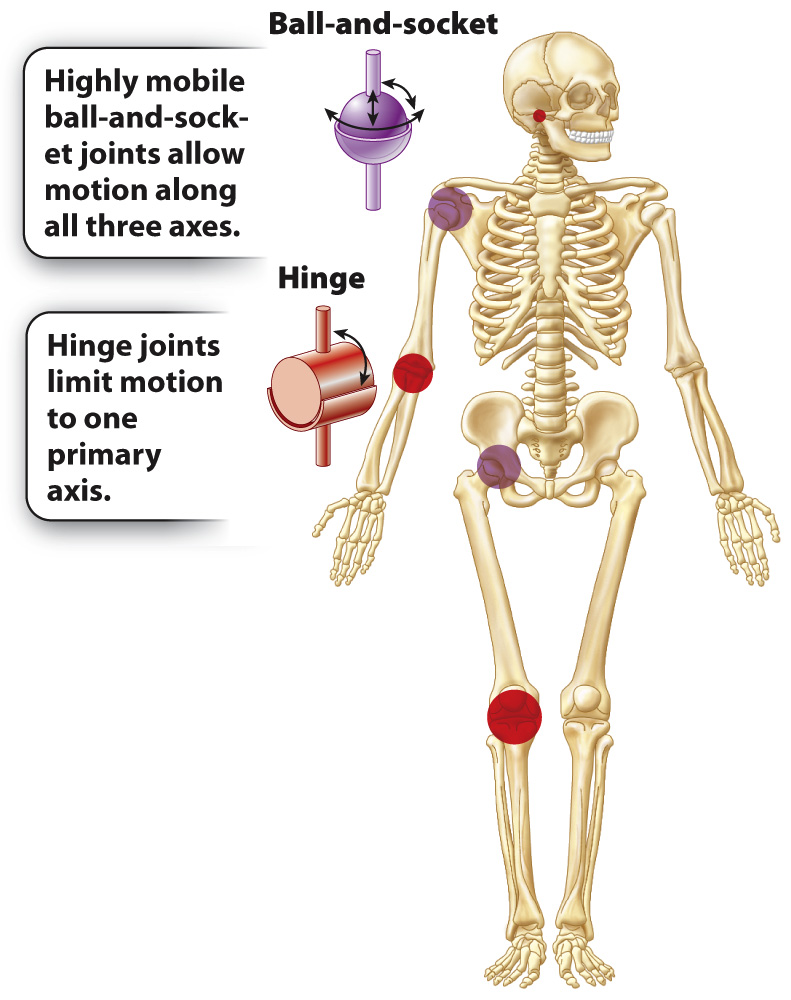

Joint shape determines range of motion and skeletal muscle organization.

The shapes of the bone surfaces that meet at a joint determine the range of motion at that joint. Joints range from simple hinge joints that allow one axis of rotation to ball-

Joints with a broader range of motion are generally less stable. The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body, but it is also the most often dislocated or injured. In contrast, the ankle joint of dogs, horses, and other animals is a stable hinge joint that is unlikely to be dislocated, but its range of motion is limited to flexion and extension. Because muscles are arranged as paired sets of antagonists to move a joint in opposing directions, hinge joints are controlled by as few as two antagonist muscles (generally referred to as a flexor and an extensor). In contrast, ball-