Cycads and ginkgos are the earliest diverging groups of living gymnosperms.

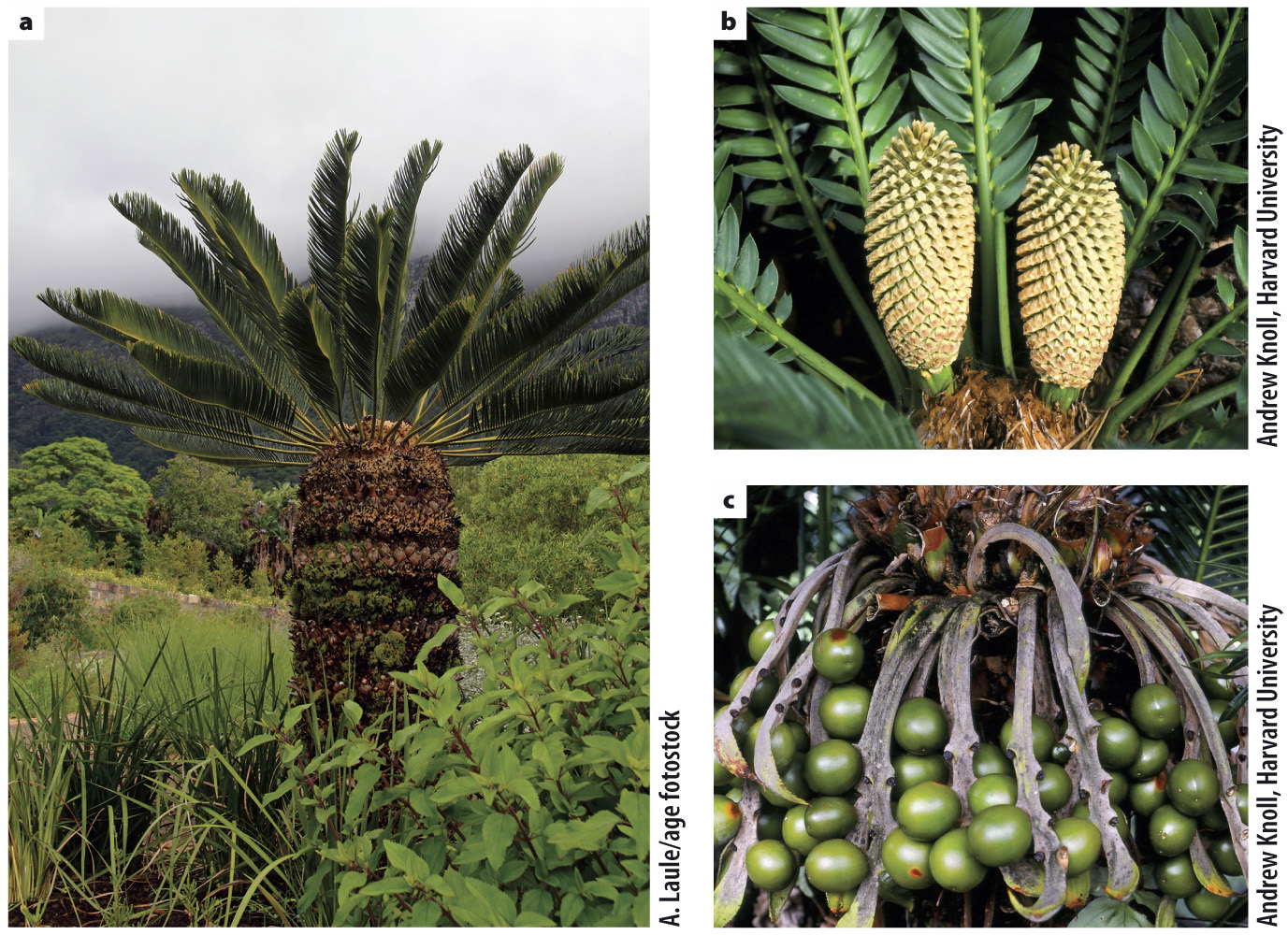

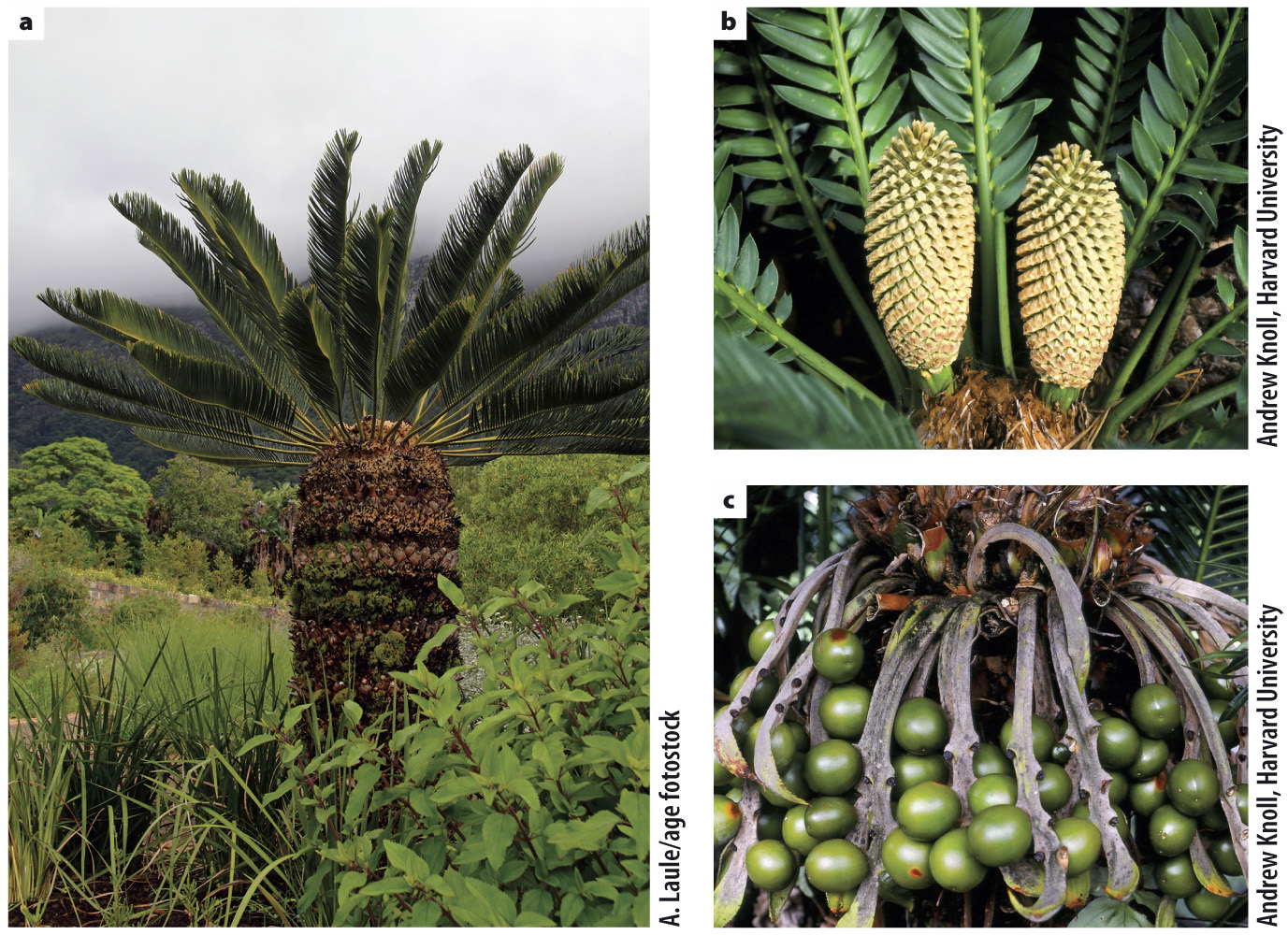

It’s easy to confuse cycads with palm trees because both have unbranched stems and large leaves (Fig. 33.15). However, the presence of cones rather than flowers clearly marks cycads as gymnosperms. Cones are modified branch tips inside which reproductive structures develop, with pollen and ovules produced in separate cones. In cycads, the cones are large and woody, and thus provide protection for the developing pollen and seeds.

FIG. 33.15 Cycads. (a) Most living cycads have thick, unbranched stems that support large leaves and cones. Shown here is Encephalartos friderici-guilielmi. (b) Many cycads, such as Encephalartos transvenosus, have large cones. (c) Mature seeds are large (here are shown those of Cycas circinalis) and contain a relatively large female gametophyte that provides nutrition for the embryo and germinating sporophyte.

Cycads have low photosynthetic rates and they grow slowly. Although they have large stems, their vascular cambium produces little additional xylem, and most of their bulk is made up of unlignified (nonwoody) cells in the center of the stem (pith) and surrounding the vascular tissues (cortex). Cycads are able to grow in nutrient-poor environments by forming symbiotic associations with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria. Cycads are also able to survive wildfires because their apical meristem is protected by a dense layer of bud scales.

The approximately 300 species of cycads occur most commonly in tropical and subtropical regions. Most species have a limited and often fragmented distribution, suggesting that they were much more widespread in the past. Most cycad populations are small and often vulnerable to extinction. Cycads may owe their persistence in part to the fact that they rely on insects for pollination, as well as to their ability to live in nutrient-poor and fire-prone environments. Insects transfer pollen more efficiently than wind, and therefore insect-pollinated species with small populations are able to reproduce successfully. Many cycads are pollinated by beetles, which are attracted by chemical signals produced by the cones. The large seed cones provide shelter for the insects, and the pollen cones provide them with food. Following fertilization, brightly colored, fleshy seed coats attract a variety of birds and mammals that serve as dispersal agents. Because of their small numbers and fragmented distribution, two-thirds of all cycads are on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s “red list” of threatened species, the highest percentage of any group of plants.

Cycads are an ancient group, with fossils at least 280 million years old. During the time of the dinosaurs, they were among the most common plants. Cycad diversity and abundance declined markedly during the Cretaceous Period, at the same time the angiosperms rose to ecological prominence. A recent study shows that present-day cycad species date from a burst of speciation that took place approximately 12 million years ago. At that time, the positions of the continents and ocean circulation patterns were changing in such a way that climates became increasingly cooler and more seasonal. This climate change provided new habitats for emerging species while dooming older species to extinction.

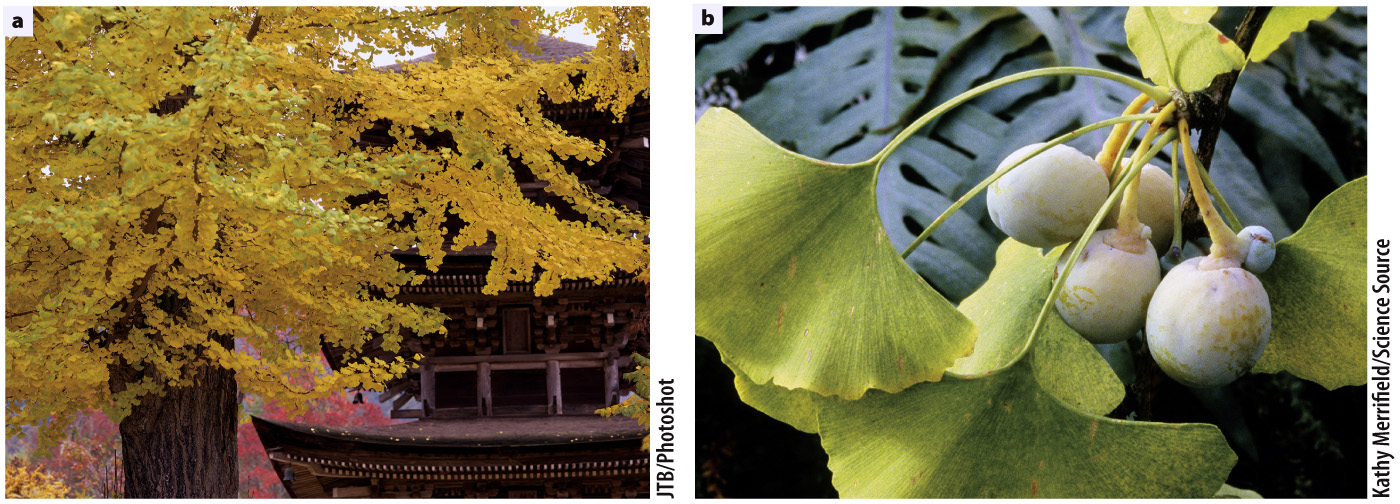

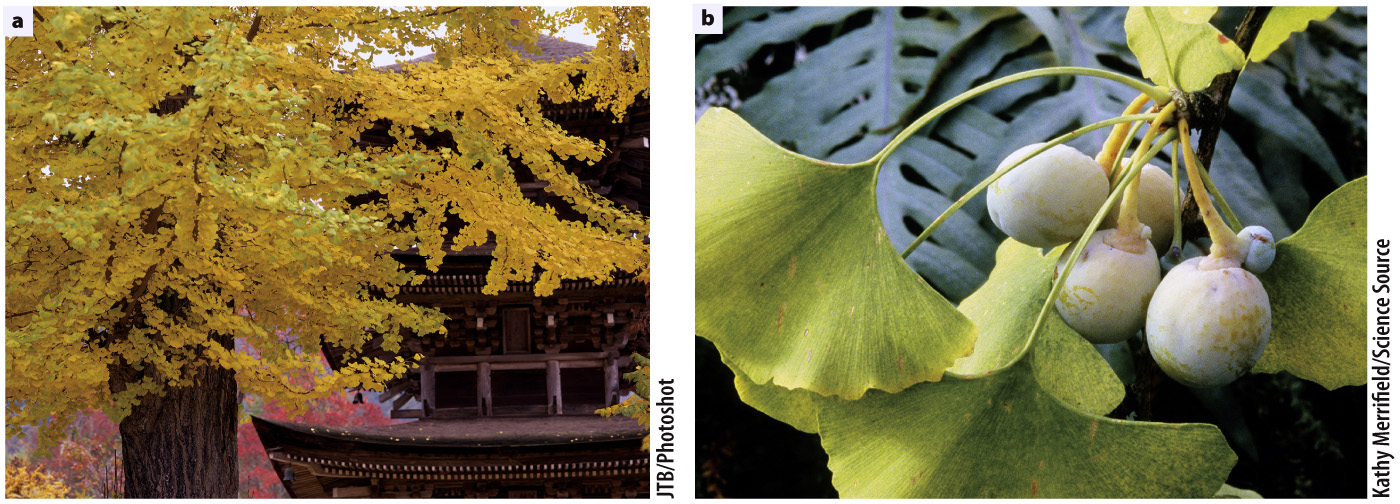

A second group of gymnosperms has only a single living representative: Ginkgo biloba. This species forms tall, branched trees, with fan-shaped leaves that turn brilliant yellow in autumn (Fig. 33.16). Ginkgo is wind pollinated, but, like cycads, develops fleshy seeds, perhaps a feature inherited from their common seed plant ancestor. Ginkgos date back about 270 million years, and during the time of the dinosaurs, they were common trees in temperate forests. Like cycads, ginkgos declined in abundance, diversity, and geographic distribution over the past 100 million years, as a result of both changing climates and angiosperm diversification.

FIG. 33.16 Ginkgo biloba. (a) The fan-shaped leaves of Ginkgo turn yellow in autumn. (b) The fleshy seeds enclose a large female gametophyte, as in cycads.

Ginkgos have long been cultivated in China, especially near temples, and it is unclear whether any truly natural populations exist in the wild. Today, however, Ginkgo once again is found all over the world, as its ability to tolerate the pollution and other stresses of urban environments has made it a tree of choice for street plantings.