Flowering time is affected by day length.

In the 1910s, Wightman Garner and Henry Allard, scientists at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, set out to understand why Maryland Mammoth, a variety of tobacco, does not produce flowers during the summer like other tobacco plants. Instead, these plants continue to grow throughout the summer, reaching heights several times that of a typical tobacco plant and producing many more leaves. Only in autumn does the Maryland Mammoth tobacco plant finally produce flowers, too late in the year for seeds to mature.

One possible explanation for the observed delay in flowering time is that Maryland Mammoth must achieve a greater size before it produces flowers. However, when Garner and Allard grew Maryland Mammoth plants in a heated greenhouse during the winter, the plants flowered at the same time and size as other tobacco plants. Therefore, size does not determine when Maryland Mammoth flowers. Because the heated greenhouse was set to the same temperatures as those found during the summer, temperature could also be eliminated as a factor. Garner and Allard were left with only one environmental variable that was different between the summer and the winter: the length of the day.

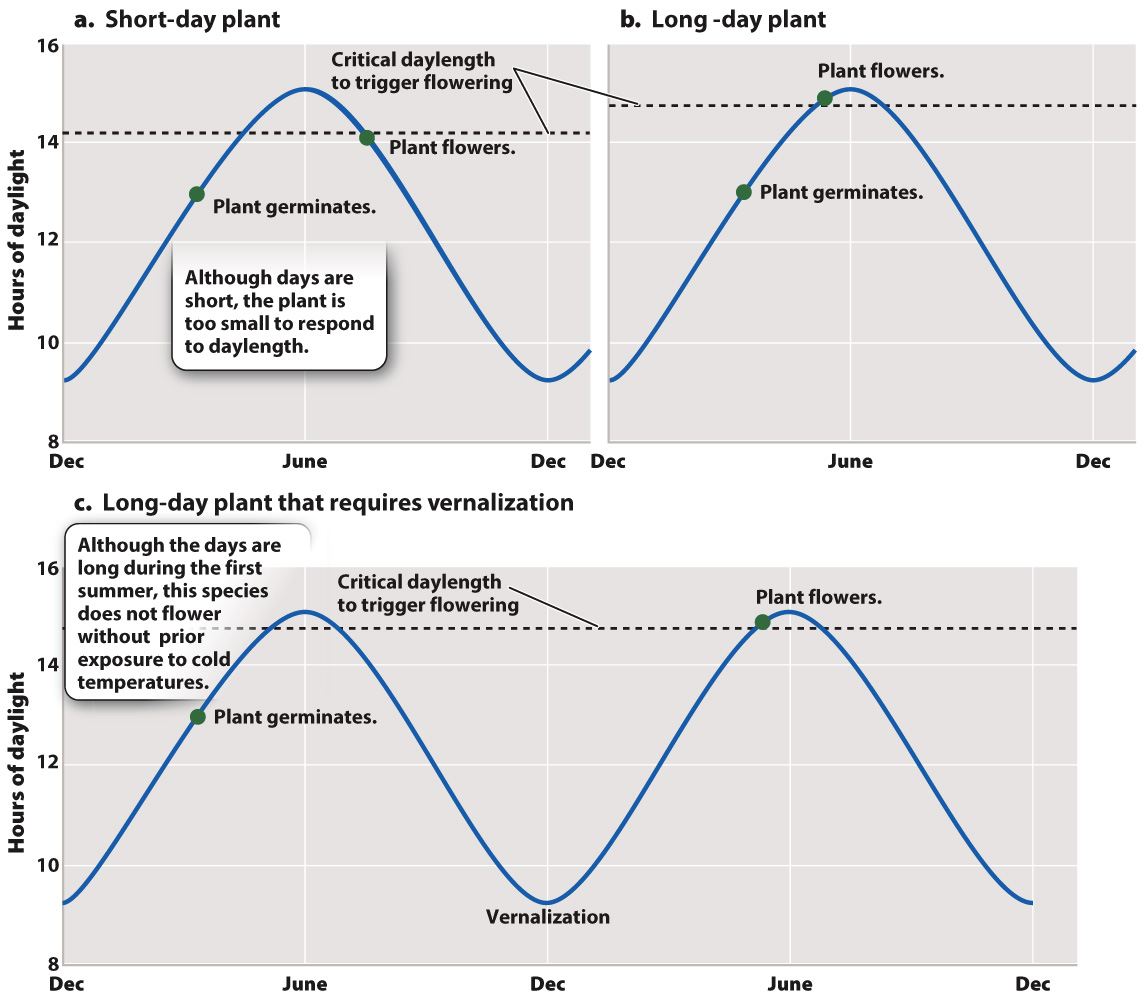

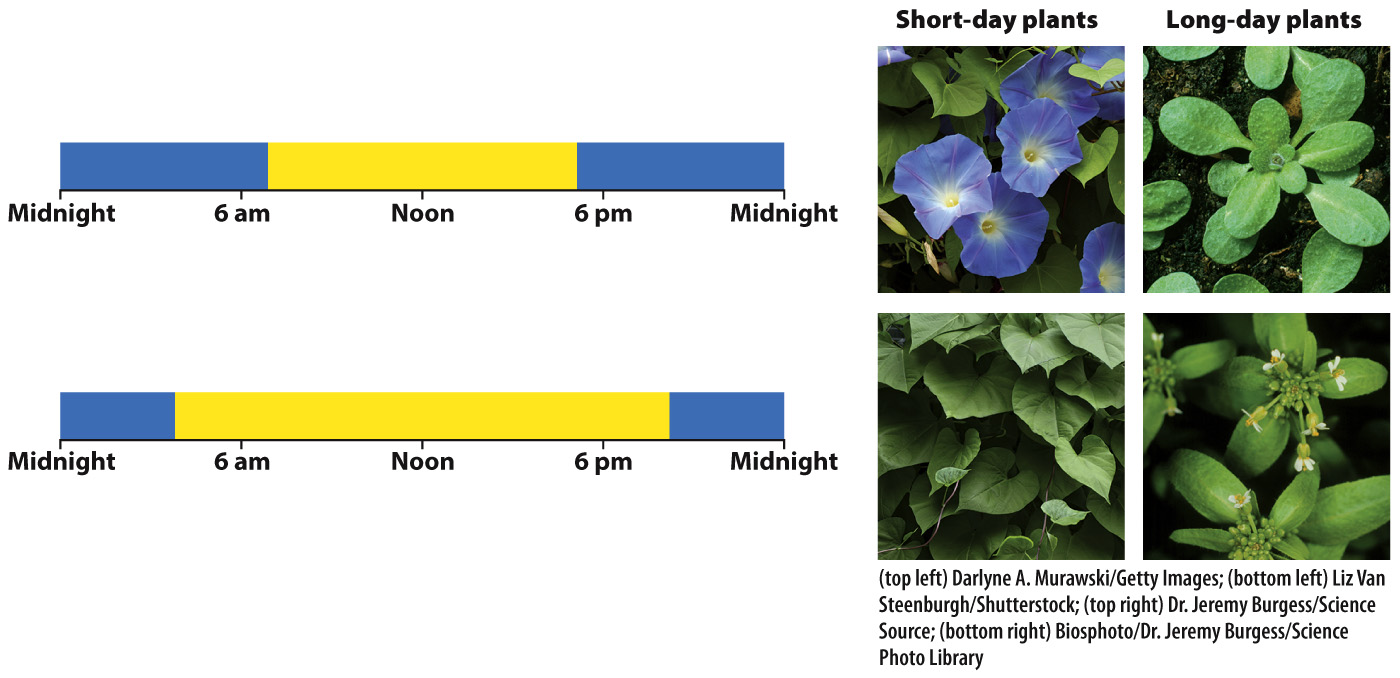

In a series of experiments in the early part of the last century, Garner and Allen artificially shortened the day length during summer and extended it during winter. Their results showed that in Maryland Mammoth, as well as in many other plants, flowering is controlled by day length. They coined the term photoperiodism to describe the effect of the “photo period,” or day length, on flowering (Fig. 31.25). Short-

Sensitivity to day length ensures that plants flower only when they are large enough to support the development of a large number of seeds and there is enough time for those seeds to mature before the onset of winter. A short-

663