The fertilized egg is a totipotent cell.

In all sexually reproducing organisms, the fertilized egg is special because of its developmental potential. The fertilized egg is said to be totipotent, which means that it can give rise to a complete organism. In mammals, the egg also forms the membranes that surround and support the developing embryo (Chapter 42).

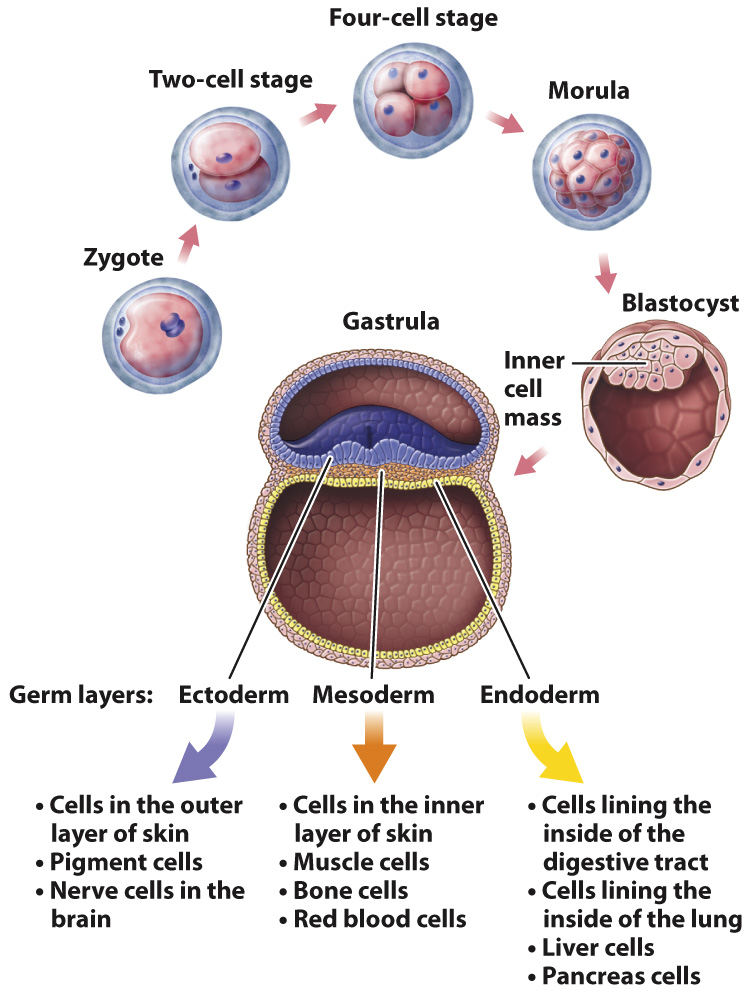

After fertilization, the fertilized egg, or zygote, undergoes successive mitotic cell divisions as it moves along a fallopian tube. One cell becomes two, two become four, four become eight, eight become sixteen, and so on, with all the cells contained within the egg’s outer membrane (Fig. 20.1). Within 4–

401

These early cell divisions are different from the mitotic cell divisions that occur later in life because the cells do not grow between divisions; they merely replicate their chromosomes and divide again. The result is that the cytoplasm of the egg is partitioned into smaller and smaller packages, with the new cells all bunched together inside the membrane that covers the developing embryo.

Cell division continues in the morula until there are a few thousand cells. The cells then begin to move relative to one another, pushing against and expanding the membrane that encloses them and rearranging themselves to form a hollow sphere called a blastocyst (Fig. 20.1). In one region of the inner wall of the blastocyst, there is a group of cells known as the inner cell mass, from which the body of the embryo develops. The wall of the blastocyst forms several membranes that envelop and support the developing embryo. Once the blastocyst forms, it implants in the uterine wall.

Once implanted in the uterine wall, the multiplying cells of the inner cell mass reorganize to form a gastrula, in which the blastula becomes organized into three germ layers (Fig. 20.1). Germ layers are sheets of cells that include the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm and that differentiate further into specialized cells. Those formed from the ectoderm include the outer layer of the skin and nerve cells in the brain; cells from the mesoderm include cells that make up the inner layer of the skin, muscle cells, and red blood cells; and cells formed from the endoderm include cells of the lining of the digestive tract and lung, as well as liver cells and pancreas cells (Chapter 42).