Fungi are important plant and animal pathogens.

Fungi not only feed on dead plants and animals, but they are also well adapted to infect living tissues (Fig. 34.5). Plants, for example, are vulnerable to a diverse array of fungal pathogens—

Invasion is the key to success for plant pathogens (Chapter 32). Successful pathogens must be able to get past a plant’s physical or chemical defenses. This explains why fungal pathogens exhibit host specificity, meaning that they are able to infect only one or a small number of host species. In many cases, fungi infect plants through wounds, which provide a route through a plant’s outer defenses. Some fungi enter through stomata, while others penetrate epidermal cells directly, degrading the wall with enzymes and then using turgor pressure to push their hyphae into the plant interior. The extent of infection usually depends on the ability of hyphae to expand into new tissues. Vascular wilt fungi (Chapter 32) send their hyphae through xylem vessels, enabling them to spread throughout the entire plant. Old photographs of towns in the eastern United States show streets shaded by American elm trees, but today nearly all those trees are dead, victims of a vascular wilt fungus introduced into the United States early in the twentieth century.

Aboveground, plant infections are usually transmitted by fungal spores, carried either by the wind or on the bodies of insects. For example, many fungi that attack fruits are transmitted by insects also seeking those fruits; yeasts that feed on nectar within flowers hitch rides on pollinators. Some fungi secrete sugar-

Belowground, infection is typically transmitted by hyphae that penetrate the root. Hyphae can feed on organic matter in the soil until they encounter the root of a suitable host plant. The persistence of fungal hyphae in soils means that populations of pathogenic fungi can build up in the soil near a host plant. This is why seedlings germinating close to an adult tree of the same species are at risk of infection, whereas seedlings of distantly related species may be spared. By favoring the establishment of seedlings of less common species, fungal pathogens are thought to play an important role in maintaining high levels of species diversity in tropical rain forests (Chapter 32).

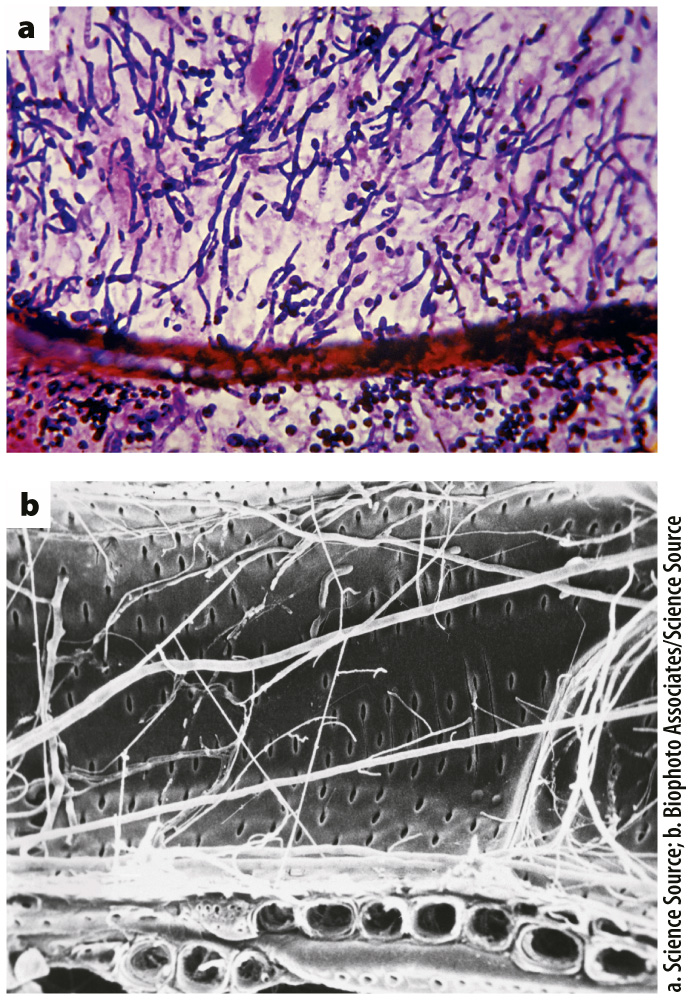

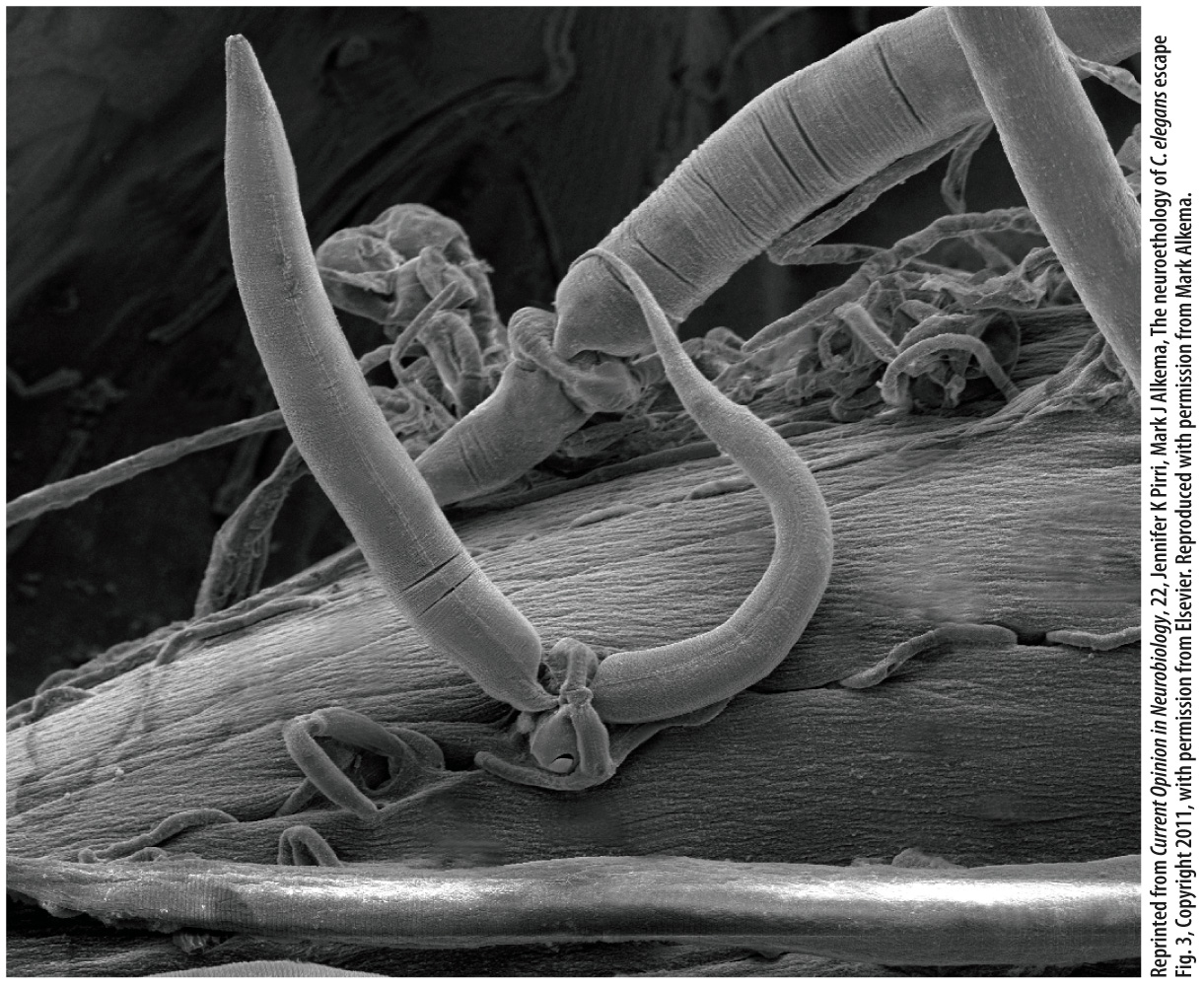

Insects and other invertebrates are also susceptible to fungal pathogens. Certain fungi exploit living animals in a unique way: by trapping them. Some fungal predators form sticky traps with their hyphae, whereas others actually lasso their prey (Fig. 34.6). The hyphae of these fungi form rings that can inflate within seconds, trapping anything within the ring. Nematodes, tiny worms common in soils, inadvertently pass through the rings, setting off hyphal inflation. The nematodes are then trapped, providing food for the fungus.

Fungal infection is relatively rare in vertebrates. Severe infections are more frequent among fish and amphibians than in mammals, perhaps because fungi grow poorly at mammalian body temperatures. An apparent exception is the fungal infection that has caused dramatic declines in North American bat populations. But these fungi infect the bats during their winter hibernation, when the bats have lowered body temperatures that conserve energy. In humans, most fungal infections are annoying rather than life threatening—