Plants can sense and respond to herbivores.

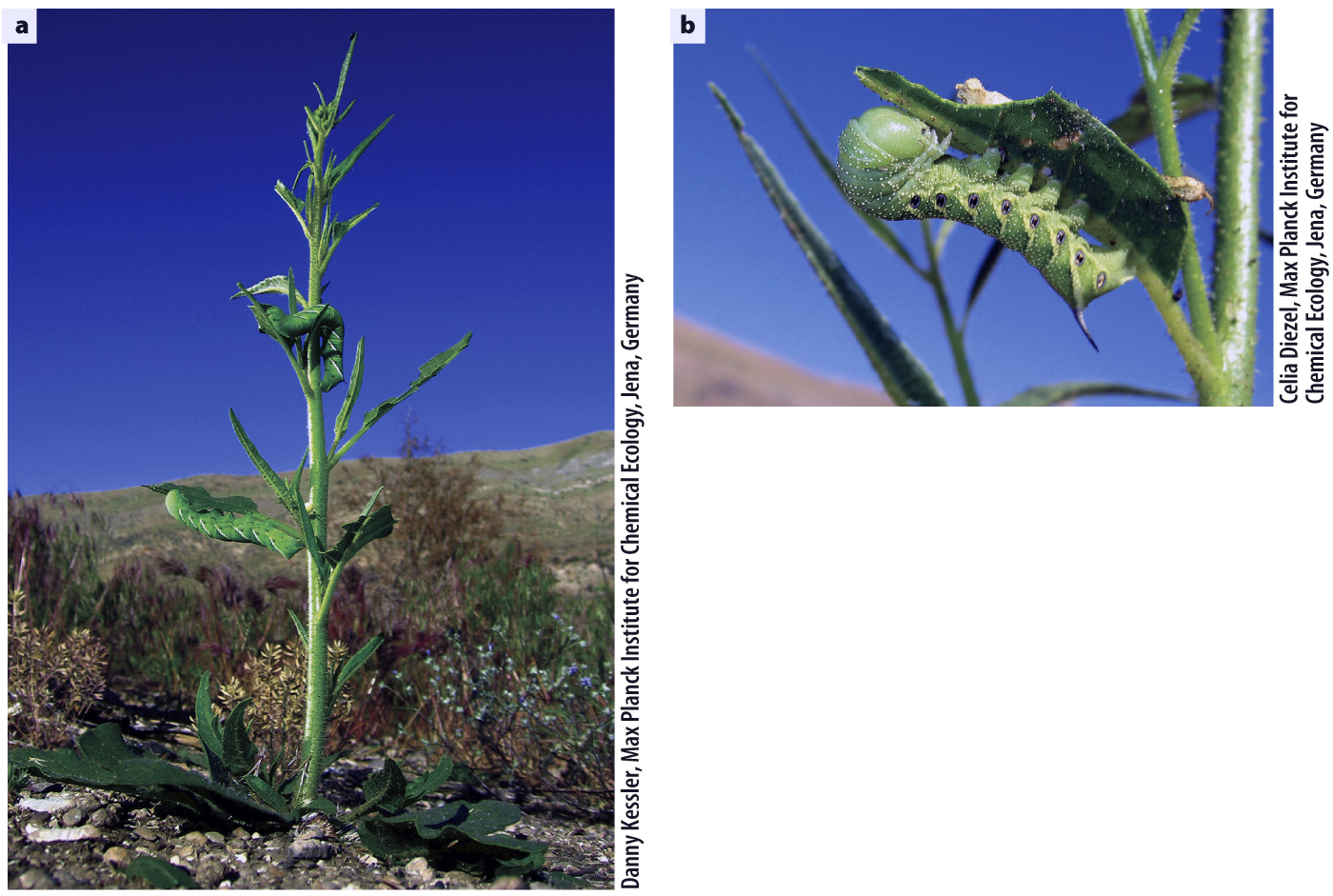

For more than 15 years, biologists have studied how coyote tobacco (Nicotiana attenuata), a relative of tobacco native to dry open habitats of the American West (Fig. 32.15), defends itself against herbivores. These studies provide a fascinating window into how plants allocate resources toward defense under natural conditions.

680

Nicotiana attenuata is attacked by a wide variety of herbivores, both generalists and specialists. A major component of N. attenuata’s defense against being eaten is the production of the alkaloid nicotine. Nicotine is an effective defense against many generalist herbivores. However, nicotine is also an expensive form of chemical defense because it contains nitrogen, a nutrient whose availability can limit growth. Thus, N. attenuata plants that have not been exposed to herbivores produce only low levels of nicotine as a constitutive defense. When N. attenuata is attacked by a generalist herbivore, nicotine concentrations in leaves increase dramatically—

Nicotiana attenuata is also attacked by a specialist herbivore, the tobacco hornworm caterpillar, Manduca sexta. These caterpillars, which can reach 7 cm in length, have evolved the ability to sequester and secrete nicotine. By this means, these caterpillars are able to consume leaves with high levels of nicotine. If nicotine is not an effective defense against this voracious herbivore, what can N. attenuata do to protect itself?

It turns out that N. attenuata can recognize specific chemicals in the saliva of M. sexta. When damaged by most herbivores—