Mendel’s experimental organism was the garden pea.

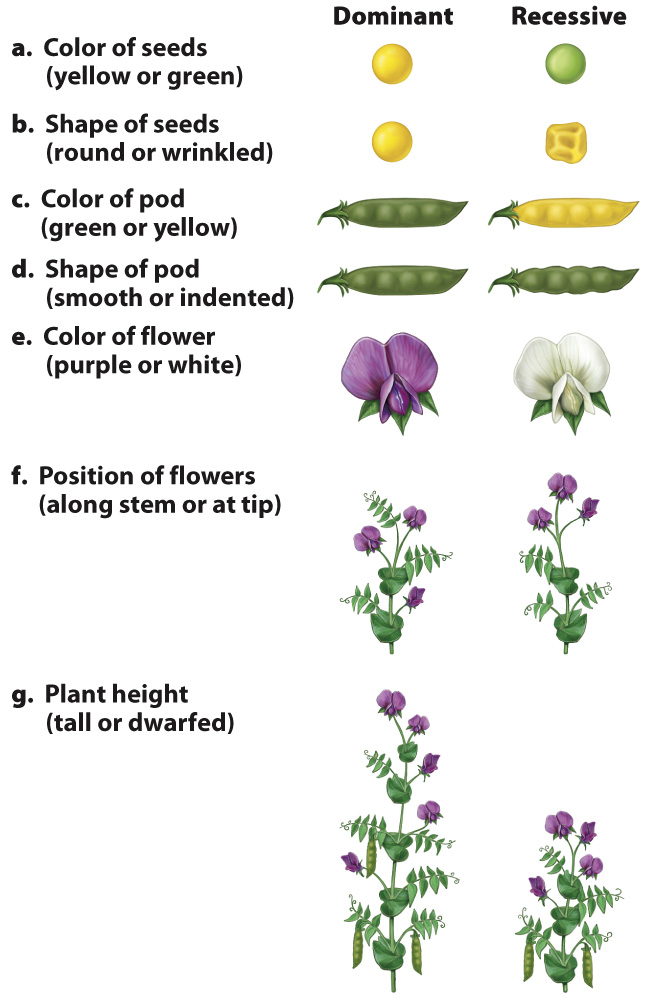

For his experimental material, Mendel used several strains of ordinary garden peas (Pisum sativum) that he obtained from local seed suppliers. His experimental approach was similar to that of a few botanists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries who studied the results of hybridization, or interbreeding between two different varieties or species of an organism. Where Mendel differed from his predecessors was in paying close attention to a small number of easily classified traits with contrasting characteristics. For example, where one strain of peas had yellow seeds, another had green seeds; and where one had round seeds, another had wrinkled seeds (Fig. 16.3). Altogether Mendel studied seven physical features expressed in contrasting fashion among the strains: seed color, seed shape, pod color, pod shape, flower color, flower position, and plant height.

The expression of each trait in each of the original strains that Mendel obtained was true breeding, which means that the physical appearance of the offspring in each successive generation is identical to the previous one. For example, plants of the strain with yellow seeds produced only yellow seeds, and those of the strain with green seeds produced only green seeds. Likewise, plants of the strain with round seeds produced only round seeds, and those of the strain with wrinkled seeds produced only wrinkled seeds.

The objective of Mendel’s experiments was simple. By means of crosses between the true-

In designing his experiments, Mendel departed from other plant hybridizers of the time in three important ways:

Mendel studied true-

breeding strains, unlike many other plant hybridizers, who used complex and poorly defined material. Mendel focused on one trait, or a small number of traits, at a time, with characteristics that were easily contrasted among the true-

breeding strains. Other plant hybridizers crossed strains differing in many traits and tried to follow all the traits at once. This resulted in amazingly complex inheritance, and no underlying patterns could be discerned. Mendel counted the progeny of his crosses, looking for statistical patterns in the offspring of his crosses. Others typically noted only whether offspring with a particular characteristic were present or absent, but did not keep track of and count all the progeny of a particular cross.