Case 5: How do intestinal bacteria influence human health?

CASE 5 THE HUMAN MICROBIOME: DIVERSITY WITHIN

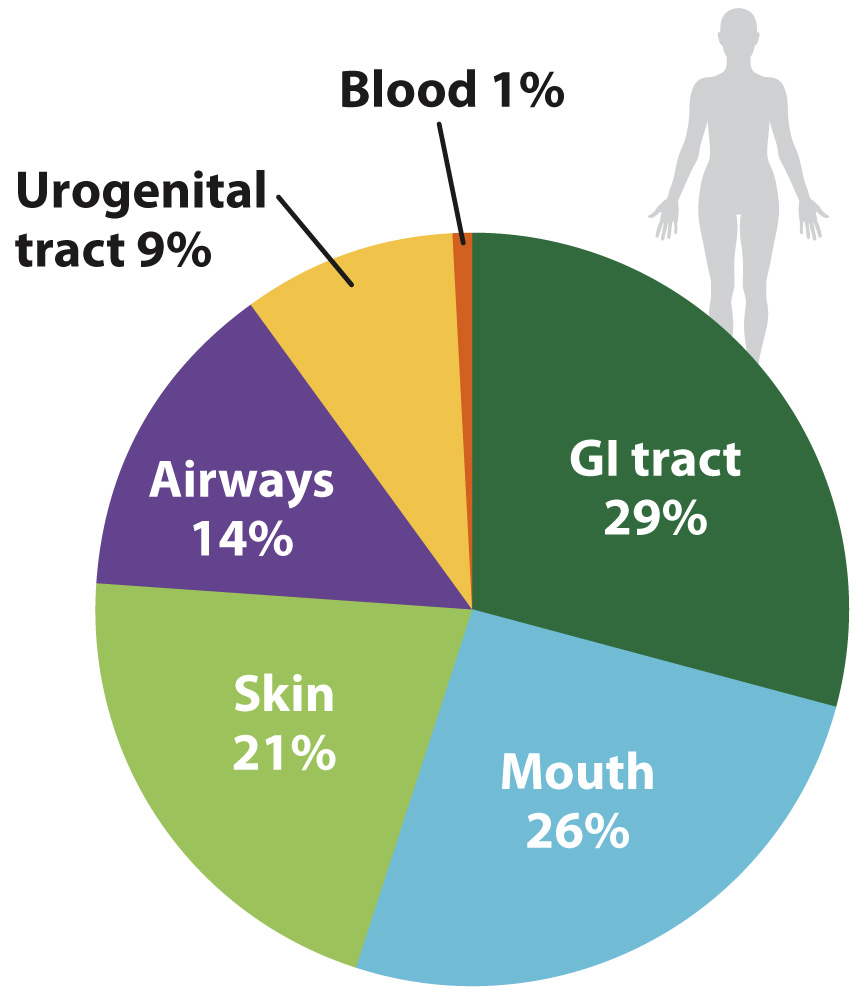

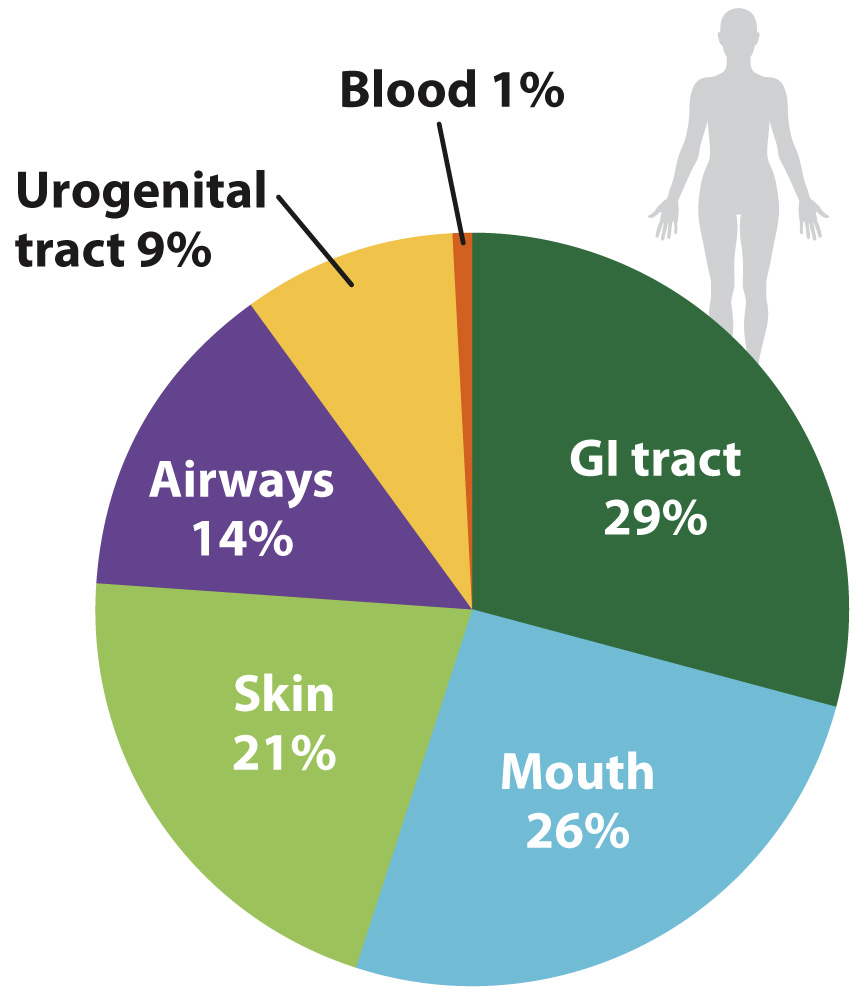

FIG. 26.23 The human microbiome. This chart provides a rough guide to the distribution of the 3000 or more species of bacteria found on and within a healthy human adult, showing the locations of bacteria that had been sequenced as of 2010. Source: Data from J. Peterson et al., 2009, “The NIH Human Microbiome Project,” Genome Research 19:2317–2323; originally published online October 9, 2009.

It has been estimated that the bacteria (and, to a much lesser extent, archaeons) in and on your body outnumber your own cells by as much as 10 to 1. Estimates of the number of microbial species that inhabit our bodies vary, but about 750 types have been identified in the mouth alone, and the list remains incomplete (Fig. 26.23). An equal number resides in the colon, and still more live on the skin and elsewhere. Some are transients, entering and leaving the body within a few bacterial generations. Others are specifically adapted for life within humans, forming complex communities of interacting species.

At present, much research is focused on the bacteria within our intestinal tracts. We commonly think of gut bacteria as harmful, but this perception arises from only a small—albeit devastating—subset of our microbial guests. Illnesses known to be caused by bacteria within our bodies include cholera, dysentery, and tuberculosis. Once the leading causes of death in New York and London, they remain major killers in Africa. Other diseases, not previously thought to be of microbial origin, are now known to be caused by bacteria—ulcers, for example, and stomach cancer, both mediated by the acid-tolerant bacterium Helicobacter pylori. More often than not, however, intestinal bacteria have a beneficial effect. They help to break down food in our digestive system and secrete vitamins and other biomolecules into the colon for absorption into our tissues. Molecular signals from bacteria guide the proper development of cells that line the interior of our intestines.

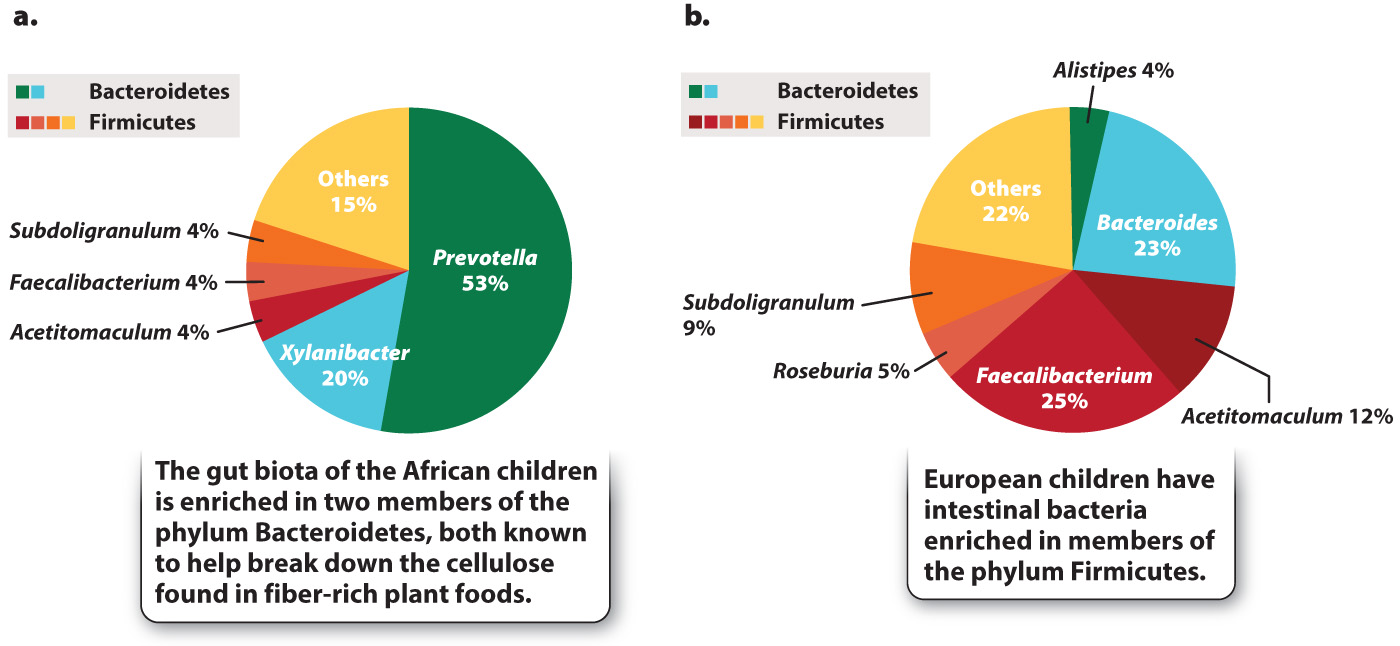

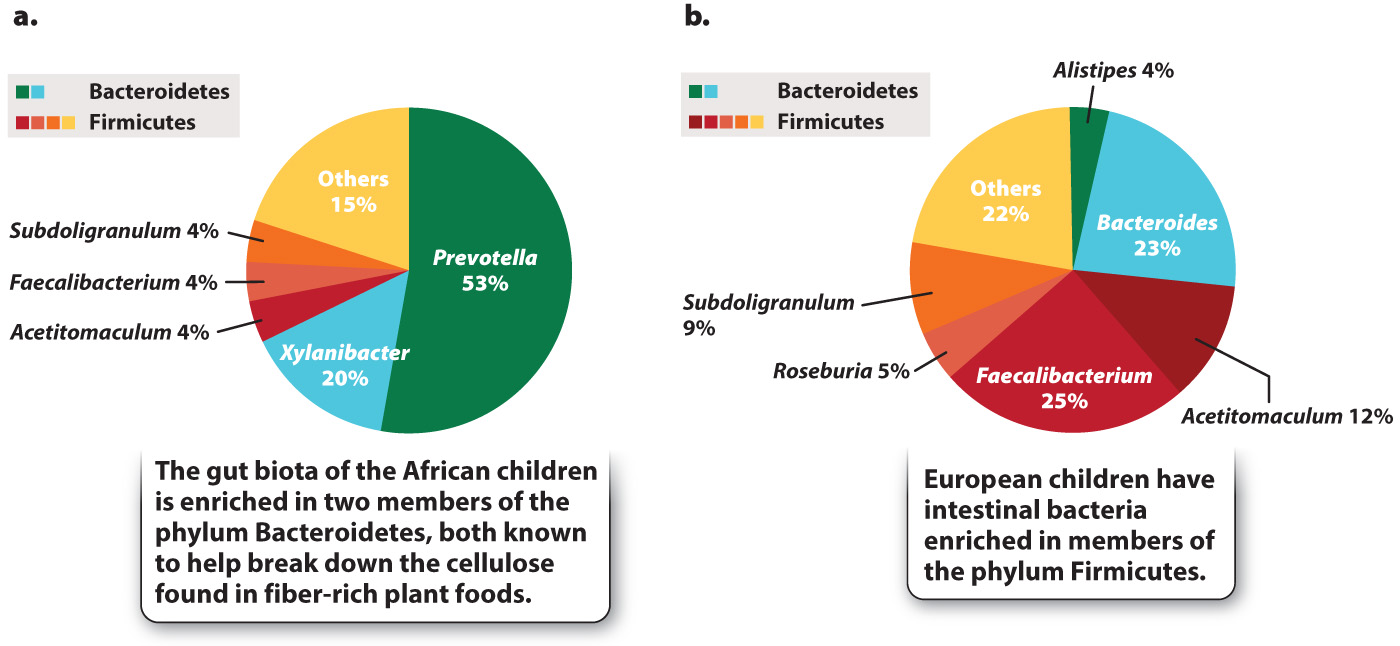

A fertilized human egg has no bacteria attached to it, so our microscopic passengers arrive by colonization—by infection, if you will. Research on children from Europe and rural Africa clearly shows the importance of diet in establishing our gut microbiota (Fig. 26.24). The African children, raised on a diet low in fat and animal protein but rich in plant matter, have gut microbiotas enriched in species of the phylum Bacteroidetes that are known to help digest cellulose. European children raised on a typical Western diet rich in sugar and animal fat lack these bacteria, harboring instead diverse members of the phylum Firmicutes. We do not understand the full ramifications of these differences, but active research suggests that they may help to explain the relative prominence in Western societies of allergies and other disorders involving the immune system.

FIG. 26.24 Diet and the intestinal microbiota. Studies of gut bacteria in children from (a) rural Africa and (b) Western Europe show markedly different communities. Source: Data from C. De Filippo, D. Cavalieri, M. Di Paola, M. Ramazzotti, J. B. Poullet, S. Massart, S. Collini, G. Pieraccini, and P. Lionetti, 2010, “Impact of Diet in Shaping Gut Microbiota Revealed by a Comparative Study in Children from Europe and Rural Africa,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 107(33):14693, doi:10.1073/pnas.1005963107.

We also influence our gut biota by ingesting antibiotics. Although prescribed for the control of pathogens, most antibiotics kill a wide range of bacteria and so can change the balance of our intestinal microbiota. Clinical studies show that the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease, a disabling inflammation of the colon, increases in humans who have been treated with antibiotics.

To understand the relationships between the human microbiome and human health, we need to know what constitutes a healthy gut biota, and this means studying the metabolism, ecology, and population genetics of the bacteria in our bodies. We need to know which bacteria have evolved to take advantage of the environments provided by the human digestive system, and which are “just passing through.” Future visits to the doctor may include routine genetic fingerprinting of our bacterial biota, as well as treatments designed to keep our microbiome—and, so, ourselves—healthy.