Xylem provides a low-

Water travels with relative ease through xylem: It would take 10 orders of magnitude greater force to drive water through living parenchyma cells than it takes to drive the same amount of water through the xylem. This ease of flow is explained by the structure of the water-

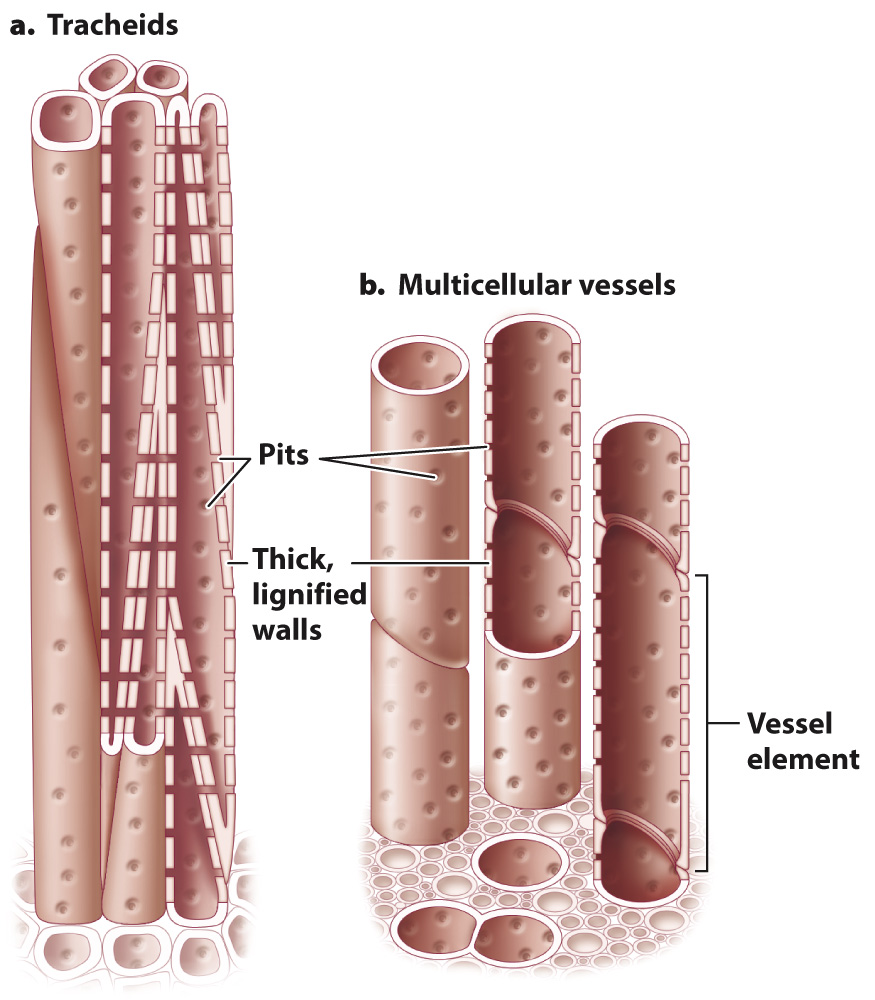

The walls of xylem conduits are thick and contain lignin, a chemical compound that increases mechanical strength and also prevents water from passing through the cell wall. Water enters and exits xylem conduits through pits, circular or ovoid regions where the lignified cell wall layer was not produced. Instead, pits contain only the thin, water-

A xylem conduit can be formed from a single cell or from multiple cells stacked to form a hollow tube. Unicellular conduits are called tracheids (Fig. 29.10a), and multicellular conduits are called vessels (Fig. 29.10b). Because tracheids are the product of a single cell, they are typically 5–

Water enters a tracheid through pits, travels upward through the conduit interior, and then flows outward through other pits into an adjacent, partially overlapping, tracheid. Water also enters and exits a vessel through pits. Once the water is inside the vessel, little or nothing blocks the flow of water from one vessel element to the next. That is because during the development of a xylem vessel, the end walls of the vessel elements are digested away, allowing water to flow along the entire length of the vessel without having to cross any pits. At the end of a vessel, however, the water must flow through pits if it is to enter an adjacent vessel and thereby continue its journey from the soil to the leaves.

608

The rate at which water moves through xylem depends on both the number of conduits and their size. Water flows faster through longer conduits because the water does not need to flow so often from conduit to conduit across pits, which exert a significant resistance to flow. Like the flow through pipes, water flow through xylem conduits is also greater when the conduits are wider. The flow is proportional to the radius of the conduit raised to the fourth power, so doubling the radius increases flow sixteenfold. Because vessels are both longer and wider than tracheids, plants with vessels achieve greater rates of water transport. Tracheids are the type of xylem conduit found in lycophytes, ferns and horsetails, and most gymnosperms, whereas vessels are the principal conduit in angiosperms.