Speciation is a by-

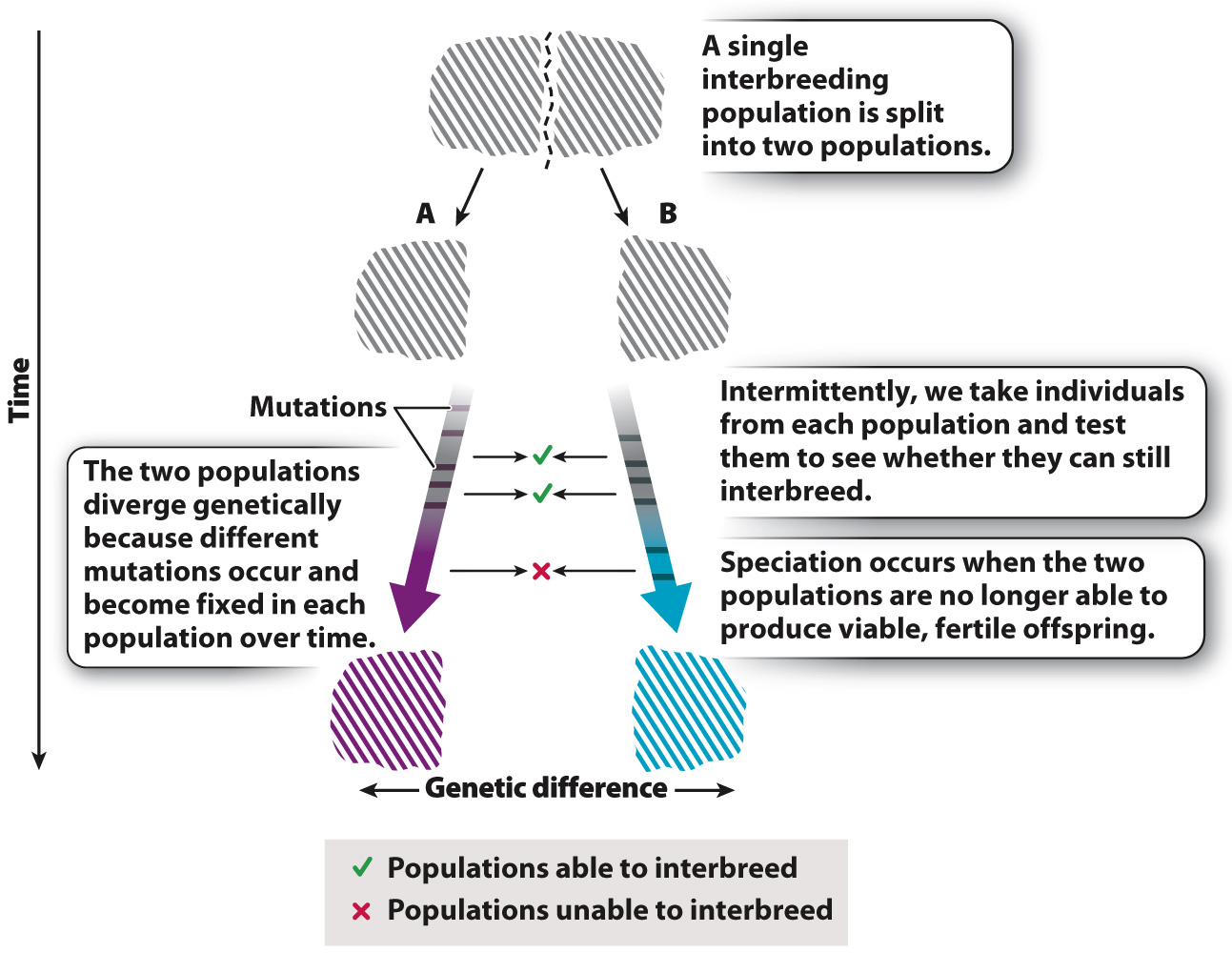

The key to speciation is the fundamental evolutionary process of genetic divergence between genetically separated populations. As we saw in Chapter 21, if a single population is split into two populations that are unable to interbreed, different mutations will appear by chance in the two populations. Like all mutations, these will be subject to genetic drift or natural selection (or both), resulting over time in the genetic divergence of the two populations. Two separate populations that are initially identical will, over long periods of time, gradually become distinct as different mutations are introduced and propagated in each population. At some stage in the course of divergence, changes occur in one population that lead to its members’ being reproductively isolated from members of the other population (Fig. 22.6). It is this process that results in speciation.

Speciation—

As Fig. 22.6 shows, speciation is typically a gradual process. If we try to cross members of two populations that have genetically diverged but not diverged far enough for full reproductive isolation (that is, speciation) to have arisen, we may find that the populations are partially reproductively isolated. They are not yet separate species, but the genetic differences between them are extensive enough that the hybrid offspring they produce have reduced fertility or viability compared to offspring produced by crosses between individuals within each population.