Case 5. The Human Microbiome: Diversity Within

525

CASE 5

Clostridium difficile doesn’t grab many headlines. Perhaps it should. This bacterium is thought to be the most common cause of hospital-

Now a promising (if stomach-

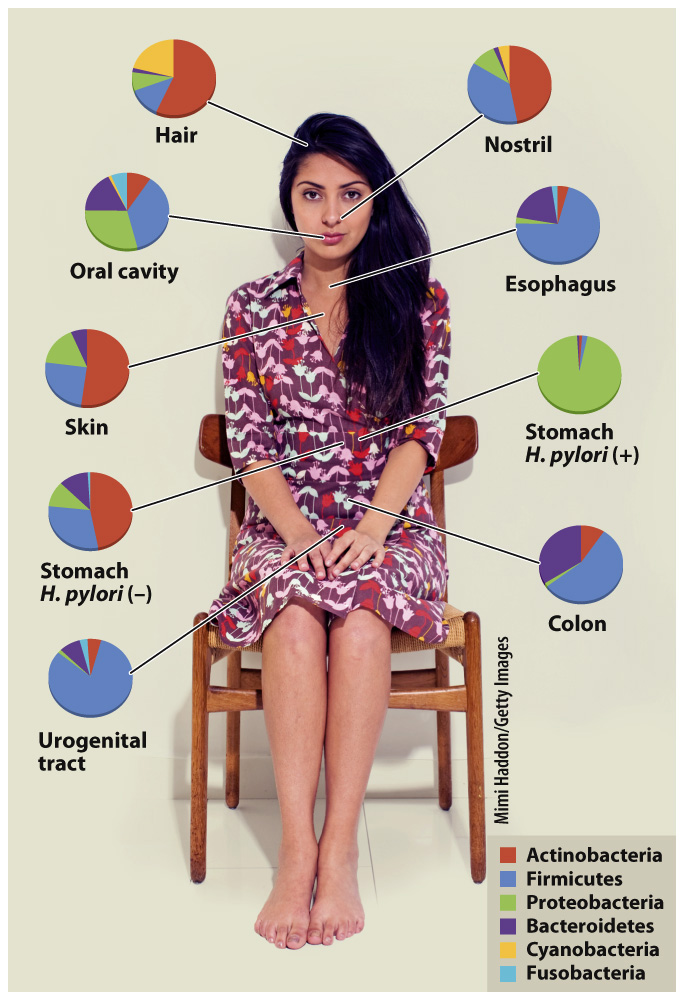

While transplanting fecal bacteria may not yet be mainstream medicine, there is no question that our gut, as well as our skin, mouth, nose, and urogenital tract, is home to a diversity of bacterial species. No one has yet identified all of the many microbes living on and within our bodies, but estimates suggest that each of us contains 10 times as many bacterial cells as human cells. For the most part, the relationship between “us and them” is a type of symbiosis, in which both humans and bacteria benefit from the close association. Indeed, the microbiome, as our assemblage of bacterial houseguests is known, affects human health in many important ways.

Some of the most mysterious, and most intriguing, members of our microbiome live in our gut. Bacteria living in our intestines help us break down food and synthesize vitamins. On the other hand, abnormal communities of microbes in the gut have been linked to Crohn’s disease, colon cancer, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Your own personal gut flora is a unique collection of species—

Despite these challenges, researchers have made strides toward understanding the unique bacterial communities within our intestinal tract. In 2011, scientists compared all the DNA sequences from gut microbes of people living in Europe, America, and Japan. They found that each individual fell into one of three enterotypes, or “gut types.” Most people had a bacterial mix dominated by organisms from the genus Ruminococcus. But others had gut types dominated by the genus Bacteroides or the genus Prevotella. The three different gut compositions appear to produce different vitamins and may even make a person more, or less, susceptible to certain diseases.

No one has yet identified the many microbes living on and within our bodies, but estimates suggest that each of us contains 10 times as many bacterial cells as human cells.

Surprisingly, the researchers reported that enterotype was unrelated to gender, body mass index, or nationality. So what determines your gut type? A follow-

The researchers don’t know yet what a person’s enterotype means for his or her health. But scientists are eager to explore the link between microbiome and physical well-

As it happens, there are good reasons to peer into a cow’s gut. The cow’s rumen (one of its four digestive chambers) contains microbes that break down the cellulose in plant material. Without them, cattle wouldn’t be able to extract adequate nutrition from the grass they graze. Those microbes are the particular focus of scientists at the Department of Energy (DOE), who are interested in converting material containing cellulose, such as switchgrass, into biofuels.

526

As researchers look for more sustainable replacements for fossil fuels, many have pinned their hopes on biofuels. But the enzymes currently used commercially to break down cellulose aren’t efficient or cost effective enough to produce biofuels on an industrial scale. That’s where the cows come in. DOE scientists recently analyzed the microbial genes present in the cow rumen. They discovered nearly 28,000 genes for proteins that metabolize carbohydrates, and at least 50 new proteins. The hope is that some of these newly discovered proteins will help break down cellulose in ways that will produce biofuels more efficiently and cheaply.

527

Mammals such as cows and humans are hardly the only organisms that have symbiotic relationships with bacteria. All living animals have their own microbiomes. Even tiny single-

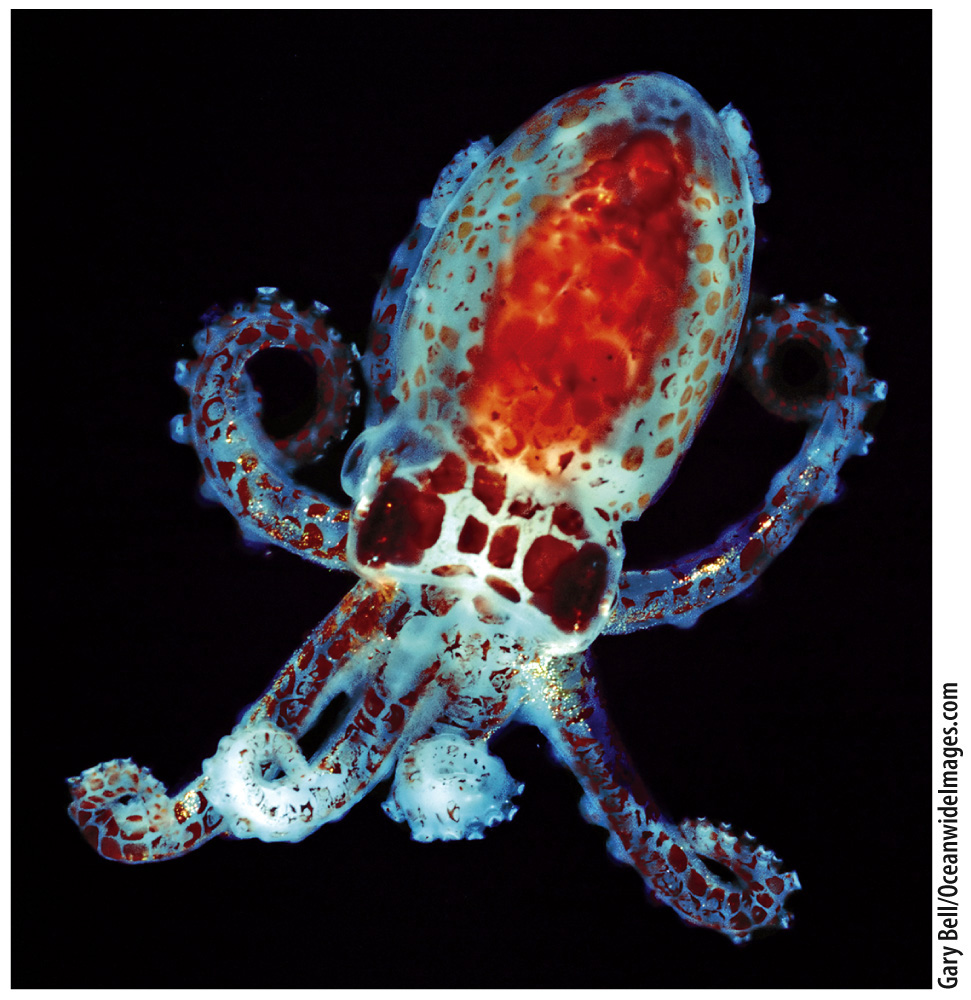

Symbiotic bacteria provide a variety of benefits to their hosts. Consider the bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes, which possesses a specialized organ to house bacteria. The bacteria, Vibrio fischeri, are luminescent—

In many cases, animals and their bacterial symbionts are so intimately connected that it’s hard to separate one from the other. Many human gut bacteria are poorly studied because scientists haven’t been able to grow them outside the body. But some species have taken their intimate bacterial partnership a step further.

Aphids are small insects that feed on plant sap. They rely on the bacterium Buchnera aphidicola to synthesize certain amino acids for them that aren’t available from their plant-

528

Clearly, there are many good reasons to learn more about our bacterial comrades. From evolution to energy to human health, our microbiomes hold great promise—

CASE 5 QUESTIONS

Special sections in Chapters 26 and 27 discuss the following questions related to Case 5.

How do intestinal bacteria influence human health? See page 550.

What role did symbiosis play in the origin of chloroplasts? See page 557.

What role did symbiosis play in the origin of mitochondria? See page 559.

How did the eukaryotic cell originate? See page 560.