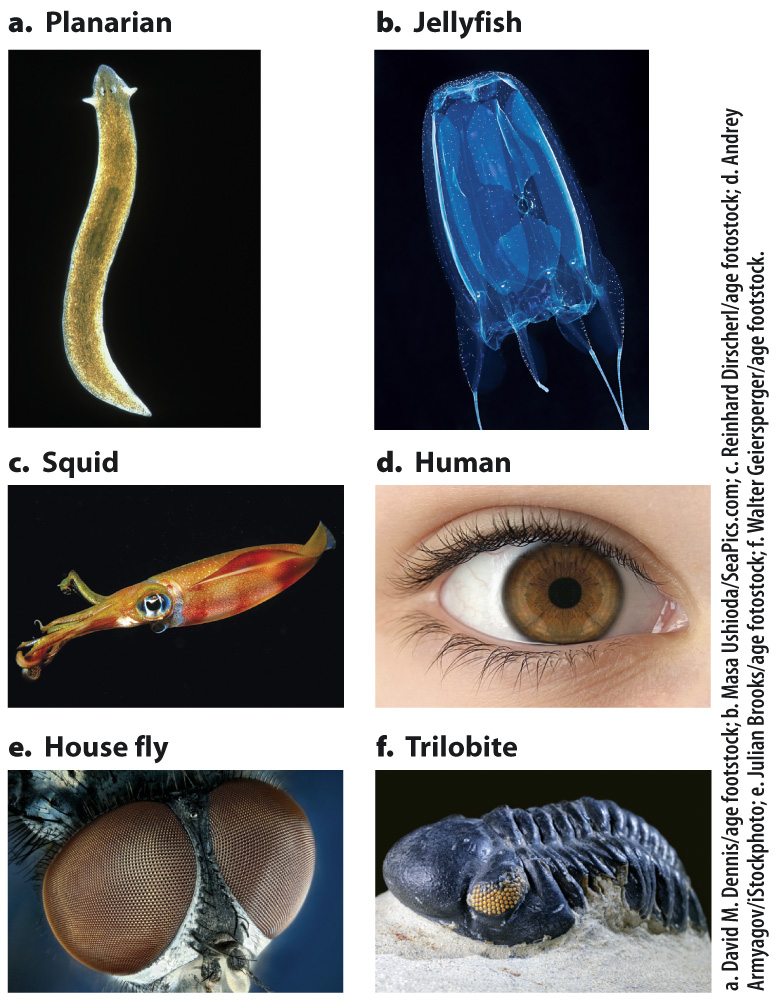

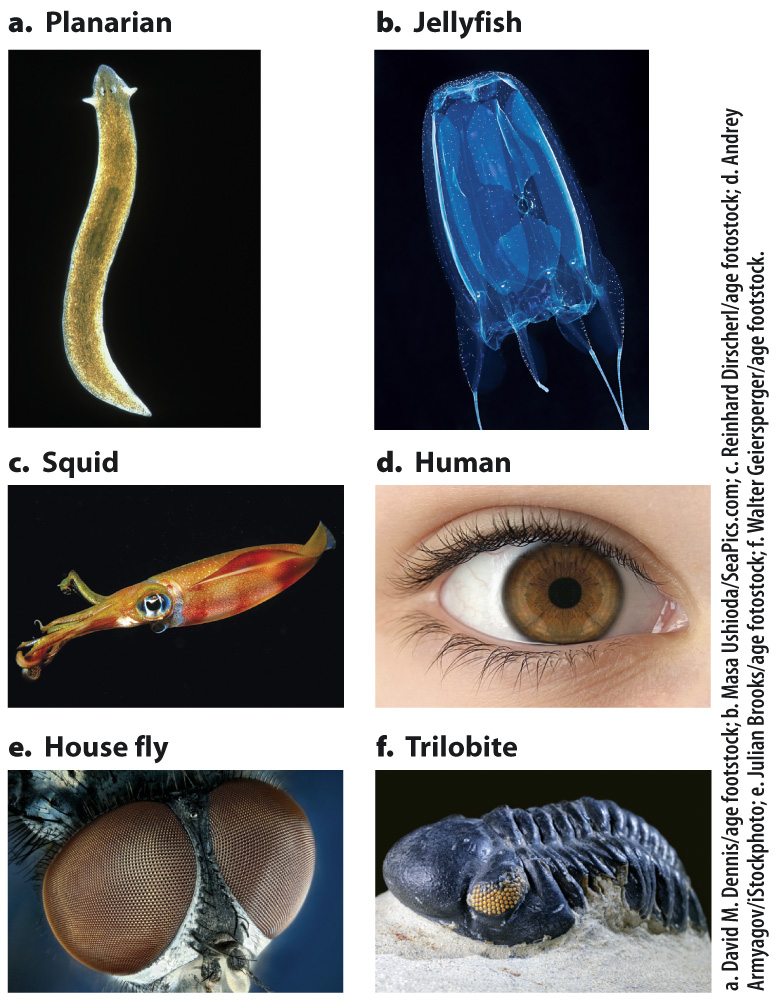

Animals have evolved a wide variety of eyes.

FIG. 20.16 Diversity of animal eyes.

Animal eyes show an amazing diversity in their development and anatomy (Fig. 20.16). Among the simplest eyes are those of the planarian flatworm (Fig. 20.16a), which are only pit-shaped cells containing light-sensitive photoreceptors. The planarian eye has no lens to focus the light, but the animal can perceive differences in light intensity. The incorporation of a spherical lens, as in some jellyfish (Fig. 20.16b), improves the image.

Among the most complex eyes are the camera-type eyes of the squid (Fig. 20.16c) and human (Fig. 20.16d), which have a single lens to focus light onto a light-sensitive tissue, the retina (Chapter 36). Though the single-lens eyes of squids and vertebrates are similar in external appearance, they are vastly different in their development, anatomy, and physiology.

Some organisms, such as the house fly (Fig. 20.16e) and other insects, have compound eyes, that is, eyes consisting of hundreds of small lenses arranged on a convex surface pointing in slightly different directions. This arrangement of lenses allows a wide viewing angle and detection of rapid movement.

In the history of life, eyes are very ancient. By the time of the extraordinary diversification of animals 542 million years ago known as the Cambrian explosion, organisms such as trilobites (Fig. 20.16f) already had well-formed compound eyes. These differed greatly from the eyes in modern insects, however. For example, trilobite eyes had hard mineral lenses composed of calcium carbonate (the world’s first safety glasses, so to speak). Altogether, about 96% of living animal species have true eyes that produce an image, as opposed to simply being able to detect differences in light intensity. Despite this common feature, the extensive diversity among the eyes of different organisms encouraged evolutionary biologists in the belief that the ability to perceive light may have evolved independently about 40 to 60 times.