36.1 Animal Sensory Systems

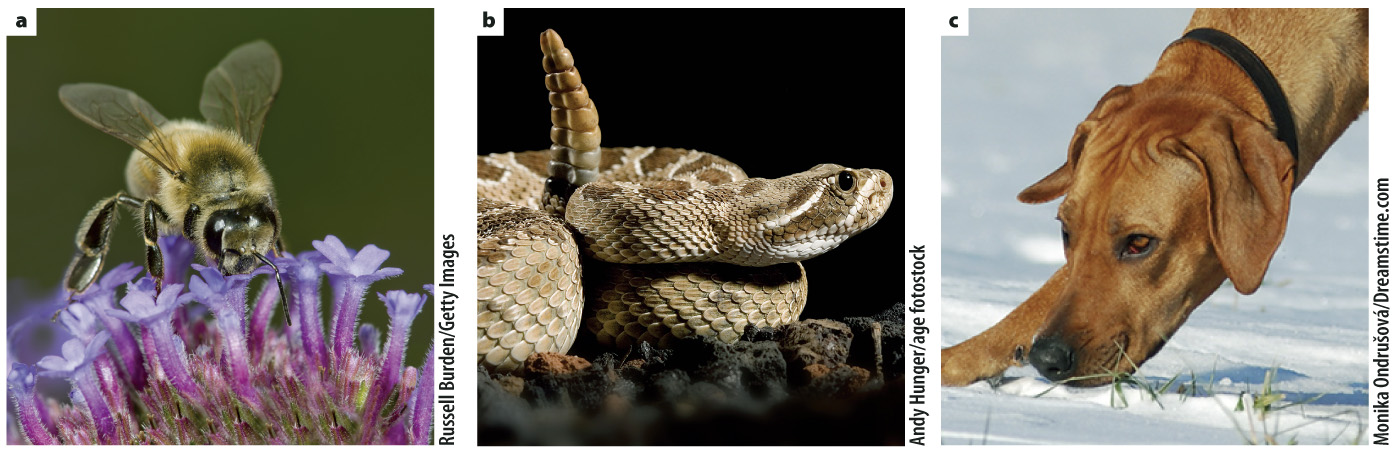

Animals can sense the physical properties of their environment, including light, chemicals, temperature, pressure, and sound, that are useful in finding mates and food and avoiding predators and noxious environments. Early in evolutionary history, organisms evolved specialized protein receptors located in the cell membrane that were able to detect these critical features in their environment. For example, before the evolution of nerve cells and a nervous system, bacteria evolved membrane receptors that sensed osmotic pressures that might otherwise rupture their cell membrane. Bacteria and sponges also evolved membrane receptors that detect chemicals—

The senses of smell, taste, and sight in multicellular organisms with a nervous system also rely on membrane receptors. These receptors are embedded in specialized sensory receptor cells. These cells either communicate with neurons, as for taste and sight, or are themselves neurons, as for smell. Note that the short-

Sensory receptors represent a key cellular unit of the sensory component of animal nervous systems. In most multicellular animals, the sensory receptors are organized into specialized sensory organs that convert particular physical and chemical stimuli into signals that are communicated to the brain. Cnidarians (including jellyfish, corals, and anemones) and roundworms (including the laboratory organism Caenorhabditis elegans) evolved sensory receptors that sensed physical contact, and cnidarians and flatworms were among the first multicellular animals to evolve simple light-

The conversion of physical or chemical stimuli into nerve impulses is called sensory transduction. For example, receptors located in the ear convert the energy of sound waves into nerve impulses that allow an animal to distinguish loud versus soft sounds and high-