Case 8. Biodiversity Hotspots: Rain Forests and Coral Reefs

941

CASE 8

When we think about mass extinctions, the demise of the dinosaurs is often the first example to spring to mind. But many conservationists believe we are in the midst of a mass extinction today. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature has estimated that 800 plant and animal species in habitats around the world have died out in the last 500 years, and more than 16,000 are currently at risk of extinction.

The cause of this die-

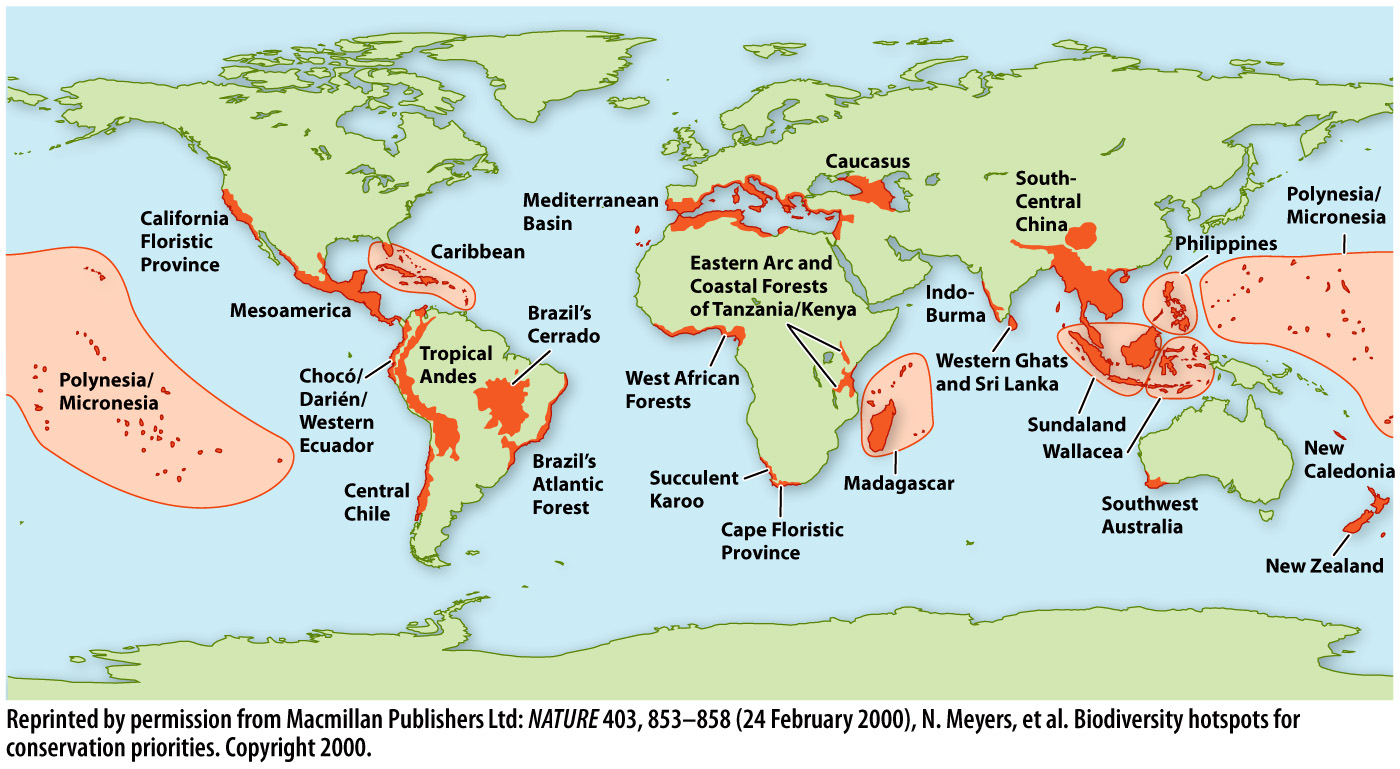

It’s clearly not possible to save every single species threatened with extinction. Conservationists must make difficult choices, prioritizing which species to protect. To get the most bang for every conservation buck, ecologists have identified 25 priority areas, or biodiversity hotspots.

These hotspots are areas with disproportionately large concentrations of endemic species—

The islands of the Caribbean—

Hispaniola is only about the size of Ireland, yet it contains a striking assortment of habitats, including desert, savanna, rain forests, dry forests, pine forests, coastal estuaries, and interior mountains. With such a rich abundance of habitats, Hispaniola is, in some ways, a microcosm of the planet’s many ecosystems. And like the Earth’s other natural places, Hispaniola faces many challenges to its native biological diversity.

Of all the habitats on Hispaniola, the forests have the greatest variety of plants, animals, and other organisms. Ferns, orchids, and bromeliads—

The forest is alive with activity. Ants march silently. Crickets and cicadas buzz and whine in the treetops. Vertebrate vocalists such as frogs and birds fill the air with chirps and whistles, making themselves known to both potential mates and rivals. Bats swoop through the darkened skies, using ultrasonic calls to locate insect prey. About 30,000 species of multicellular organisms are found on Hispaniola, and a third of those are endemic—

Conservationists must make difficult choices, prioritizing which species to protect. To get the most bang for every conservation buck, ecologists have identified 25 priority areas, or biodiversity hotspots.

How did all these species come to live on the island? Over tens of millions of years, organisms traveled to Hispaniola by air and by sea. Geographically separated from their ancestors on the mainland, many of these organisms evolved to become distinct species. As they adapted to fill vacant niches on the island, animals such as Anolis lizards, frogs, and crickets evolved an impressive diversity of forms.

In some cases, scientists have been able to explore Hispaniola’s evolutionary history directly. They have found remains of insects and other species entombed in fossilized tree resin, or amber, 30–

942

The stunning diversity of Hispaniola doesn’t exist just on land. Conservationists consider the warm, shallow reefs of the Caribbean one of the world’s marine biodiversity hotspots. Coral reefs in general are among the world’s most biologically diverse ecosystems. Species from all recognized phyla of animals are found on reefs.

Around the world, reefs support many thousands of species, including snails, corals, lobsters, and fish. Many, but not all, of these creatures spend their entire life in this habitat. Reefs also act as vital nursery grounds for animals that live in other parts of the ocean, from sea turtles to sharks. Reef biodiversity is critical to maintaining fisheries that provide food and income for millions of people.

Hispaniola’s rain forests and reefs—

Reefs around the world are being damaged by human activities. Overfishing and pollution take their toll on reef ecosystems. Climate change is increasing seawater temperature and increasing CO2 is altering ocean chemistry. Those changes are threatening the coral organisms that form the backbone of the reefs.

Ecosystems on land, too, face significant challenges. The Caribbean islands retain only about 11% of their original vegetation. Humans have cleared great swaths of land for agriculture and chopped trees to use as fuel. Humans have also introduced non-

If Hispaniola serves as a microcosm of the planet’s ecosystems, it also serves as a cautionary tale. Two divergent paths have emerged on the single island. Haiti has historically suffered greater poverty than the Dominican Republic, and has much greater population density. Those factors put more pressure on the environment in Haiti, and have contributed to much greater deforestation on the western half of the island.

The case of Hispaniola illustrates the complex challenges facing conservationists. Solutions to environmental challenges must take into consideration the effects of poverty, culture, and other social pressures. Balancing the needs of humans with the needs of natural ecosystems is no easy task. But as a relatively small island, Hispaniola may in fact be in a better position to turn things around than larger, more politically complex countries. The world’s biodiversity hotspots might yet lead the charge in finding ways for humans and the rest of the planet’s inhabitants to coexist peacefully.

943

CASE 8 QUESTIONS

Special sections in Chapters 44–

How have reefs changed through time? See page 975.

How do islands promote species diversification? See page 1019.

Can competition drive species diversification? See page 1025.

How is biodiversity measured? See page 1032.

Why does biodiversity decrease from the equator toward the poles? See page 1066.

How has global environmental change affected coral reefs around the world? See page 1077.

What are our conservation priorities? See page 1091.