Sympatric populations—

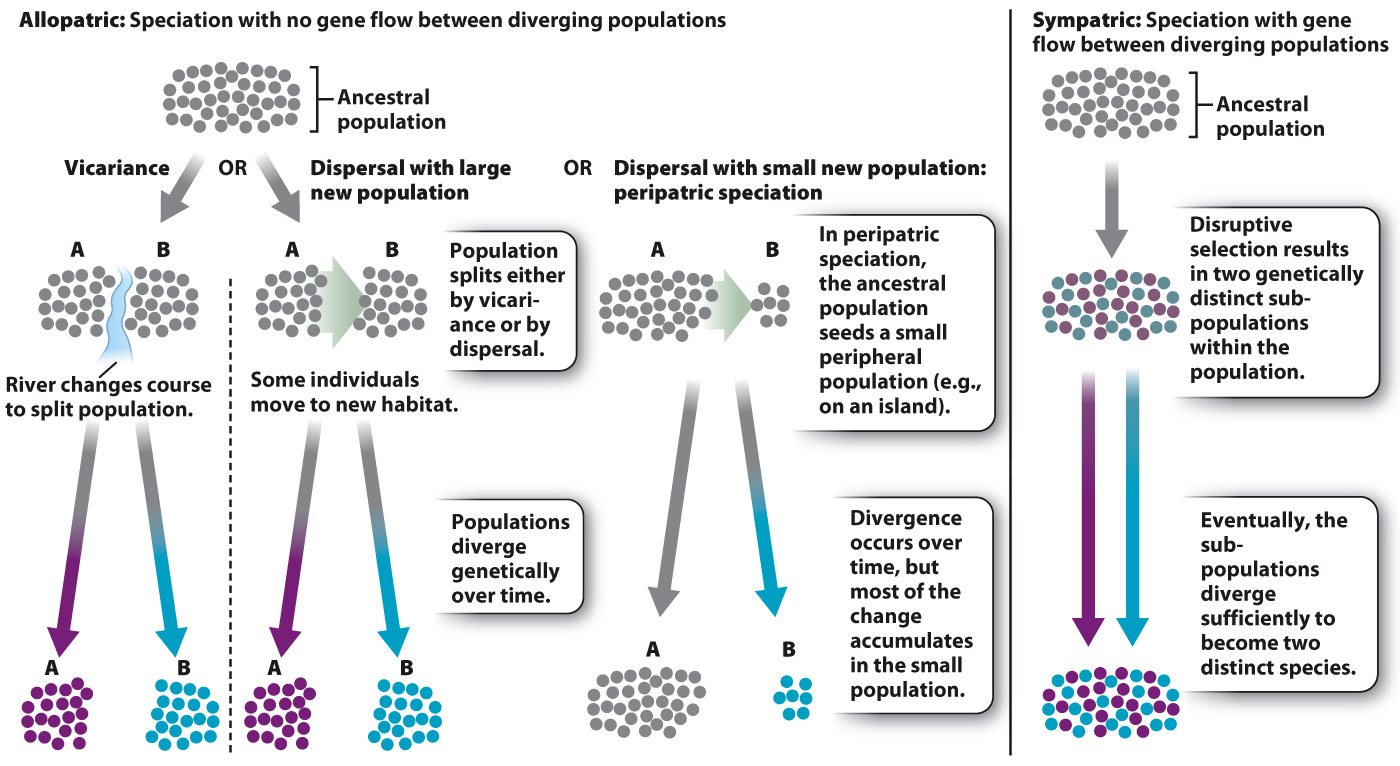

Can speciation occur without complete physical separation of populations? Yes, though evolutionary biologists are still exploring how common this phenomenon is. Recall how separated populations inevitably diverge genetically over time (see Fig. 22.6). If a mutation arises in population A after it has separated from population B, that mutation is present only in population A and may eventually become fixed (100% frequency) in that population, either through natural selection, if it is advantageous, or through drift, if it is neutral. Once the mutation is fixed in population A, it represents a genetic difference between populations A and B. Repeated independent fixations of different mutations in the two populations result over time in the genetic divergence of separated populations.

Now imagine that populations A and B are not completely separated and there is some gene flow between them. The mutation that arose in population A can, in principle, appear in population B as members of the two populations interbreed. The new mutation may indeed have become fixed in population A, but a migrant from population A to population B may introduce the mutation to population B as well. Gene flow effectively negates the genetic divergence of populations. If there is gene flow, a pair of populations may change over time, but they do so together. How, then, can speciation occur if gene flow exists? The term we use to describe populations that are in the same geographic location is sympatric (literally, “same place”). So we can rephrase the question in technical terms: How can speciation occur sympatrically?

457

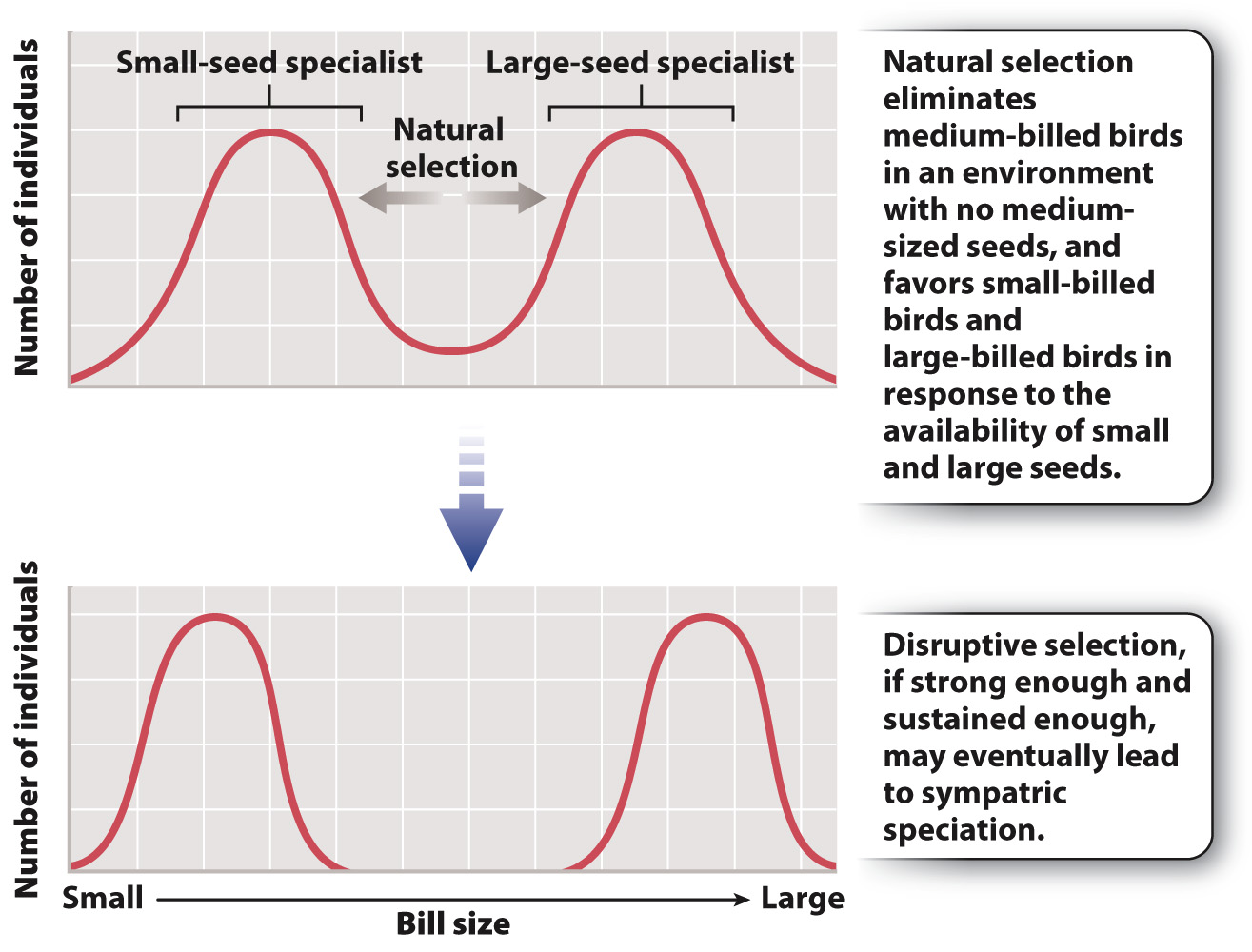

For speciation to occur sympatrically, natural selection must act strongly to counteract the homogenizing effect of gene flow. Consider two sympatric populations of finch-

However, it turns out to be difficult to find evidence of sympatric speciation in nature, though it may not be especially rare in plants, as we will see. We might find two very closely related species in the same location and argue that they must have arisen through sympatric speciation. However, there is an alternative explanation. One species could have arisen elsewhere by, for example, peripatric speciation and subsequently moved into the environment of the other one. In other words, the speciation occurred in the past by allopatry, and the two species are only currently sympatric because migration after speciation occurred.

However, recent studies of plants on an isolated island have provided strong, if not definite, evidence of sympatric speciation. Lord Howe Island is a tiny island (about 10 km long and 2 km across at its widest) about 600 km east of Australia. Two species of palm tree that are only found on the island are each other’s closest relatives. Because the island is so small, there is little chance that the two species could be geographically separated from each other, meaning that the species are and were sympatric, and, because of the distance of Lord Howe from Australia (or other islands), it is extremely likely that they evolved and speciated from a common ancestor on the island.

This and other demonstrations show that sympatric speciation can occur. We must recognize, however, that we do not yet know just how much of all speciation is sympatric and how much is allopatric. Fig. 22.12 summarizes modes of speciation based on geography.

458

Quick Check 3 There are hundreds of species of cichlid fish in Lake Victoria in Africa. Some scientists argue that they evolved sympatrically, but recent studies of the lake suggest that it periodically dried out, leaving a series of small ponds. Why is this observation relevant to evaluating the hypothesis that these species arose by sympatric speciation?

Quick Check 3 Answer

If populations of fish became separated from other populations of fish in different ponds during dry periods, this scenario suggests that speciation was more likely to be allopatric rather than sympatric. The allopatrically evolved species became sympatric only when the lake flooded again, combining all the separate ponds into a single body of water.