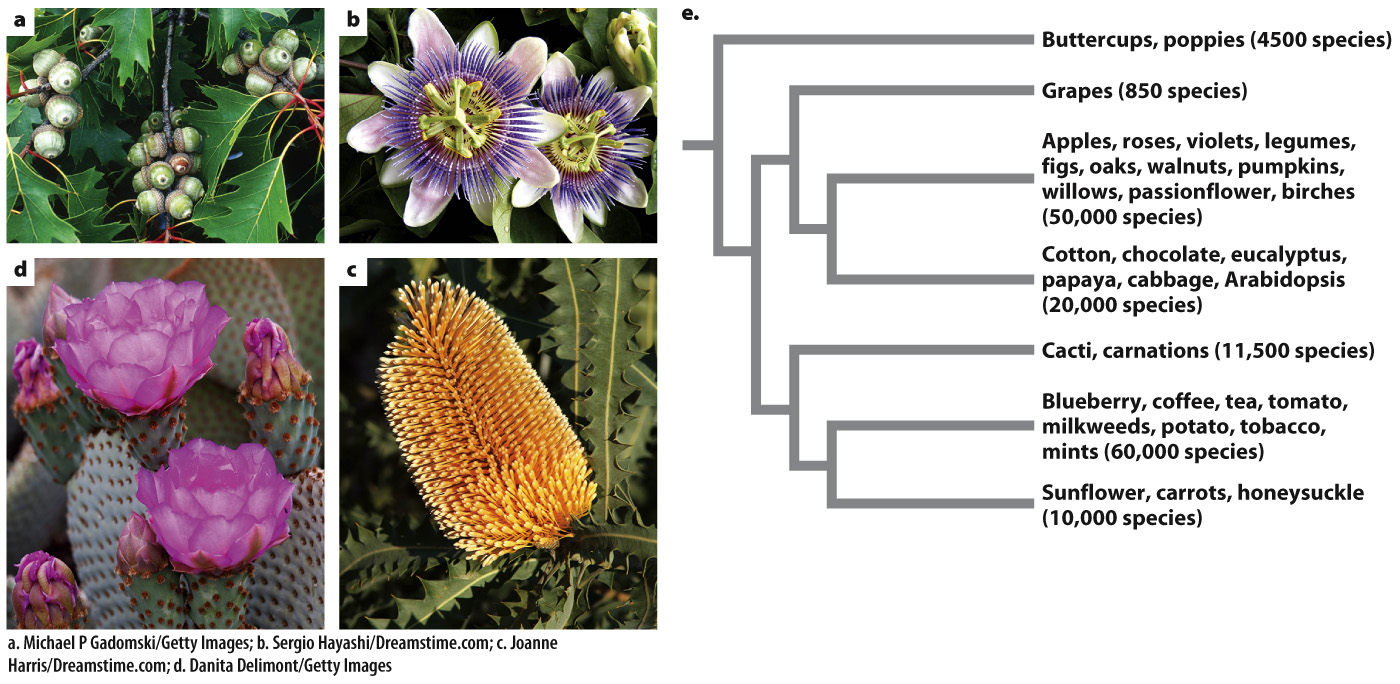

Eudicots are the most diverse group of angiosperms.

Eudicots first appear in the fossil record about 125 million years ago and, by 90 to 80 million years ago, most of the major groups we see today were present. Today, there are estimated to be approximately 160,000 species of eudicots, nearly three-

Many eudicots produce highly conductive xylem. High rates of water transport, and thus high rates of photosynthesis, may explain why eudicot trees were able to replace magnoliid trees as the most ecologically important members of forest canopies. In addition, many eudicot trees lack strong apical dominance and produce crowns with many spreading branches. Today, tropical rain forest trees are an important component of the diversity of eudicots. Important eudicot trees in temperate regions include oaks, willows, and eucalyptus.

At the other end of the size spectrum are the herbaceous eudicots, which make up a substantial fraction of eudicot diversity. Herbaceous plants do not form woody stems. Instead, the aboveground shoot dies back each year rather than withstand a period of drought or cold. At the extreme are annuals, herbaceous plants that complete their life cycle in less than a year, persisting during the unfavorable period as seeds. Annuals are unique to angiosperms and the majority of these annuals are eudicots. Why might eudicots be successful as both trees and herbs? One possibility is that the ability to produce highly conductive xylem may allow herbaceous eudicots to grow quickly and to produce inexpensive and thus easily replaced stems. Examples of herbaceous eudicots include violets, buttercups, and sunflowers.

The herbaceous growth form appears to have evolved many times within eudicots as tropical groups represented by woody plants expanded into temperate regions. For example, the common pea is an herbaceous plant that resides in many vegetable gardens; its relatives include many tropical rain forest trees. Peas are members of the legume, or bean, family, some of which can form symbiotic interactions with nitrogen-

Eudicots are diverse in other ways as well. Most parasitic plants and virtually all carnivorous plants are eudicots, as are water-

The reproduction, growth, and physiology of angiosperms are summarized in Fig. 33.25 on pages 710 and 711.