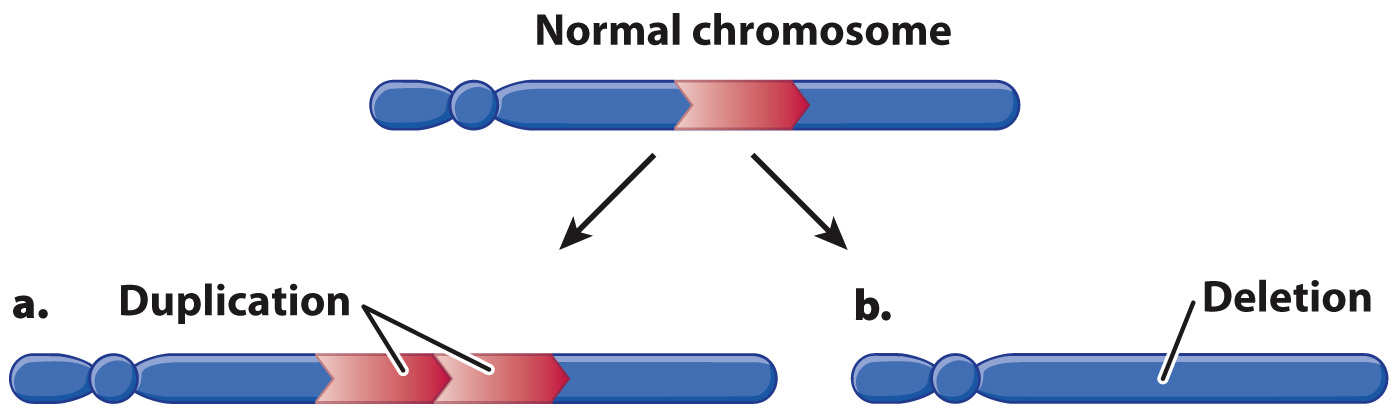

Duplications and deletions result in gain or loss of DNA.

Among the most common chromosomal abnormalities are those in which a segment of the chromosome is either present in two copies or is missing altogether (Fig. 14.12). A chromosome in which a region is present twice instead of once is said to contain a duplication (Fig. 14.12a). Although large duplications that include hundreds or thousands of genes are usually harmful and quickly eliminated from the population, small duplications including only one or a few genes can be maintained over many generations. Usually, duplication of a region of the genome is less harmful than deletion of the same region.

302

An example of a deletion, in which a region of the chromosome is missing, is shown in Fig. 14.12b. A deletion can result from an error in replication or from the joining of breaks in a chromosome that occur on either side of the deleted region. Even though a deletion may eliminate a gene that is essential for survival, the deletion can persist in the population because chromosomes usually occur in homologous pairs. If one member of a homologous pair has a deletion of an essential gene but the gene is present in the other member of the pair, that one copy of the gene is often sufficient for survival and reproduction. In these cases, the deletion can be transmitted from generation to generation and persist harmlessly, as long as the chromosome is present along with a normal chromosome.

But some deletions decrease the chance of survival or reproduction of an organism even when the homologous chromosome is normal. In general, the larger the deletion, the smaller the chance of survival. In the fruit fly Drosophila, individuals with deletions of more than 100–

It is worth emphasizing that one rarely observes deletions or duplications that include the centromere, the site associated with attachment of the spindle fibers that move the chromosome during cell division (Chapter 11). The reason is that an abnormal chromosome without a centromere, or one with two centromeres, is usually lost within a few cell divisions because it cannot be directed properly into the daughter cells during cell division.