Case 6: How do fungi threaten global wheat production?

CASE 6 AGRICULTURE: FEEDING A GROWING POPULATION

Throughout much of human history, crops have been vulnerable to infection by Puccinia graminis, the black stem rust of wheat. Puccinia graminis infects wheat leaves and stems through their stomata and then extends within the plant’s living tissues to fuel its own growth. Rust-

734

Many rusts have a life history in which they alternate between different host species. For example, to complete its life cycle, P. graminis must infect wheat first and then barberry bushes (Berberis species). After a particularly severe outbreak of wheat rust during World War I, in which crop losses equaled one-

The Green Revolution seemed to give growers a decisive advantage over stem rust. During World War II, Norman Borlaug, whose original training was in plant pathology, was sent to Mexico by the Rockefeller Foundation to help combat crop losses due to stem rust. Borlaug’s breeding efforts led to resistant wheat varieties. Much of this resistance could be attributed to variation in a small number of genes. Stem rusts were apparently vanquished—

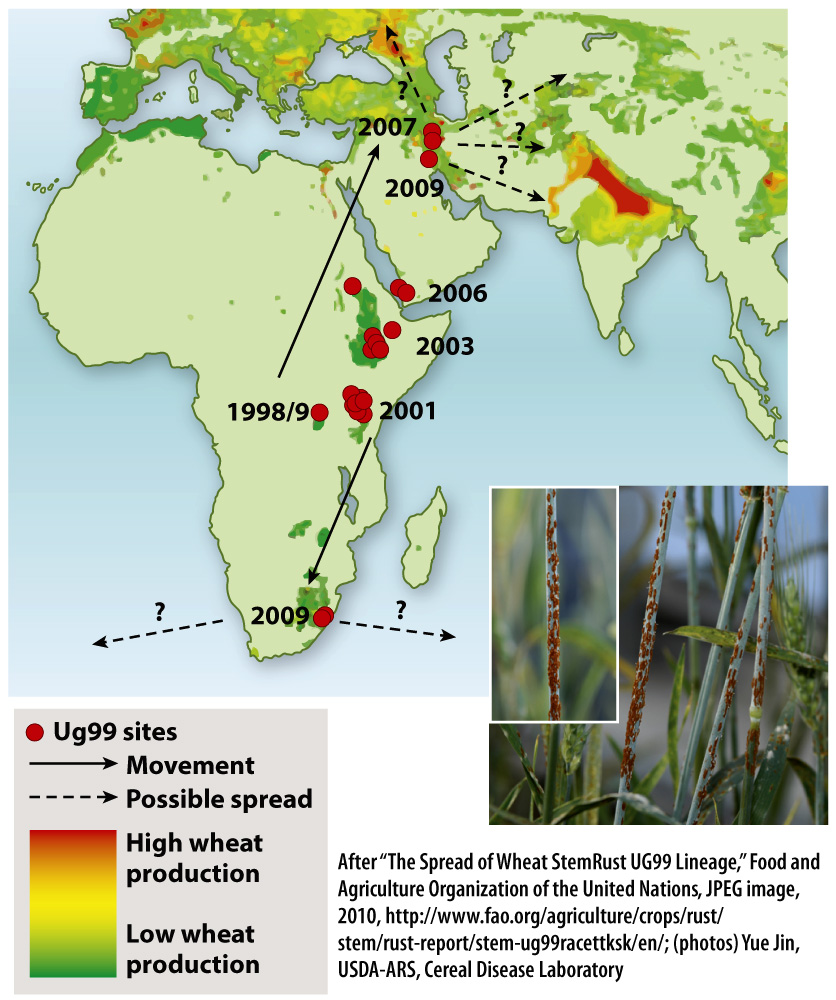

At present, Ug99 shows every sign of spreading (Fig. 34.24)—not surprising given that a single hectare of infected wheat produces upward of a billion spores. It currently devastates wheat production in Kenya and has been found in Yemen (2006), Iran (2007), and South Africa (2009). As you read this, Ug99 is poised to reach the major wheat growing regions of Turkey and South Asia. Even more rapid spread is possible if spores accidentally lodge on cargo or airline passengers.

Just before his death in 2009, Norman Borlaug urged the world to take this threat seriously. Today, plant breeders are actively searching ancestral wheat varieties for genetic sources of resistance to Ug99, while other scientists are trying to understand how plants defend themselves against rusts and what makes Ug99 so virulent. The resurgence of P. graminis as a serious threat to world food production underscores the importance of safeguarding the genetic diversity of agricultural species so that the inevitable evolutionary battles with pathogenic species may be waged successfully.