Rare mass extinctions have altered the course of evolution.

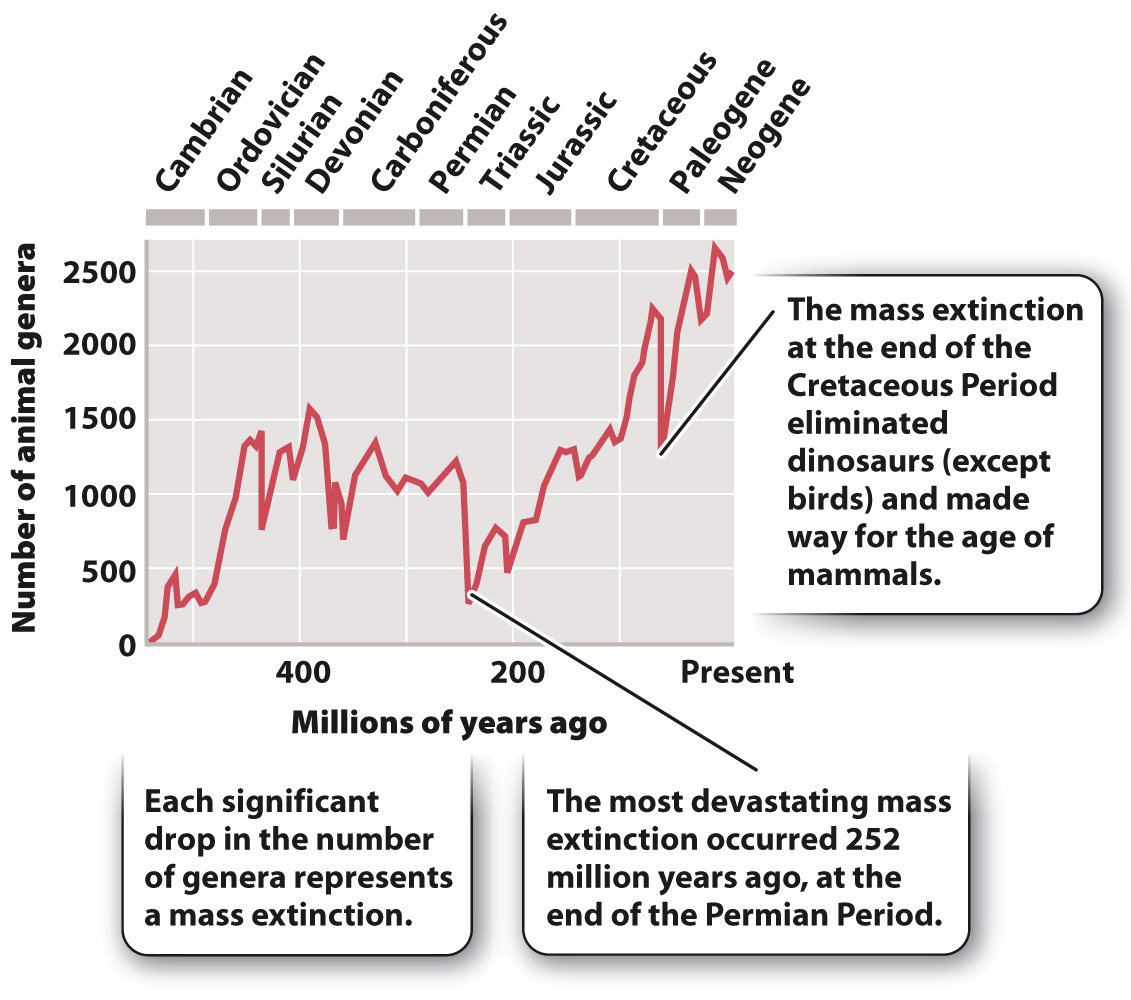

Beginning in the 1970s, American paleontologist Jack Sepkoski scoured the paleontological literature, recording the first and last appearances in the geologic record for every genus of marine animals he could find. The results of this monumental effort are shown in Fig. 23.21. Sepkoski’s diagram shows that animal diversity has increased over the past 540 million years: The biological diversity of animals in today’s oceans may well be higher than it has ever been in the past. But it is also clear that animal evolution is not simply a history of gradual accumulation.

Repeatedly during the past 500 million years, animal diversity in the oceans dropped both rapidly and substantially, and extinctions also occurred on land. Known as mass extinctions, these events eliminated ecologically important taxa and thereby provided evolutionary opportunities for the survivors. In Chapter 22, we explored how species often radiate on islands where there is little or no competition or predation. For survivors, mass extinctions provided ecological opportunities on a grand scale.

The best-

Before dinosaurs ever walked on Earth, the greatest of all mass extinctions occurred 252 million years ago, at the end of the Permian Period, when environmental catastrophe eliminated half of all families in the oceans and about 80% of all genera. Estimates of marine species loss run as high as 90%. Geologists have hypothesized that this mass extinction resulted from the catastrophic effects of massive volcanic eruptions. At the end of the Permian Period, most continents were gathered into the supercontinent Pangaea (see Fig. 23.18), and a huge ocean covered more than half of the Earth. Levels of oxygen in the deep waters of this ocean were low, the result of sluggish circulation and warm seawater temperatures. Then, a massive outpouring of ash and lava—

482

The three-

When you stroll through a zoo or snorkel above a coral reef, you are not simply seeing the products of natural selection played out over Earth history. You are encountering the descendants of Earth’s biological survivors. Current biological diversity reflects the interplay through time of natural selection and rare massive perturbations to ecosystems on land and in the sea. The fossil record provides a silent witness to our planet’s long and complex evolutionary history.