1.3 The Cell

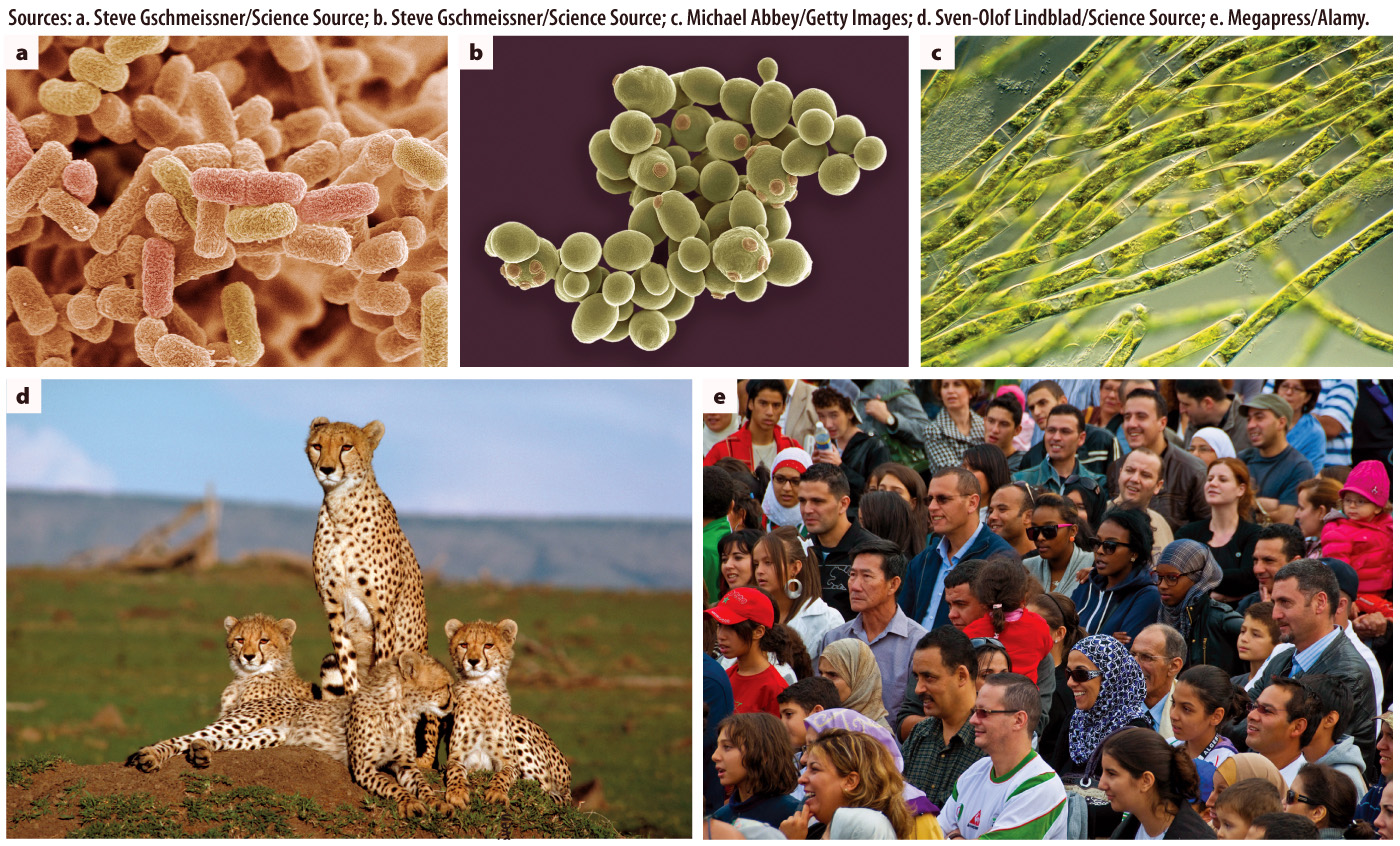

The cell is the simplest entity that can exist as an independent unit of life. Every known living organism is either a single cell or an ensemble of a few to many cells (Fig. 1.10). Most bacteria (like those in Pasteur’s experiment), yeasts, and the tiny algae that float in oceans and ponds spend their lives as single cells. In contrast, plants and animals contain billions to trillions of cells that function in a coordinated fashion.

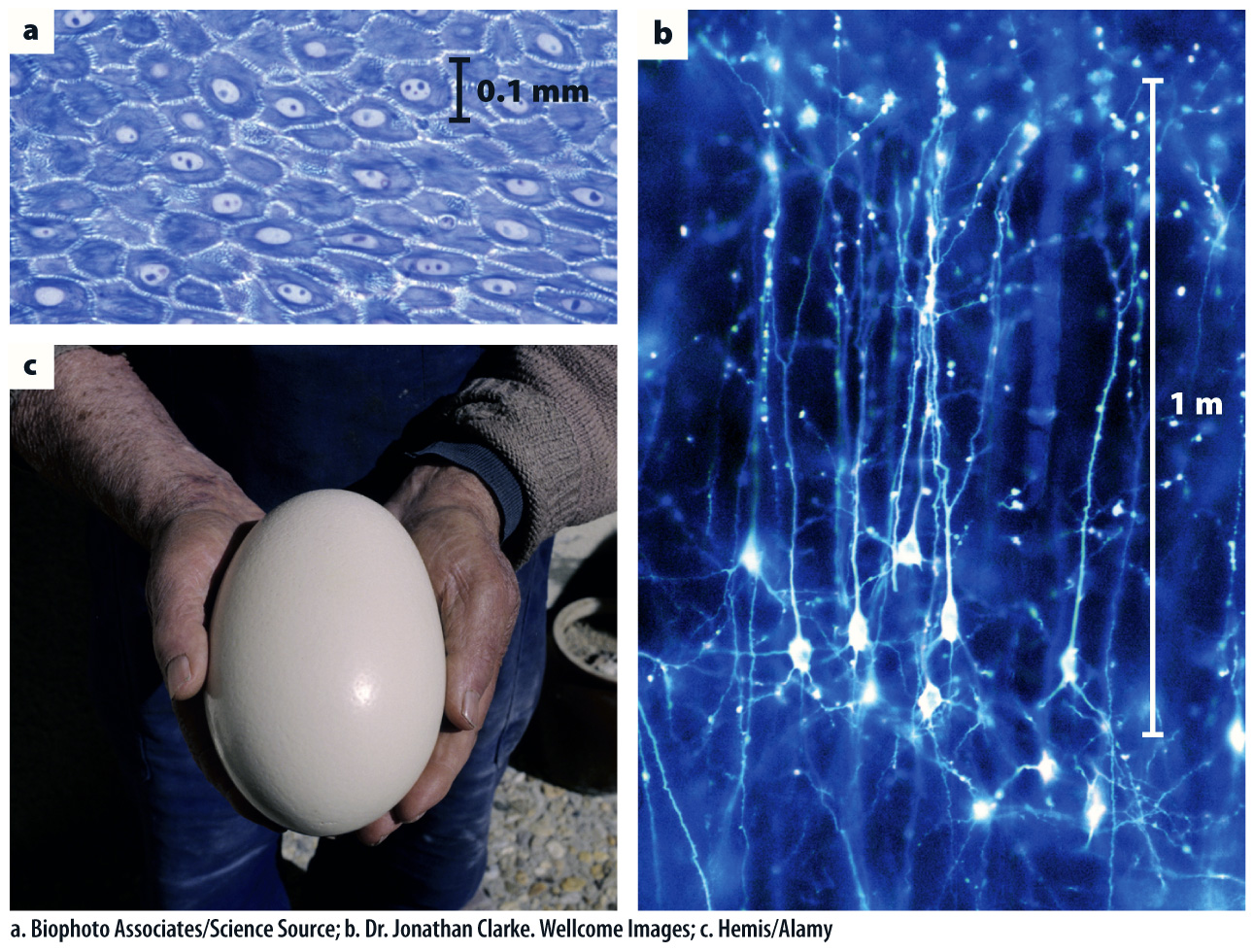

Most cells are tiny, their dimensions well below the threshold of detection by the naked eye (Fig. 1.11). The cells that make up the layers of your skin (Fig. 1.11a) average about 100 microns (μm) or 0.1 mm in diameter, which means that about 10 would fit in a row across the period at the end of this sentence. Many bacteria are less than a micron long. Certain specialized cells, however, can be quite large. Some nerve cells in humans, like the ones pictured in Fig. 1.11b, extend slender projections known as axons for distances as great as a meter, and the cannonball-

The types of cell just mentioned—