21.6 Molecular Evolution

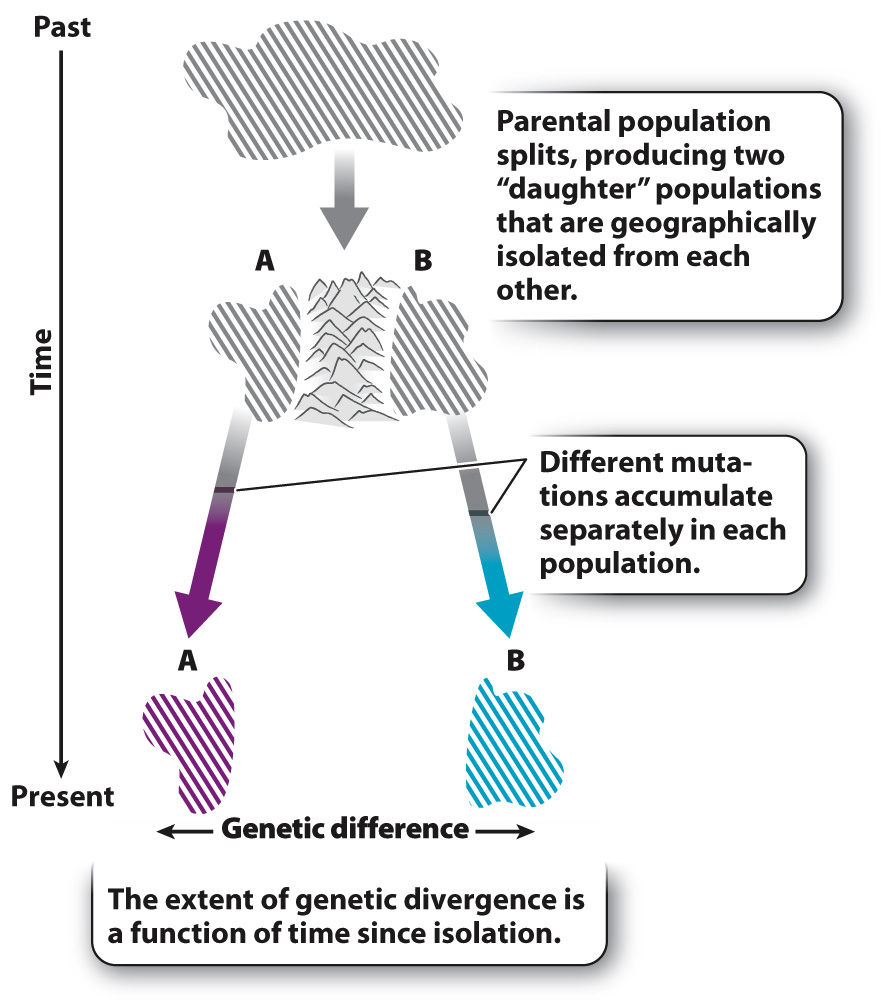

How do DNA sequence differences arise among species? Imagine starting with two pairs of identical twins, one pair male and the other female. Now we place one member of each pair together on either side of a mountain range (Fig. 21.14). Let’s assume the mountain range completely isolates each couple. What, in genetic terms, will happen over time? The original pairs will found populations on each side of the mountain range. The genetic starting point, in each case, is exactly the same, but, over time, differences will accumulate between the two populations. Mutations will occur in one population that will not have arisen in the other population, and vice versa.

A mutation in either population has one of three fates: It goes to fixation (either through genetic drift or through positive selection); it is maintained at intermediate frequencies (by balancing selection); or it is eliminated (either through natural selection or genetic drift). Different mutations will be fixed in each population. When we come back thousands of generations later and sequence the DNA of our original identical individuals’ descendants, we will find that many differences have accumulated. The populations have diverged genetically. What we are seeing is evidence of molecular evolution.

Species are the biological equivalents of islands because they, too, are isolated. They are genetically isolated because, by definition, members of one species cannot exchange genetic material with members of another (Chapter 22). The amount of time that two species have been isolated from each other is the time since their most recent common ancestor. Thus, humans and chimpanzees, whose most recent common ancestor lived about 6–