Natural selection brings about adaptations.

The adaptations we see in the natural world—

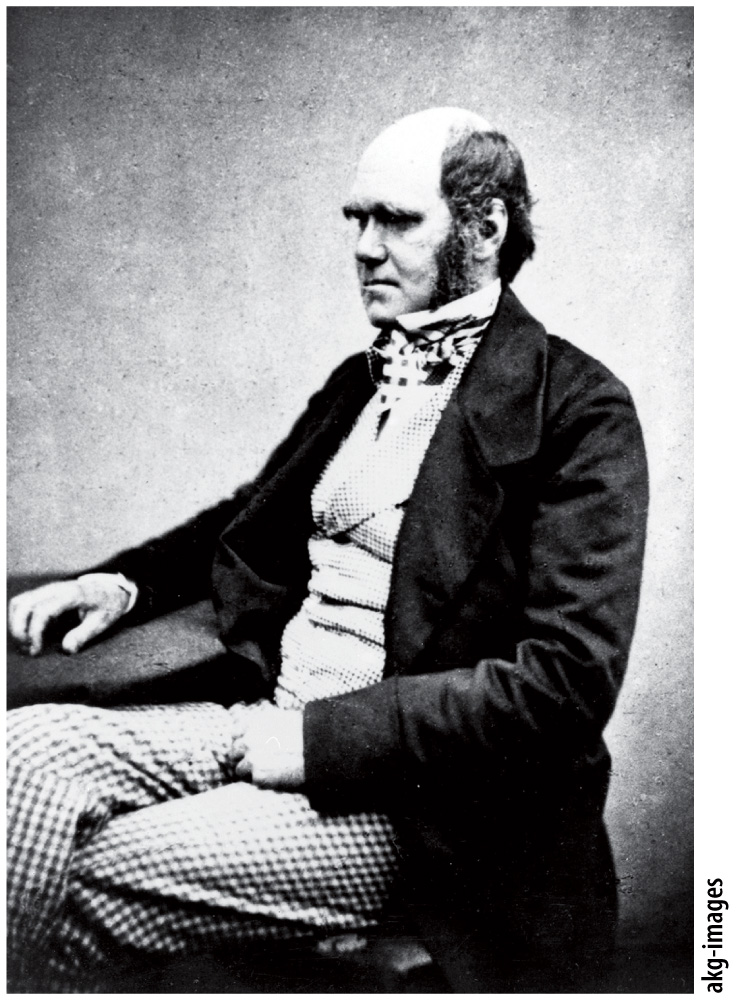

With the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859, Darwin, pictured in Fig. 21.6, overturned the biological convention of his day on two fronts. First, he showed that species are not unchanging; they have evolved over time. Second, he suggested a mechanism, natural selection, that brings about adaptation. Natural selection was a brilliant solution to the central problem of biology: how organisms come to fit so well in their environments. From where does the woodpecker get its powerful chisel of a bill? And the hummingbird its long delicate bill for probing the nectar stores in flowers? Darwin showed how a simple mechanism, without foresight or intentionality, could result in the extraordinary range of adaptations that all of life is testimony to.

433

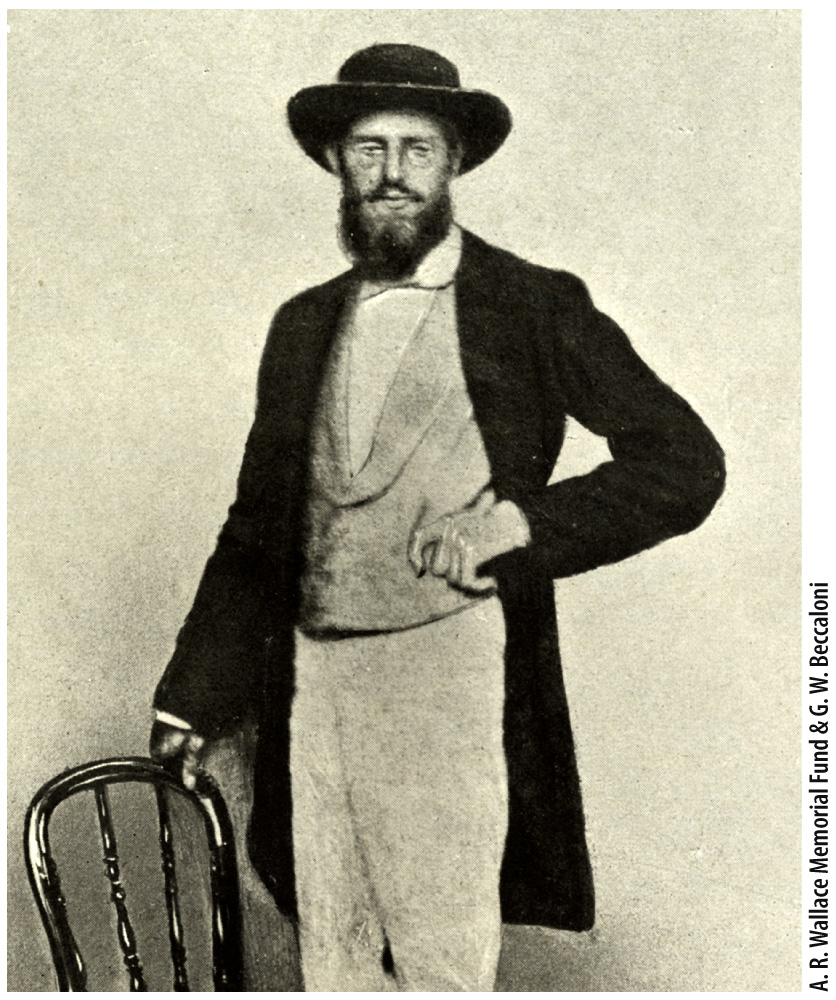

For 20 years after first conceiving the essence of his theory, Darwin collected supporting evidence. In 1858, however, he was spurred to begin writing On the Origin of Species by a letter from a little-

Suddenly, Darwin was confronted with the prospect of losing his claim on the theory that he had been quietly nurturing for 20 years. But all was not lost. Darwin’s colleagues arranged for the publication of a joint paper by Wallace and Darwin in 1858. This was done without consulting Wallace, who nonetheless never resented Darwin and afterward was careful to insist that the idea rightly belonged to the older man. It was Darwin’s publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859 that brought both evolution and natural selection, its underlying mechanism of adaptation, to public attention. Wallace is only fleetingly mentioned in Darwin’s great work, and Darwin, not Wallace, is now the name associated with the discovery.

Both Darwin and Wallace recognized their debt to the writings of a British clergyman, Thomas Malthus. In his Essay on the Principle of Population, first published in 1798, Malthus pointed out that natural populations have the potential to increase in size geometrically, meaning that populations get larger at an ever-

However, this geometric expansion of populations does not occur. In fact, population sizes are typically stable from generation to generation. This is because the resources upon which populations are dependent—

Which individuals will win the competition? Darwin and Wallace suggested that those that are best adapted would most likely survive and leave more offspring. Genetic variation among individuals results in some that are more likely than others to survive and reproduce, passing their genetic material to the next generation. As a result, the next generation will have a higher proportion of these same advantageous alleles. Darwin used the term “natural selection” for the filtering process that acts against deleterious alleles and in favor of advantageous ones.

Competitive advantage is a function of how well an organism is adapted to its environment. A desert plant that is more efficient at minimizing water loss than another plant is better adapted to the desert environment. An organism that is better adapted to its environment is more fit. Fitness, in this context, is a measure of the extent to which the individual’s genotype is represented in the next generation. We say that the first plant’s fitness is higher than the second’s if it leaves more surviving offspring either because the plant itself survives for longer, giving it greater opportunity to reproduce, or because it has some other reproductive advantage, such as the ability to produce more seeds. Assuming that the trait maintains its advantage, natural selection then acts over generations to increase the overall fitness of a population. A plant population newly arrived in a desert may be poorly adapted to its environment, but, over time, alleles that minimize water loss increase under natural selection, resulting in a population that is better adapted to the desert.

Such changes in populations take time. Borrowing from the geologists of his day, Darwin recognized that time was a critical ingredient of his theory. Geologists had put forward a view of Earth’s history that argued that large geological changes—

434