.

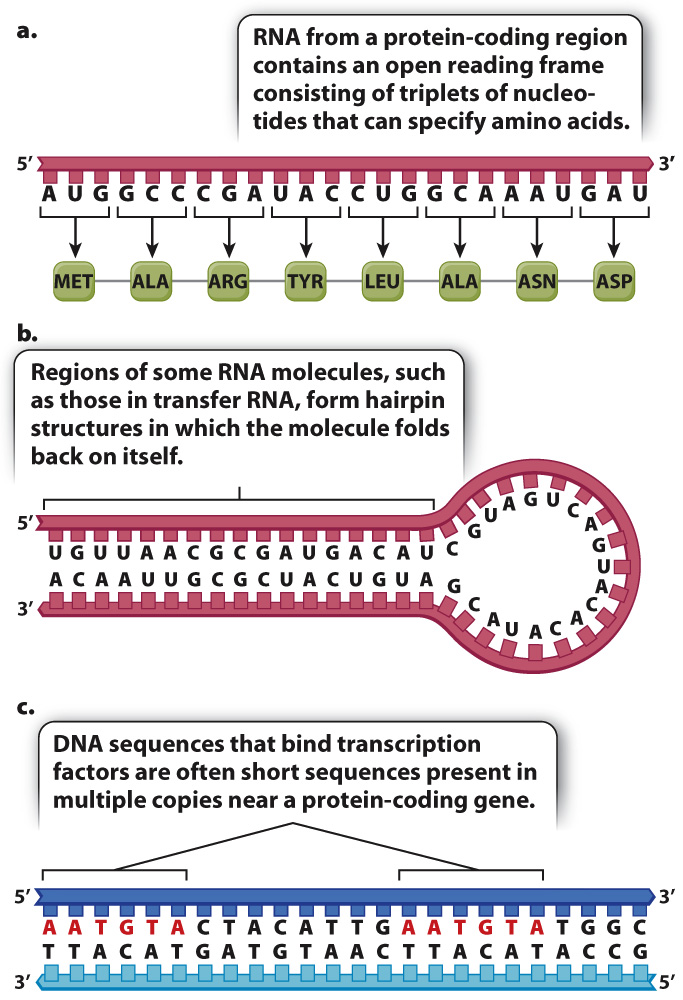

Another example of a sequence motif is an open reading frame (ORF) (Fig. 13.4a). The motif for an open reading frame is a long string of nucleotides that, if transcribed and processed into messenger RNA, would result in a set of codons for amino acids that does not contain a stop codon. The presence of an ORF motif by itself is enough to annotate the DNA segment as potentially protein coding. The qualifier “potentially” is necessary because ORFs identified in a DNA sequence do not necessarily code for protein. For this reason they are often called putative ORFs. A region containing a putative ORF may exist merely by chance (even a random sequence of nucleotides will contain ORFs averaging 21 codons in length); or a putative ORF may not be transcribed; or if a putative ORF is transcribed, it might be in a noncoding RNA or an intron of a protein-

Fig. 13.4b shows another type of sequence motif, this one also present in a hypothetical RNA transcript inferred from the DNA sequence. The nucleotide sequence at one end of the RNA is complementary to that at the other end, so the single-

Some sequence motifs are detected directly in the double-