Taxonomic classifications are information storage and retrieval systems.

467

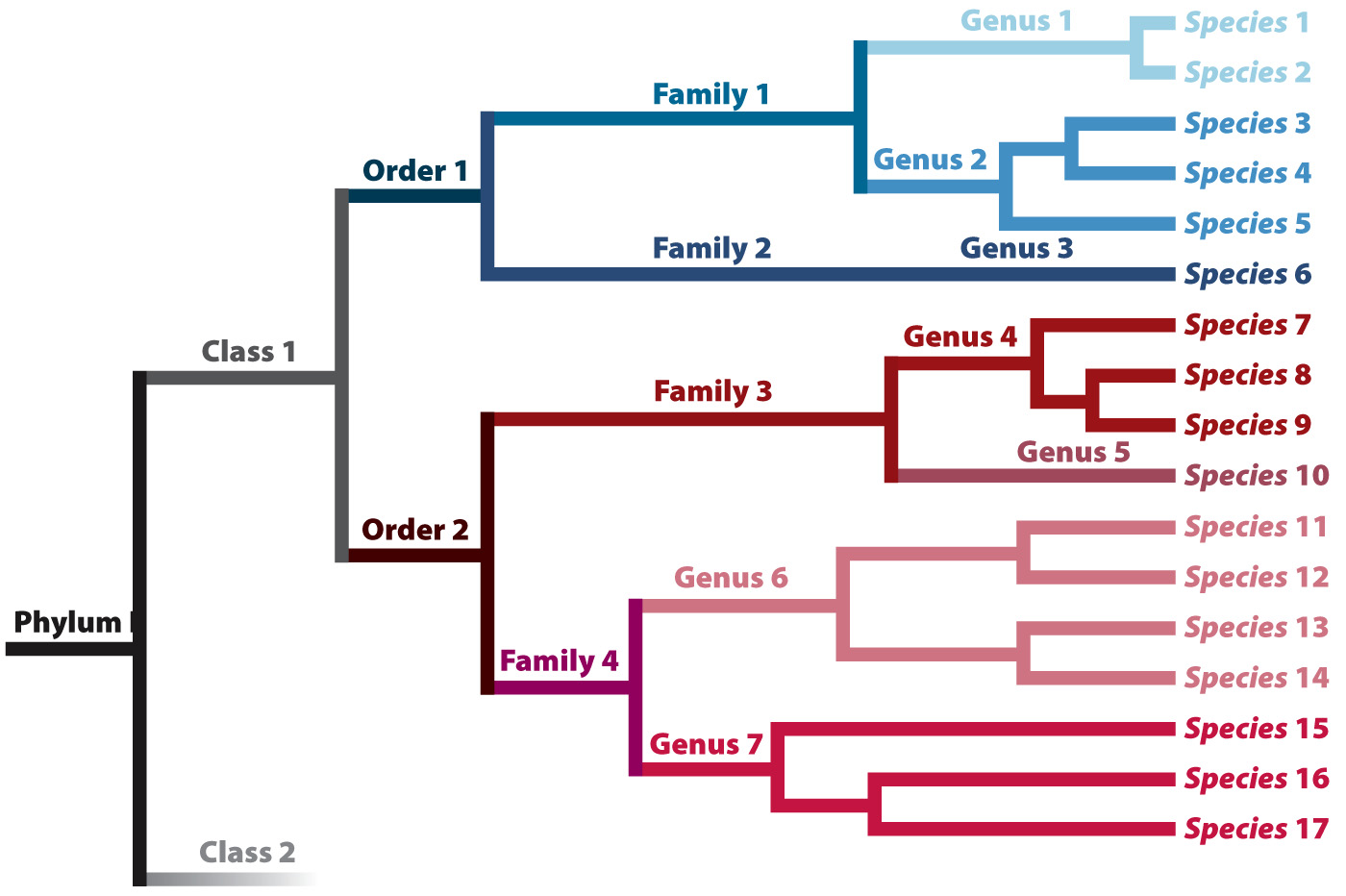

The nested pattern of similarities among species has been recognized by naturalists for centuries. In the vocabulary of formal classification, closely related species are grouped into a genus (plural, genera). Closely related genera, in turn, belong to a larger, more inclusive branch of the tree, as a family. Closely related families, in turn, form an order, orders form a class, classes form a phylum (plural, phyla), and phyla form a kingdom, each more inclusive taxonomic level occupying a successively larger limb on the tree (Fig. 23.5). Biologists today commonly refer to the three largest limbs of the entire tree of life as domains (Eukarya, or eukaryotes; Bacteria; and Archaea).

The ranks of classification form a nested hierarchy, but the boundaries of ranks above the species level are arbitrary in that there is nothing particular about a group that makes it, for example, a class rather than an order. A taxonomist examining the 17 species included in Fig. 23.5 might decide that species 3 and 4 are sufficiently distinct from species 5 to warrant placing them into a distinct genus. The same taxonomist might then decide that the grouping of the two new genera together should rank as a family. For this reason, it is not necessarily true that orders or classes of, for example, birds and ferns are equivalent in any meaningful way. In contrast, sister groups are equivalent in several ways—

468