Peripheral nervous systems have voluntary and involuntary components.

As bodies with distinct internal organ systems evolved, two separate components of the nervous system emerged. When a gazelle senses a predator, some nerve circuits send a signal to run, an action that is under conscious control, while others signal the heart to beat faster and blood vessels supplying muscles to dilate, actions that occur unconsciously. Conscious reactions are under the control of the voluntary component of the nervous system, and unconscious ones are under the control of the involuntary component. Voluntary components mainly handle sensing and responding to external stimuli, whereas involuntary components typically regulate internal bodily functions. Both nervous system components are found in invertebrate and vertebrate animals.

In insects and crustaceans, for example, nerve circuits from the involuntary component regulate the animal’s digestive system. Nerve circuits connecting sensory structures such as the antennae and eyes to the animal’s brain and muscles are part of the voluntary system.

In vertebrates, the peripheral nervous system is divided into somatic (voluntary) and autonomic (involuntary or visceral) components. The somatic nervous system is made up of sensory neurons that respond to external stimuli and motor neurons that synapse with voluntary muscles. This system is considered voluntary because it is under conscious control. However, many reflexes are controlled lower in the spinal cord (discussed in the following section) or by the brainstem, independent of conscious control by the central nervous system.

756

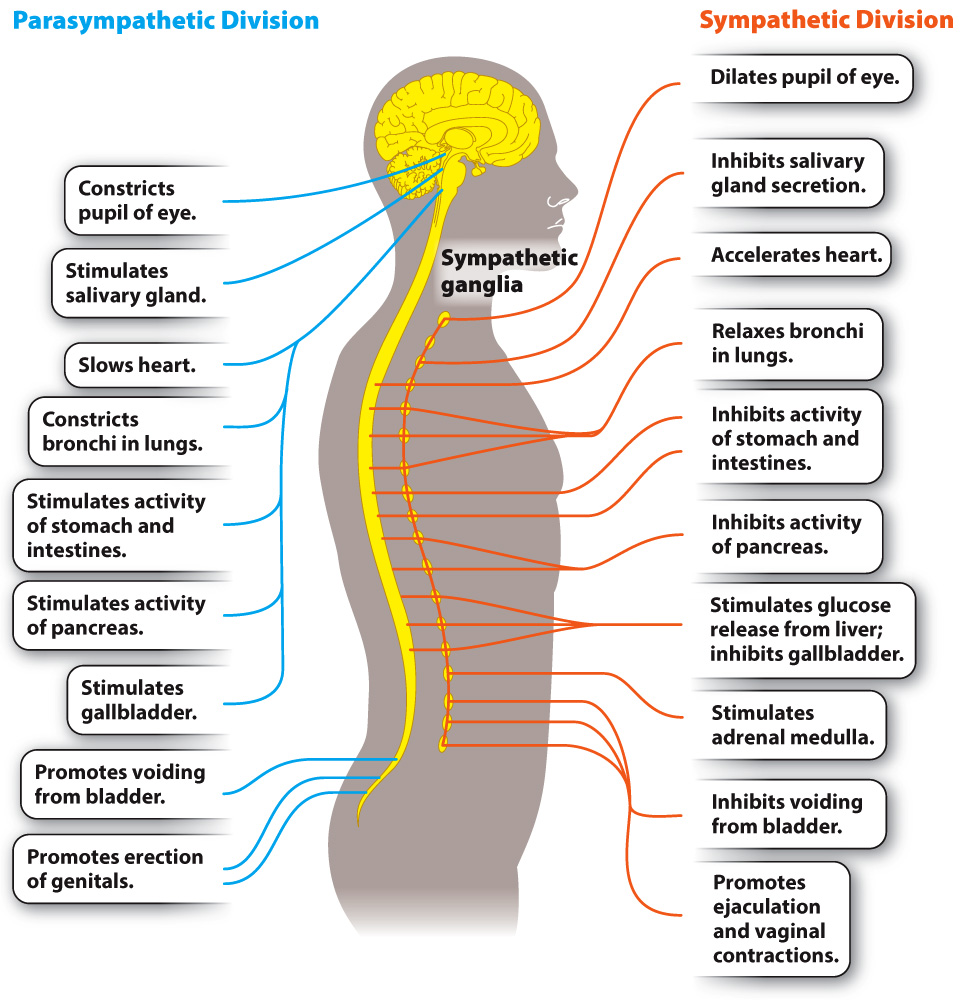

The autonomic nervous system (Fig. 35.17) controls internal functions of the body such as heart rate, blood flow, digestion, excretion, and temperature. It includes both sensory and motor components, which usually act without our conscious awareness. The autonomic nervous system, in turn, is divided into two major subdivisions, a sympathetic division and a parasympathetic division. Both divisions continuously monitor and regulate internal functions of the body. Generally, sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves have opposite effects, but not always. For example, sympathetic neurons stimulate the heart to beat faster, whereas parasympathetic neurons cause the heart to beat slower.

The sympathetic nervous system generally results in arousal and increased activity. It is the pathway activated when animals are exposed to threatening conditions, resulting in what is referred to as the “fight or flight” response. As part of this response, the sympathetic nervous system increases heart rate and breathing rate, stimulates glucose release by the liver, and inhibits digestion. The parasympathetic nervous system, in contrast, slows the heart and stimulates digestion as well as metabolic processes that store energy—

In addition to having different functions, sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves also have different anatomical distributions, as shown in Fig. 35.17. Sympathetic nerves leave the CNS from the middle (thoracic and lumbar) region of the spinal cord, forming ganglia along much of the length of the spinal cord. Parasympathetic nerves leave the CNS from the brain by cranial nerves and from lower (sacral) levels of the spinal cord.