Roots grow by producing new cells at their tips.

In Chapter 29, we saw that plants produce large numbers of thin roots to obtain sufficient nutrients from the soil. And to obtain water during periods without rain, plants produce roots that penetrate deep into the soil. Growing roots into the soil presents challenges different from those associated with elongating stems into the air. Although the dangers of drying out are much reduced belowground, deeper soil layers can have densities approaching that of concrete. How are the thin and permeable roots needed for water and nutrient uptake able to penetrate and grow through the soil?

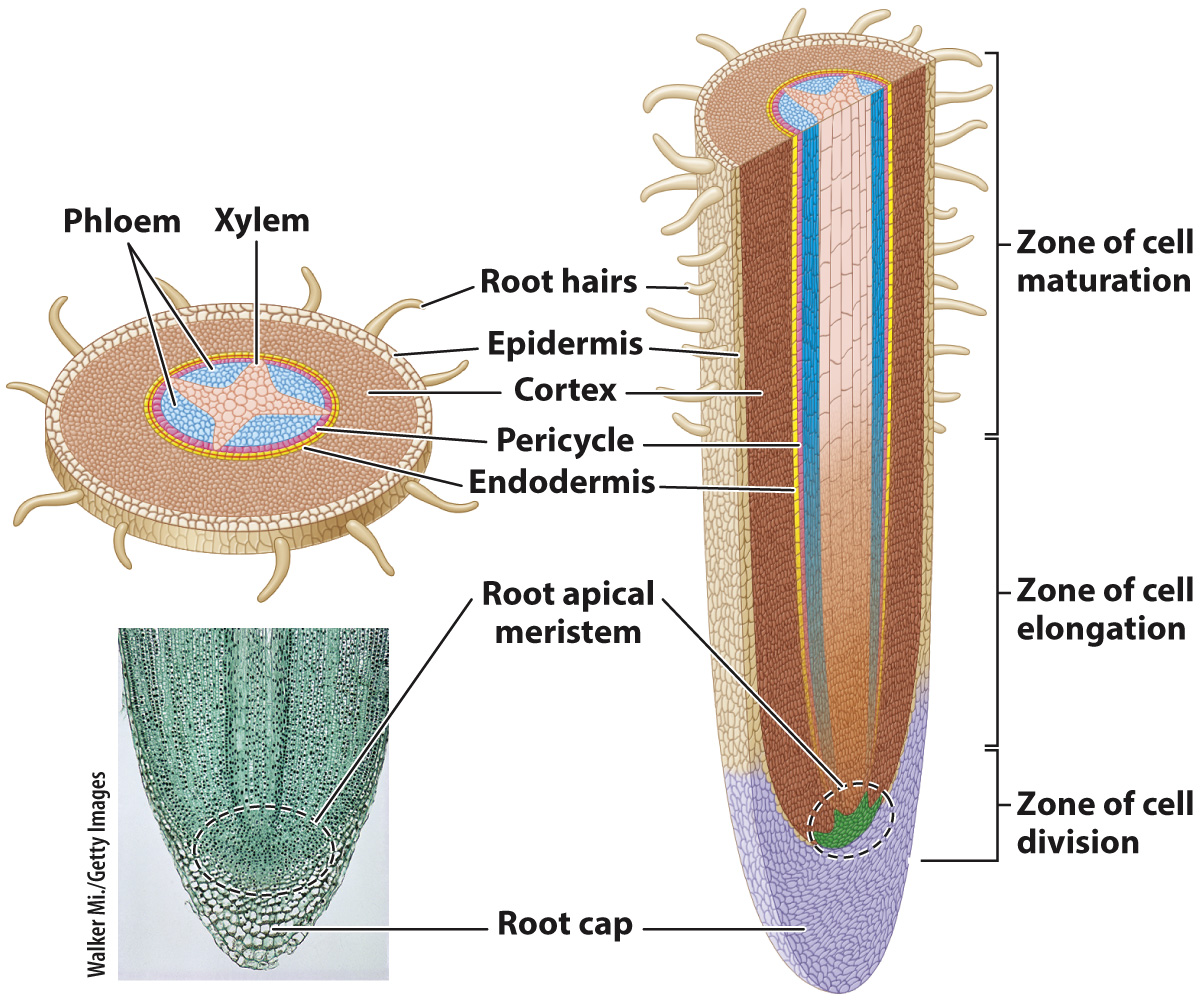

In one respect, roots grow in the same way as shoots in that new cells are produced at their tip. The root apical meristem is the source of new cells. After cell division, these cells elongate and become differentiated. They complete their differentiation only after elongation has ceased (Fig. 31.16). Thus, as we move back from the tip of the elongating root, we encounter successive regions of cell division, elongation, and maturation, just as we saw in stems.

Roots, however, differ from stems in several important ways. One difference is that roots are much thinner than stems. Plants with thin roots can more efficiently produce the large surface area needed for uptake of water and nutrients from the soil. Thin roots can also more easily bend around soil particles and make use of channels made by invertebrate animals that burrow through the soil. A second difference is that the root apical meristem is covered by a root cap that protects the meristem as it grows through the soil. As the root elongates through the soil, root cap cells are rubbed off or damaged. Thus, the root cap is continually supplied with new cells produced by the root apical meristem. A third difference between roots and stems, and one that can be seen without a microscope, is that the root apical meristem does not produce any lateral organs, whereas the shoot apical meristem makes leaves. Root hairs, the single-