Co-speciation is speciation that occurs in response to speciation in another species.

As we have seen, physical separation is often a critical ingredient in speciation. Two populations that are not fully separated from each other—that is, there is gene flow between them—will typically not diverge from each other genetically, because genetic exchange homogenizes them. This is why most speciation is allopatric. Allopatric speciation brings to mind populations separated from each other by stretches of ocean or deserts or mountain ranges. However, separation can be just as complete even in the absence of geographic barriers.

Consider an organism that parasitizes a single host species. Suppose that the host undergoes speciation, producing two daughter species. The original parasite population will also be split into two populations, one for each host species. Thus, the two new parasite populations are physically separated from each other and will diverge genetically, ultimately undergoing speciation. This divergence results in a pattern of coordinated host–parasite speciation called co-speciation, a process in which two groups of organisms speciate in response to each other and at the same time.

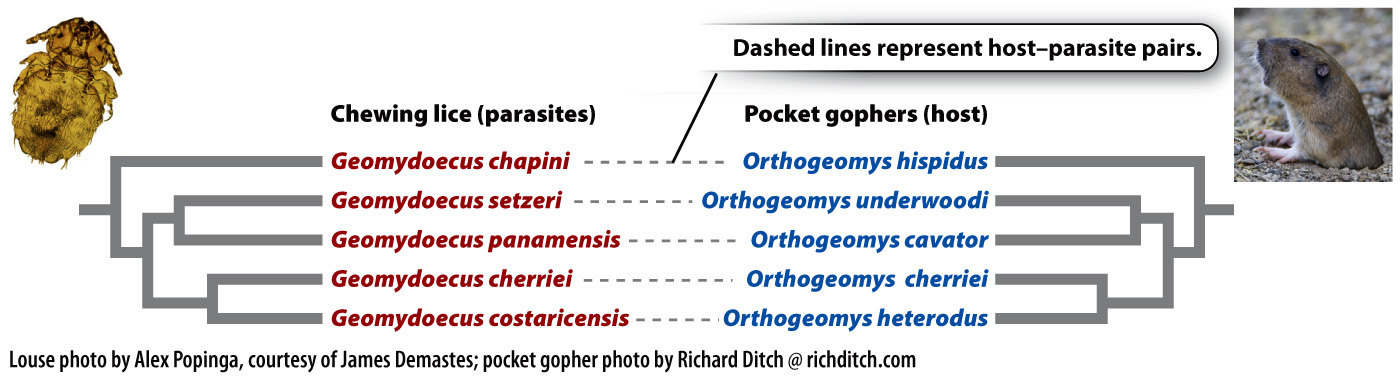

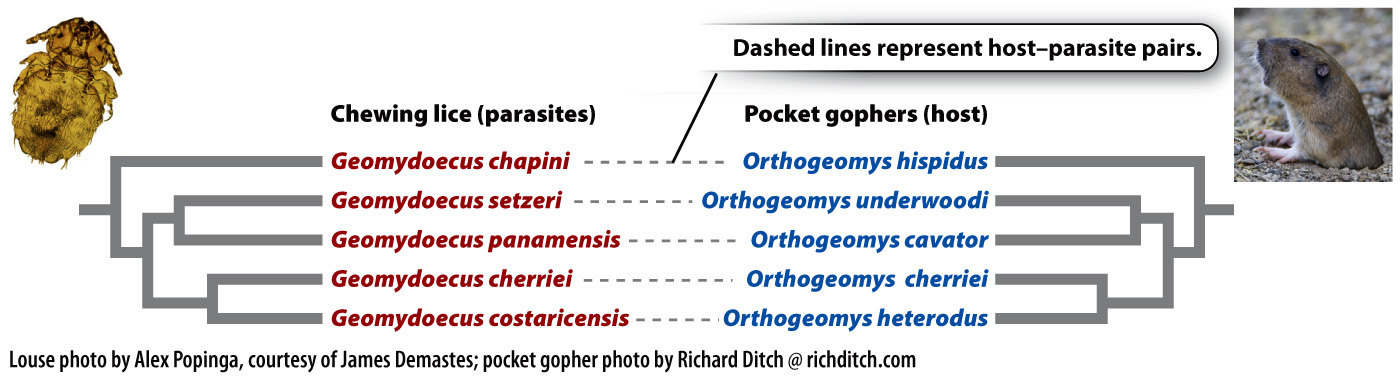

Phylogenetic analysis of lineages of parasites and their hosts that undergo co-speciation reveals trees that are similar for each group. Each time a branching event—that is, speciation—has occurred in one lineage, a corresponding branching event occurred in the other (Fig. 22.10).

FIG. 22.10 Co-speciation. Parasites and their hosts often evolve together, and the result is similar phylogenies. Sources: Data from J. P. Huelsenbeck and B. Rannala, 1997, “Phylogenetic Methods Come of Age: Testing Hypotheses in an Evolutionary Context,” Science 276:227, doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.227; Louse photo by Alex Popinga, courtesy of James Demastes; pocket gopher photo by Richard Ditch @ richditch.com.