Case 2. Cancer: When Good Cells Go Bad

176

CASE 2

Imagine a simple vaccine that could prevent about 500,000 cases of cancer worldwide every year. You’d think such a discovery would be hailed as a miracle. Not quite. A vaccine to prevent cervical cancer, which affects about half a million women and kills as many as 275,000 annually, has been available since 2006. However, in the United States, this vaccine (and others) has stirred controversy.

Cancer is uncontrolled cell division. Cell division is a normal process that occurs during development of a multicellular organism and subsequently as part of the maintenance and repair of adult tissues. It is carefully regulated so that it occurs only at the right time and place. But sometimes, this careful regulation can be disrupted. When the normal checks on cell division become derailed, cancer can result.

When the normal checks on cell division become derailed, cancer can result.

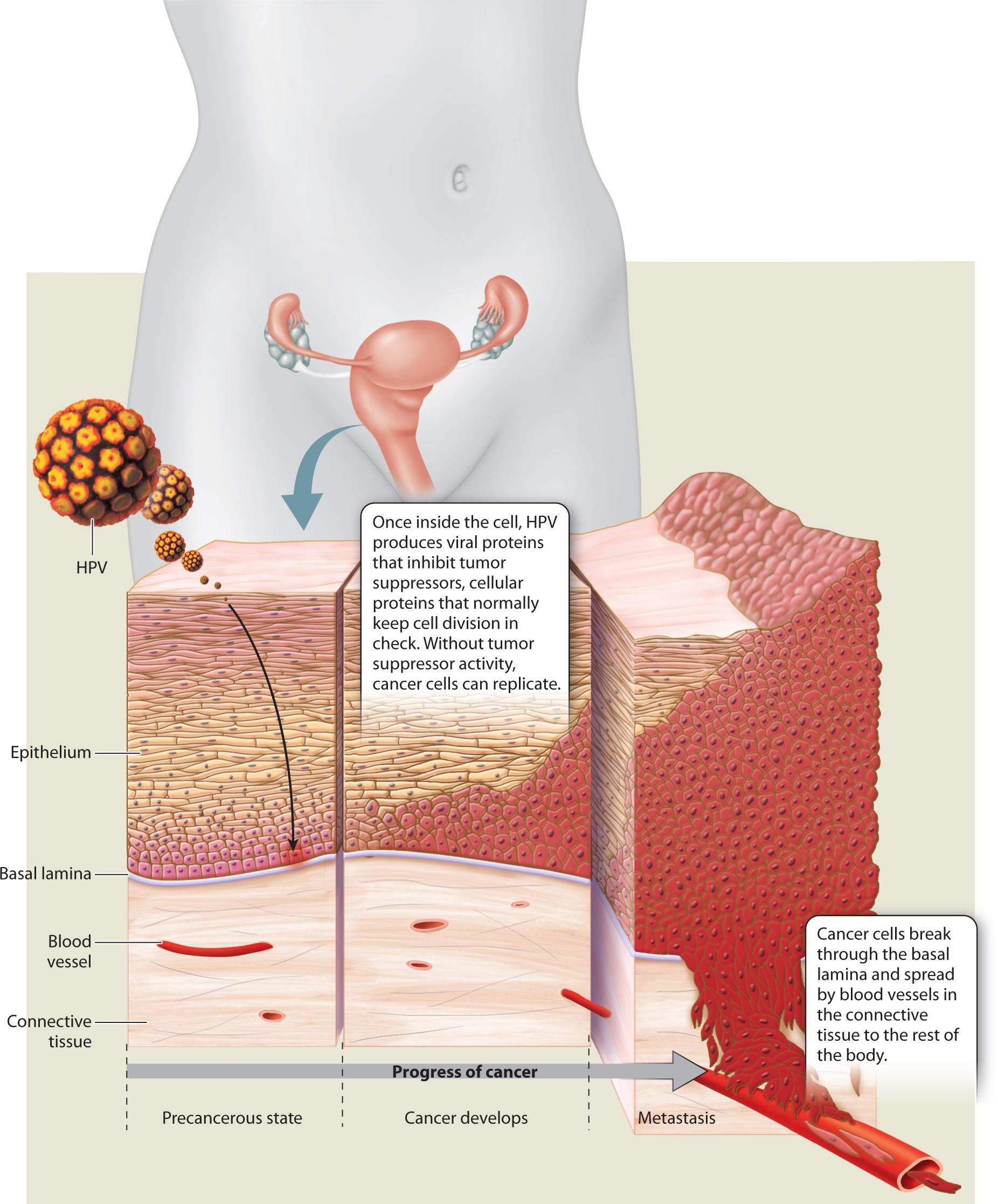

Most cancers are caused by inherited or acquired mutations, but some are caused by a virus. In fact, nearly all cases of cervical cancer are caused by a virus called human papillomavirus (HPV). There are hundreds of strains of HPV. Some of these strains cause minor problems such as common warts and plantar warts. Other strains are sexually transmitted. Some can cause genital warts but aren’t associated with cancer. However, a handful of “high-

HPV infects epithelial cells, a type of cell that lines the body cavities and covers the outer surface of the body. Once inside a cell, the virus hijacks the cellular machinery to produce new viruses. The high-

Once integrated into the DNA of human epithelial cells, two viral genes, E6 and E7, are expressed and produce two proteins. These viral proteins inhibit the products of key tumor suppressor genes. Tumor suppressor genes code for proteins called tumor suppressors that keep cell division in check by slowing down cell division, repairing DNA replication errors, or instructing defective cells to die. When tumor suppressors are prevented from doing these jobs, cancer can result.

HPV strikes in two ways. The viral E6 protein inhibits a protein called p53, an important tumor suppressor that, among other functions, prevents cell division in healthy cells when there is DNA damage. However, when bound by E6, p53 becomes essentially inactive. Meanwhile, the viral E7 protein inhibits a protein called Rb, which normally blocks transcription factors that promote cell division. Without Rb and p53 to put the brakes on cell division, cervical cells divide uncontrollably.

As they grow and multiply, the abnormal cells push through the basal lamina, a thin layer that separates the epithelial cells lining the cervix from the connective tissue beneath. Untreated, invasive cancer can spread to other organs. Once cancer travels beyond its primary location, the situation is grim. Most cancers cannot be cured after they have spread.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two vaccines for HPV, both of which protect against the high-

177

However, there are critics of these recommendations and mandates. Some say the government shouldn’t be making medical decisions. Others argue that the use of the vaccine condones sexual activity among young girls and boys. Still others have expressed concern over the vaccine’s safety.

178

Studies have found the HPV vaccine to be safe, a conclusion backed by a 2010 report from the Institute of Medicine, an independent nonprofit organization that advises the U.S government on issues of health. In spite of these findings, the HPV vaccine has not been widely accepted. The CDC found that by 2010, a full 5 years after the vaccine was introduced, only 32% of teenage girls had been fully vaccinated. In 2013, the percentage increased to 38%, but remained low.

Proponents of HPV vaccination say those numbers should cause concern. HPV is common: A 2007 study found that nearly 27% of American women ages 14–

Because cancer is often difficult to treat, especially in its later stages, many researchers focus on early detection or prevention. Early detection of cervical cancer can be accomplished by routine Pap smears, in which cells from the cervix are collected and observed under a microscope. As we have seen, cervical cancer is also an obvious target for prevention since it is caused by a virus that can be averted with a conventional vaccine. However, most cancers are not caused by viruses, and developing vaccines to prevent those cancers is a trickier proposition—

At the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, researchers are working to design vaccines to prevent breast and ovarian cancers from recurring in women who have been treated for these diseases. The researchers have zeroed in on proteins on the surface of cancerous cells. Cells communicate with one another by releasing signaling molecules that are picked up by receptor molecules on another cell’s surface, much the way a radio antenna picks up a signal. Cellular communication is critical for a functioning organism. Sometimes, though, the signaling process goes awry.

The Mayo Clinic team is focusing on two cell-

Even if these new therapies are successful, cancer researchers have much more work to do. Cancer is not one disease but many, and most of them are caused by a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors. Any number of things can go wrong as cells communicate, grow, and divide. But as researchers learn more about the cellular processes involved, they can step in to prevent or treat cancer. As the HPV vaccine shows, there is significant progress to be made.

CASE 2 QUESTIONS

Special sections in Chapters 9–

How do cell signaling errors lead to cancer? See page 192.

How do cancer cells spread throughout the body? See page 213.

What genes are involved in cancer? See page 236.