Mutations are random with regard to an organism’s needs.

How do mutations arise? Consider the following example: If an antibiotic is added to a liquid culture of bacterial cells that are growing and dividing, most of the cells are killed, but a few survivors continue to grow and divide. These survivors are found to contain mutations that confer resistance to the antibiotic. This simple observation raises a profound question. Does this experiment reveal the presence of individual bacteria with mutations that had arisen spontaneously and were already present? Or do the antibiotic-

These alternative hypotheses have deep implications for all of biology because they suggest two very different ways in which mutations might arise. The first suggests that mutations occur without regard to the needs of an organism. According to this hypothesis, the presence of the antibiotic in the experiment with bacterial cells does not direct or induce antibiotic resistance in the cells, but instead allows the small number of preexisting antibiotic-

To distinguish between these two hypotheses, Joshua and Esther Lederberg in 1952 carried out a now-

Replica plating allowed the Lederbergs to isolate a pure culture of antibiotic-

Quick Check 1 If mutations occur at random with respect to an organism’s needs, how does a species become more adapted to its environment over time?

Quick Check 1 Answer

Mutant genes that are harmful or neutral are much less likely to persist in a population than ones that result in increased survival and reproduction because the latter mutations would lead to greater fitness.

296

HOW DO WE KNOW?

FIG. 14.5

Do mutations occur randomly, or are they directed by the environment?

BACKGROUND Researchers have long observed that beneficial mutations tend to persist in environments where they are useful—

HYPOTHESIS These observations lead to two hypotheses about how a mutation, such as one that confers antibiotic resistance on bacteria, might arise. The first suggests that mutations occur randomly in bacterial populations and over time become more common in the population in the presence of antibiotic (which destroys those bacteria without the mutation). In other words, they occur randomly with respect to the needs of an organism. The second hypothesis suggests that the environment, in this case the application of antibiotic, induces or directs antibiotic resistance.

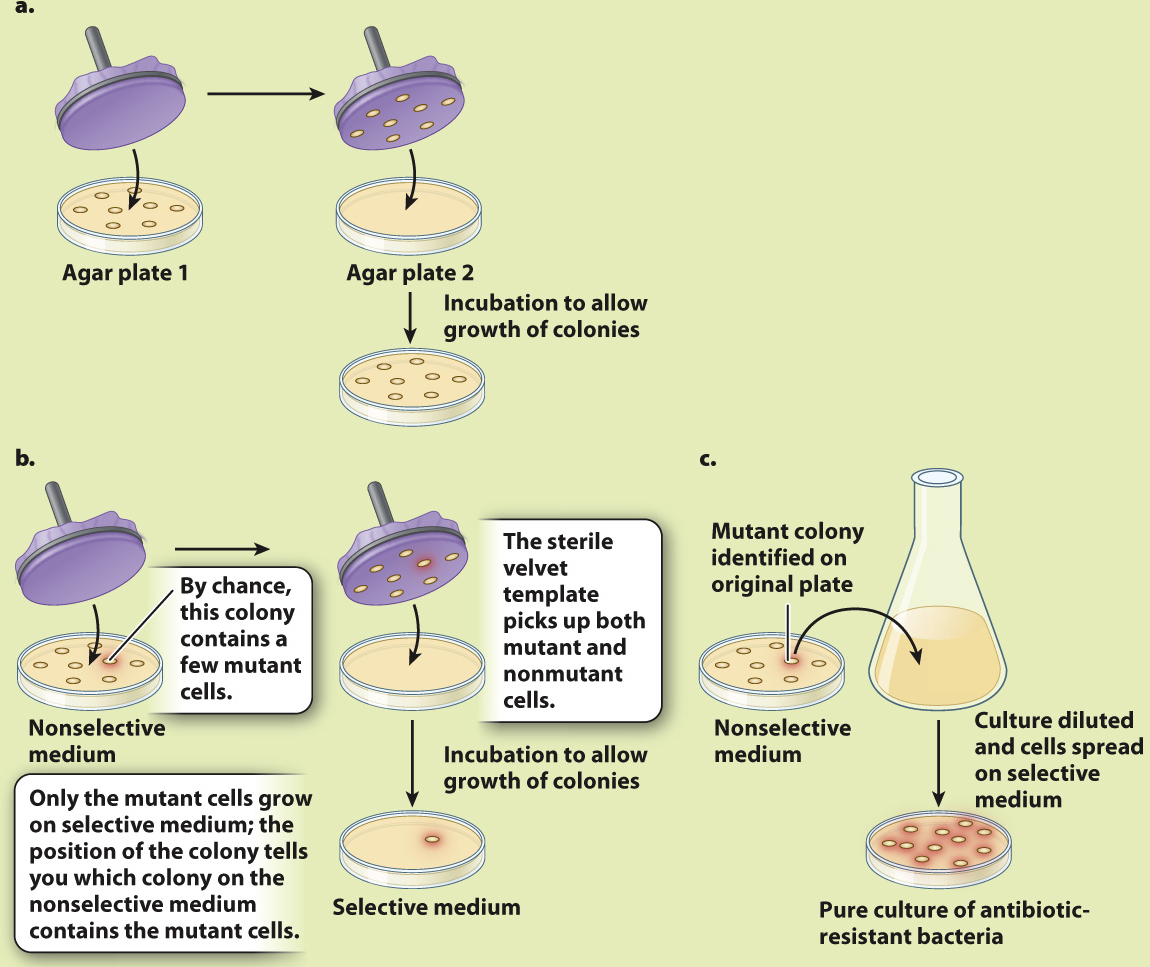

METHOD To distinguish between these two hypotheses, Joshua and Esther Lederberg developed replica plating. In this technique, bacteria are grown on agar plates, where they form colonies (Fig. 14.5a). The cells in any one colony result from the division of a single original cell, and thus they constitute a group of cells that are genetically identical except for rare mutations that occur in the course of growth and division. Then a disk of sterilized velvet is pressed onto the plate. Cells from each colony stick to the velvet disk (in mirror image, but the relative positions of the colonies are preserved). The disk is then pressed onto the surface of a fresh plate, transferring to the new plate a few cells that originate from each colony on the first agar plate, in their initial positions.

EXPERIMENT First, the Lederbergs grew bacterial colonies on medium without antibiotic, called a nonselective medium because all cells are able to grow and form colonies on it. Then, by replica plating, they transferred some cells from each colony to a plate containing antibiotic, so only antibiotic-

CONCLUSION The Lederbergs’ replica-

FOLLOW-

SOURCE Lederberg, J., and E. M. Lederberg. 1952. “Replica Plating and Indirect Selection of Bacterial Mutants.” Journal of Bacteriology 63:399–