Muscles exert forces by skeletal levers to produce joint motion.

By serving as a rigid set of levers, the skeleton enables muscles to transmit forces that cause joint rotation. Muscles that attach farther from a joint’s axis of rotation produce stronger but slower movements, whereas muscles that attach closer to a joint produce weaker but faster movements. This is why you open a door by pulling on a doorknob located opposite from its hinges. The doorknob’s location increases the lever distance, making it easier to pull the door open than if it were placed next to the hinge.

803

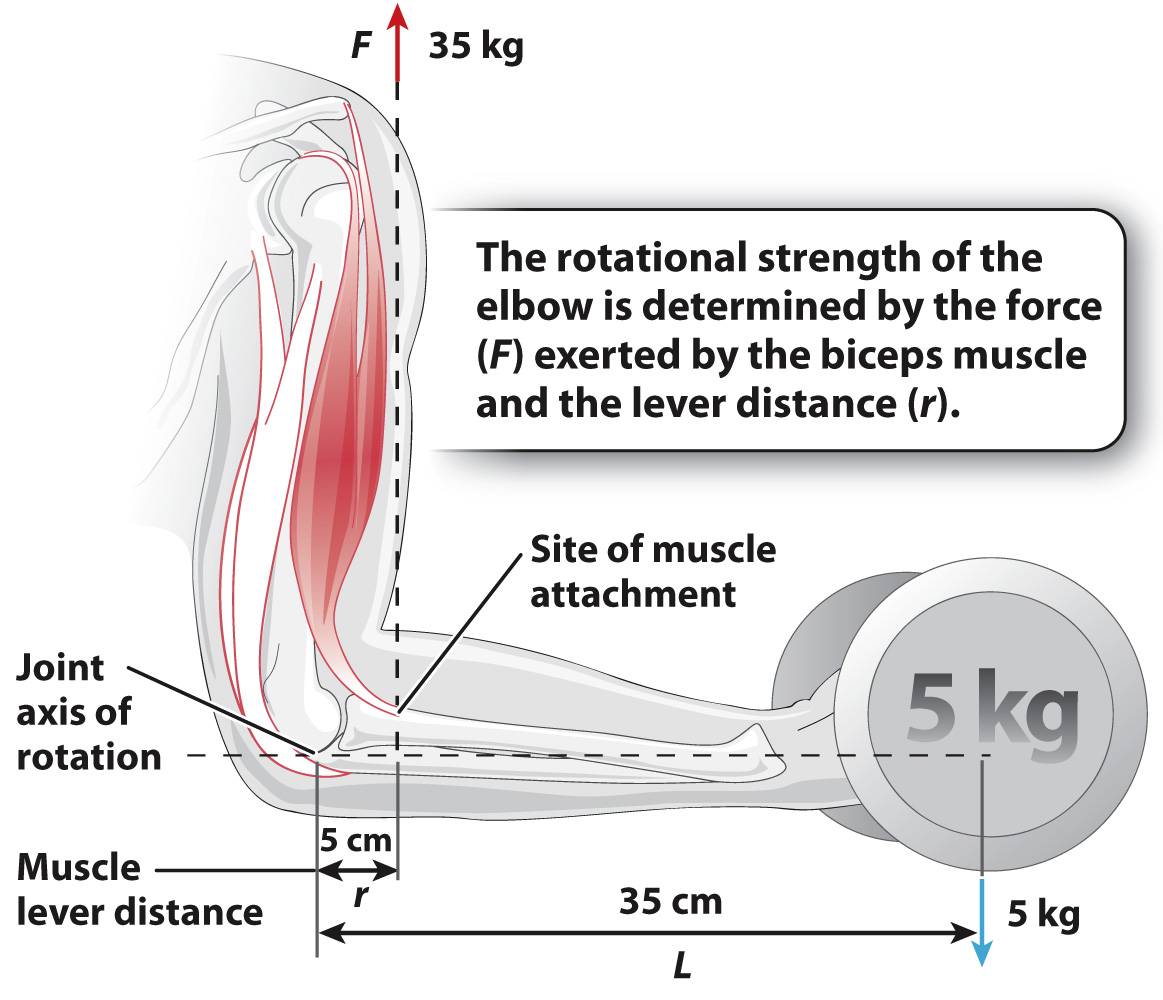

The strength of rotational movement, or torque, is determined by the product of a muscle’s force (F) and lever distance (r) from the axis of joint rotation: F × r. Therefore, muscles produce stronger rotational movements either by exerting a larger force or by having a longer lever distance between the joint and muscle attachment site. Let’s consider a simple example: a weight carried by your hand (Fig. 37.21). In this case, the axis of rotation is the elbow, and contraction of the biceps muscle causes the arm to flex at the elbow. The strength of elbow rotation is determined by the biceps muscle’s force (F) and the lever distance (r) between the elbow joint and the site of muscle attachment, where the muscle pulls on the arm bone.

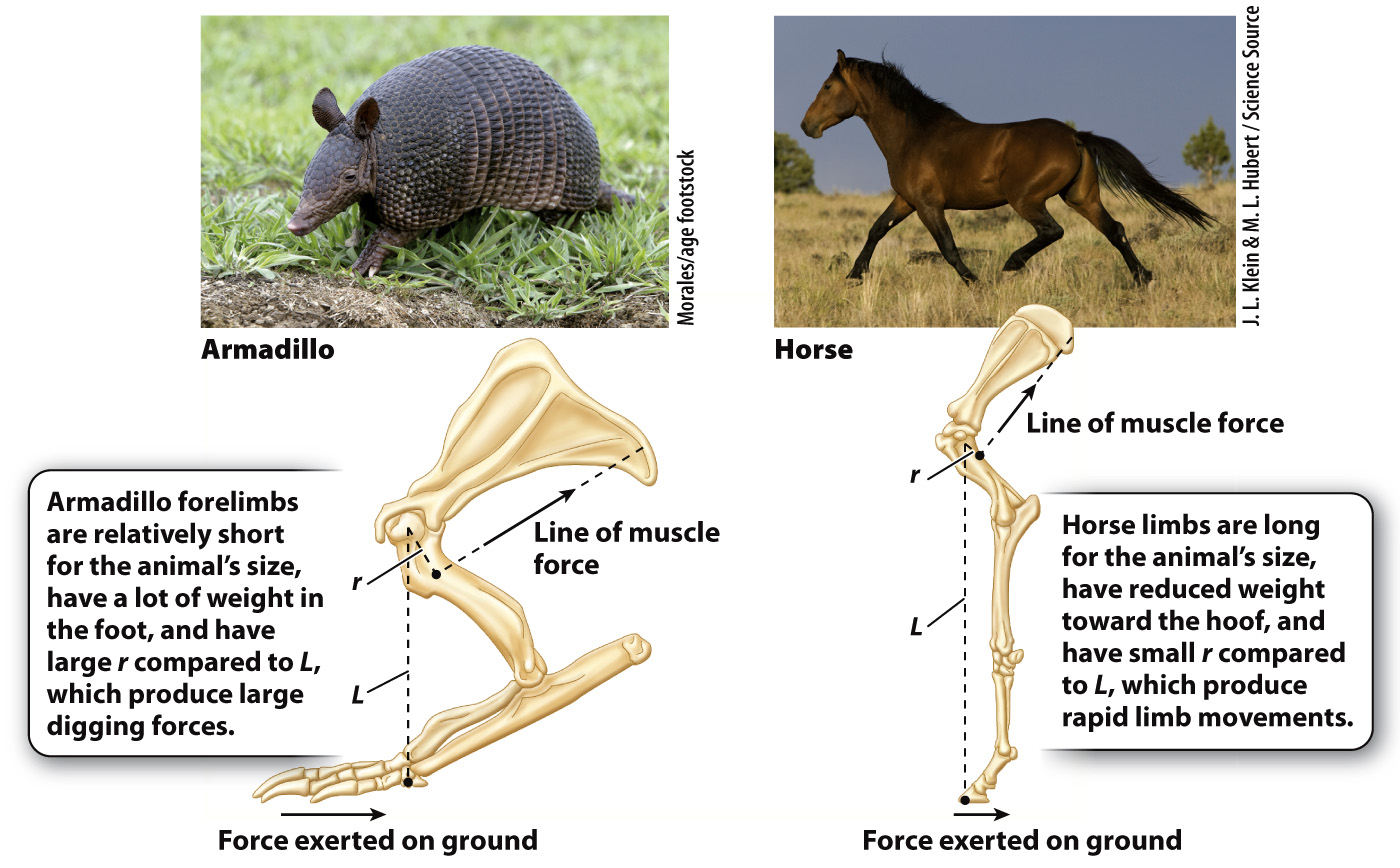

In addition to the muscle’s force (F) and lever distance (r), the distance from the joint to the site where the force is exerted (L) also affects movement (Fig. 37.21, Fig. 37.22). Animal joints located a long distance from the muscle attachment site (large r) and a short distance from where the output force is exerted (small L) produce strong but slow movements. Moles, armadillos, and spade-

804