Bipedalism was a key innovation.

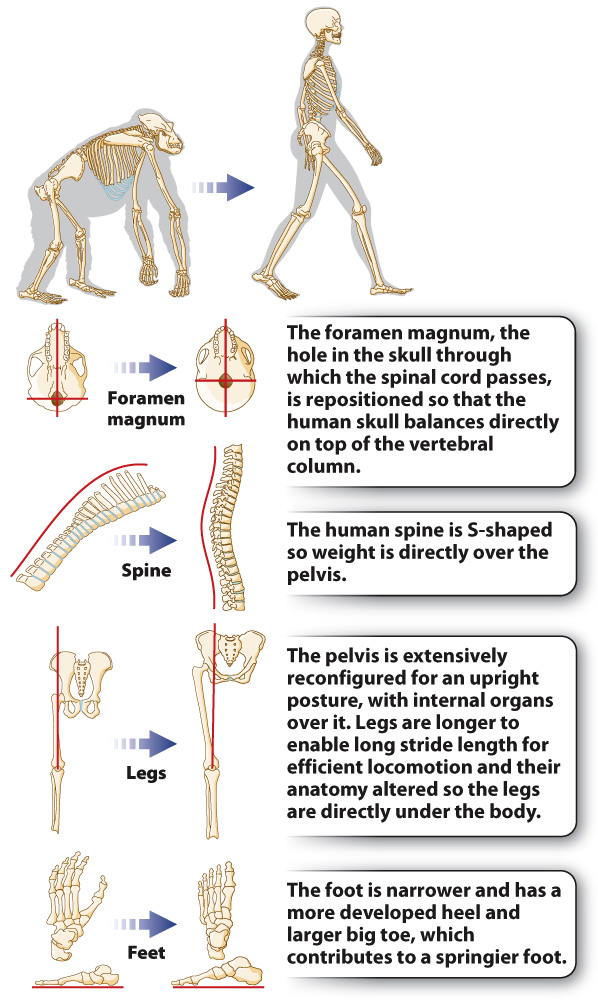

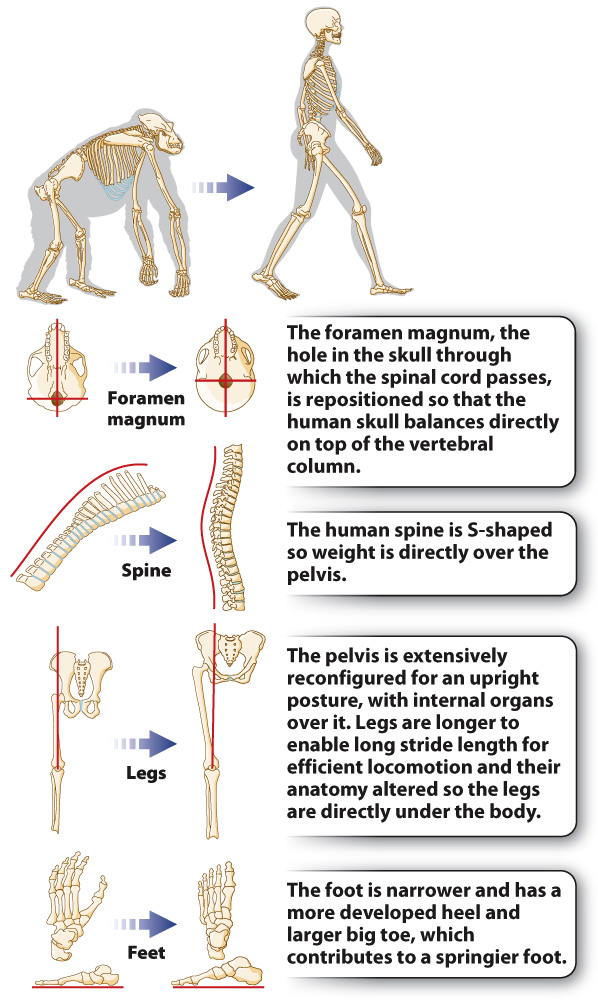

FIG. 24.11 The shift from four to two legs. Anatomical changes were required for the shift, especially in the structure of the skull, spine, legs, and feet.

The shift from walking on four legs to walking on two was probably one of the first changes in our lineage. Many primates are partially bipedal—chimpanzees, for example, may be observed knuckle-walking—but humans are the only living species that is wholly bipedal. As we’ve seen, Lucy, dating from about 3.2 million years ago, was already bipedal, and 4.4 million years ago, Ardi was partially bipedal. We can further refine our estimate of when full bipedalism arose from the evidence of a trace fossil. A set of 3.5-million-year-old fossil footprints discovered in Laetoli, Tanzania, reveal a truly upright posture.

Becoming bipedal is not simply a matter of standing up on hind legs. The change required substantial shifts in a number of basic anatomical characteristics, described in Fig. 24.11.

Why did hominins become bipedal? Maybe it gave them access to berries and nuts located high on a bush. Maybe it allowed them to scan the vicinity for predators. Maybe it made long-distance travel easier. Whatever the reason, bipedalism freed our ancestors’ hands. No longer did they need their hands for locomotion, so for the first time there arose the possibility that specialized hand function could evolve. Most primates have some kind of opposable thumb, but the human version is much more dexterous. The human thumb has three muscles that are not present in the thumb of chimpanzees, and these allow much finer motor control of the thumb. Tool use, present but crude in chimpanzees, can be much more subtle and sophisticated with a human hand.

Bipedalism also made it possible to carry material over long distances. Hominins could then set up complex foraging strategies whereby some individuals supplied others with resources. Exactly when sophisticated tool use arose in our ancestors is controversial, but it is indisputable that bipedalism contributed. Similarly, the ability to manipulate food with the hands, and to carry material using the hands rather than the mouth, likely permitted the evolution of the human jaw—indeed, the entire facial structure—in such a way that language became a possibility.