Rhynie cherts provide a window into the early evolution of vascular plants.

Fossils recovered from a single site in Scotland document key stages in the evolution of vascular plants. Four hundred million years ago, near the present-

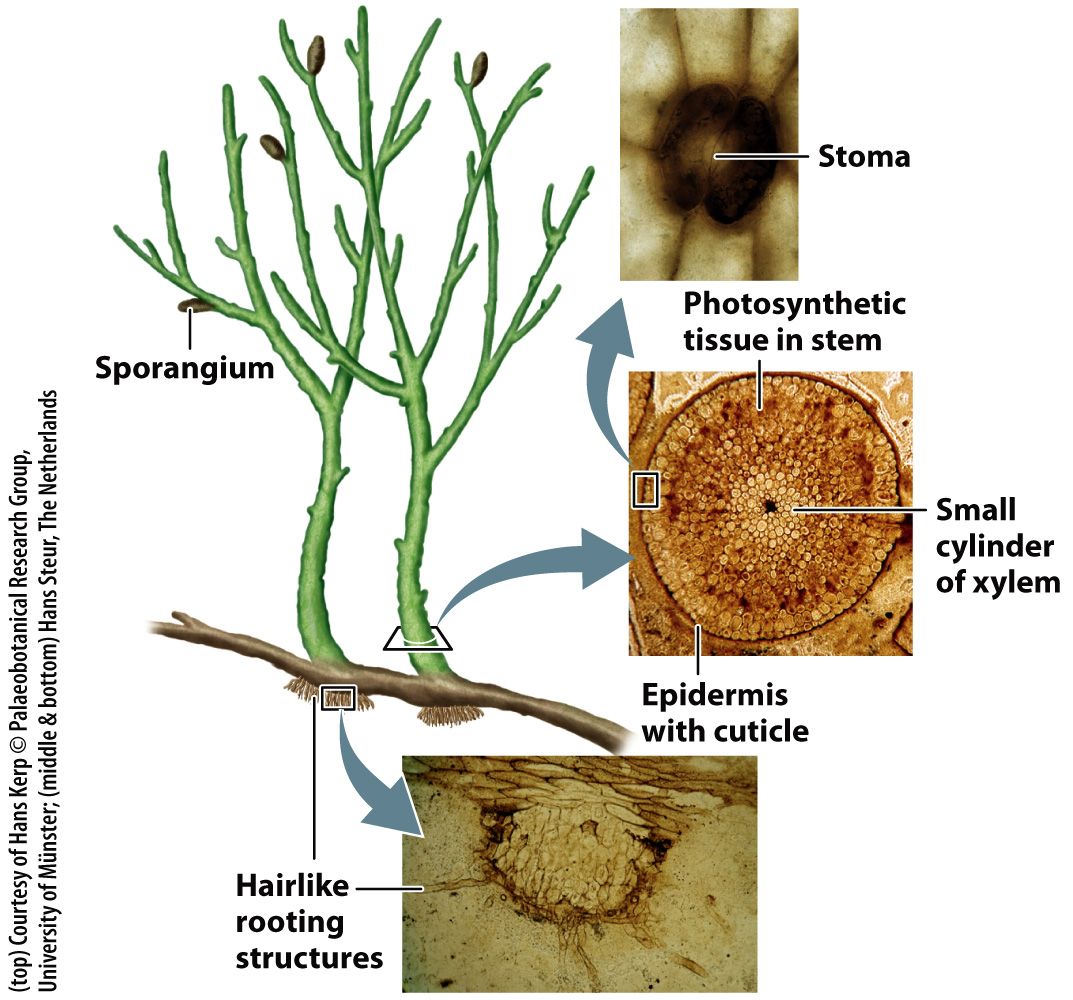

Rhynie cherts provide our best view of early vascular plants. These plants were small (up to about 15 cm tall) photosynthetic structures that branched repeatedly, forming sporangia at the tips of short side branches (Fig. 33.6). They had no leaves, and their only root structures were small hairlike extensions on the lower parts of stems that ran along the ground. The stems had a cuticle with stomata, and a tiny cylinder of vascular tissue ran through the center. Many of the gametophytes also had erect cylindrical stems, not at all like the reduced gametophytes of living vascular plants.

694

Rhynie cherts provide another important glimpse of early plant evolution: Some fossils have a branched sporophyte that includes cell walls that are reinforced with lignin, but there is no evidence of vascular tissue. Evidently, plants evolved the upright stature we associate with living vascular plants before they evolved the differentiated tissues of the vascular system (xylem and phloem). Once vascular tissues had evolved, however, they played a key role in shaping subsequent evolution of the plant sporophyte.