Adult humans share many features with juvenile chimpanzees.

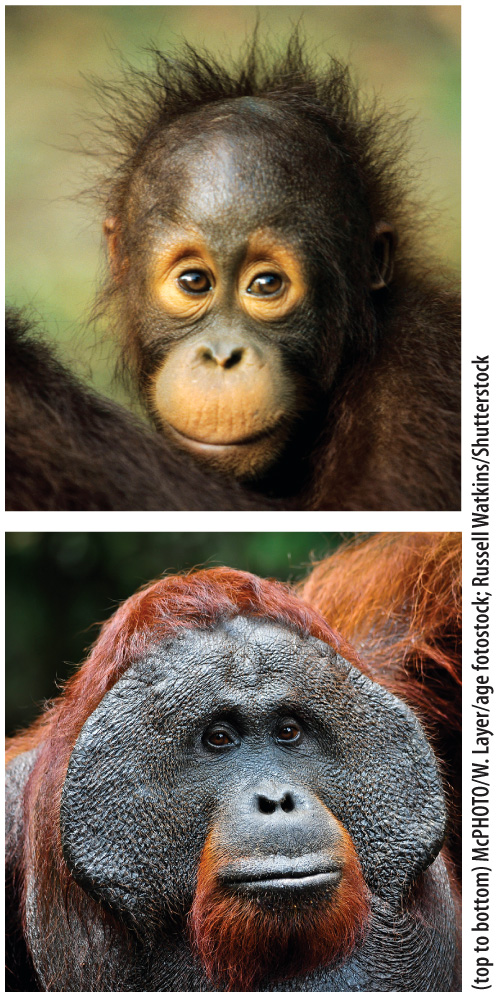

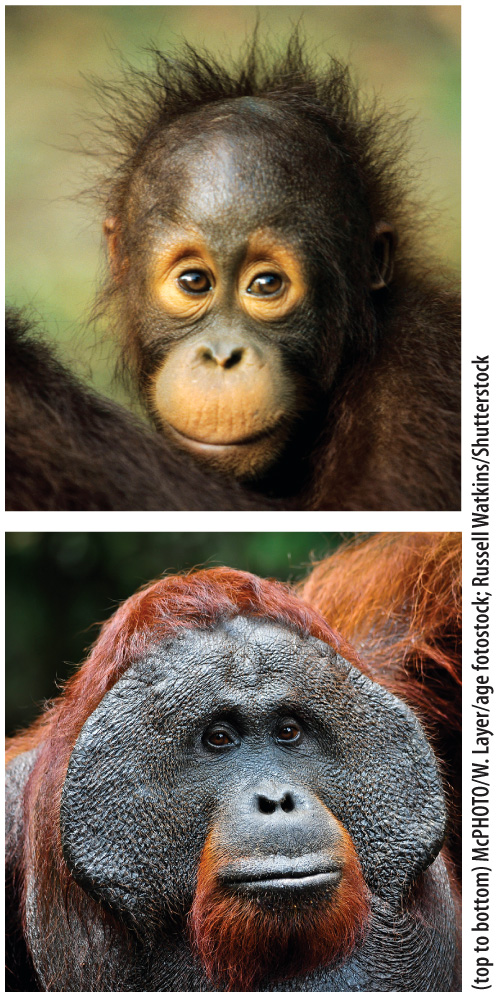

FIG. 24.12 A juvenile and an adult orangutan. Humans look more like juvenile orangutans than like adult orangutans, suggesting that humans may be neotenous great apes.

King and Wilson’s 1975 discovery that the DNA of humans and of chimpanzees are 99% identical has recently been confirmed by DNA sequence comparison of the human and chimpanzee genomes. It turns out that the two genomes are extraordinarily similar: All our genes are also present in the chimpanzee and their sequences in humans and in chimpanzees are extremely similar, suggesting that the functions of the proteins they code for are the same. If we are so similar, how can we account for the extensive differences between the two species?

In their original paper, King and Wilson suggested that much of the most significant evolution along the hominin lineage came about through changes in the regulation of genes (Chapter 19). A small change—one that causes a gene to be transcribed at a different stage of development, for example—can have a major effect. In other words, King and Wilson introduced a model whereby small changes in the software could have a major impact even though the basic hardware is the same.

One of the gene-regulatory pathways that changed may be responsible for human neoteny, the long-term evolutionary process in which the timing of development is altered so that a sexually mature organism still retains the physical characteristics of the juvenile form. In keeping with King and Wilson’s idea, this shift in development could conceivably be achieved with relatively little genetic change. All that it might take would be a few changes to the regulatory switches that control the timing of development.

As early as 1836, French naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire noted that a young orangutan on exhibit in Paris looked considerably more like a human than the adult of its own species (Fig. 24.12). Several human attributes support this model, including heads that are large relative to our bodies (and our correspondingly large brains), a feature of juvenile great apes. A second human attribute is our lack of hair. The juveniles of other great apes are not as hairless as humans, but they’re considerably less hairy than adult apes. A third attribute is the position of the foramen magnum at the base of the skull. In primate development, the foramen magnum starts off in the position it occupies in the adult human and then, in nonhuman great apes, migrates toward the back of the skull. Adult humans have retained the juvenile great ape foramen magnum position. Finally, it has been suggested that our mentality, with its questioning and playfulness, is equivalent in many ways to that of a juvenile ape rather than to that of the comparatively inflexible adult ape.