Final digestion and nutrient absorption take place in the small intestine.

After the food enters the small intestine, final digestion of protein, carbohydrates, and fats occurs. The nutrients released by digestion then are absorbed by the body. Finally, the acid produced by the stomach is neutralized to create an environment for the intestinal enzymes to act. These functions are carried out by the small intestine with the help of two other organs, the pancreas and liver (Fig. 40.15).

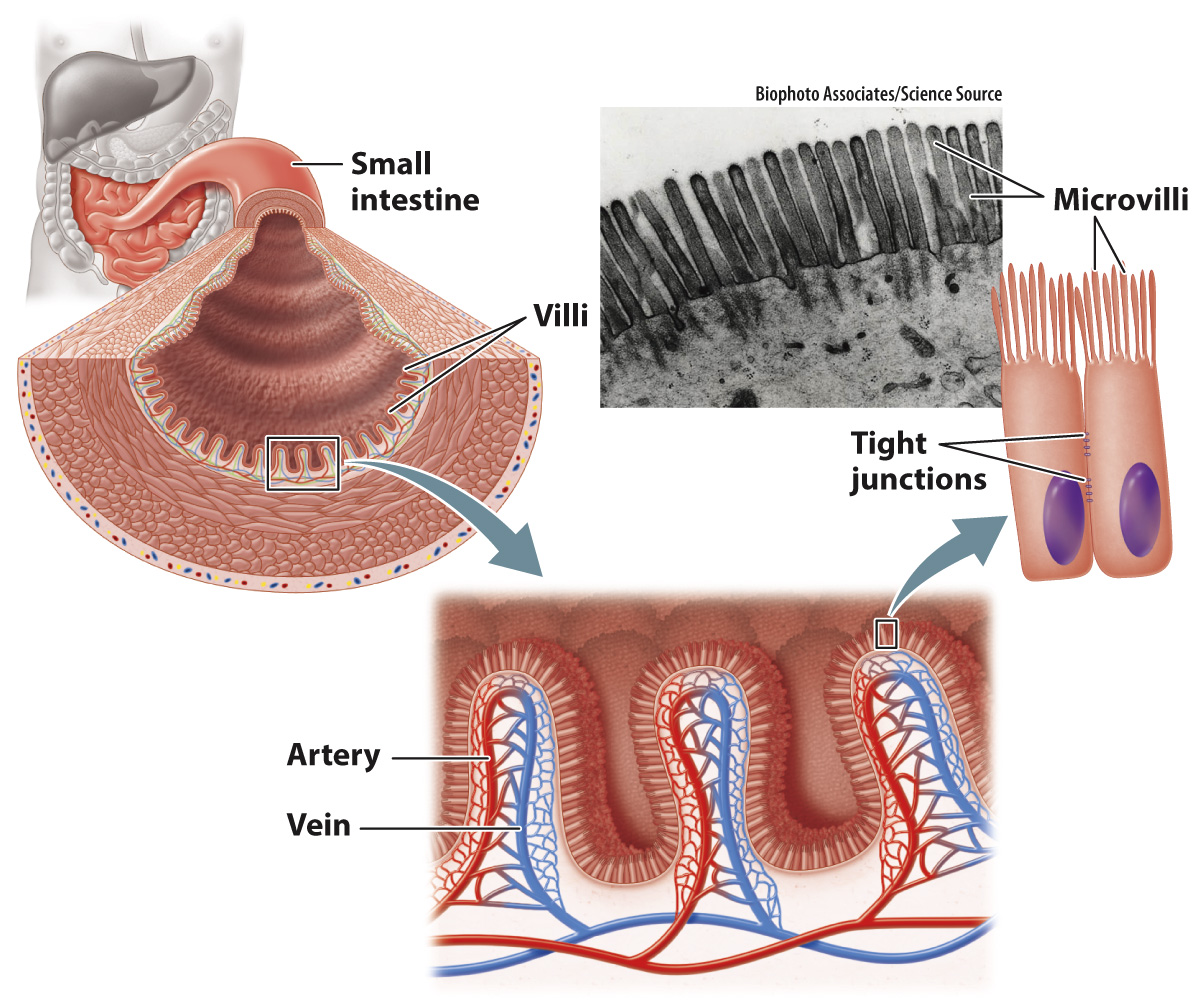

The small intestine is so named because of its small diameter, but it is a long (about 20 feet or 6 m in an adult human) and therefore a large organ. Because of its length, the small intestine is coiled to fit within the abdominal cavity. The small intestine is made up of three sections (see Fig. 40.15, upper right). The initial section is the duodenum, into which the food enters from the stomach. Most of the remaining digestion takes place in the duodenum, and nutrient absorption takes place in the duodenum as well as in the next two sections, the jejunum and ileum.

867

Some digestive enzymes are produced by the small intestine. For example, cells of the small intestine produce lactase, an enzyme that breaks down the sugar lactose into glucose and galactose (Table 40.3). Lactose is found in milk, and so lactase is important in newborn mammals during suckling. In humans, the gene that encodes lactase has an interesting evolutionary history. Some people cannot drink milk as adults, a condition called lactose intolerance. In these individuals, the gene that encodes lactase is down-

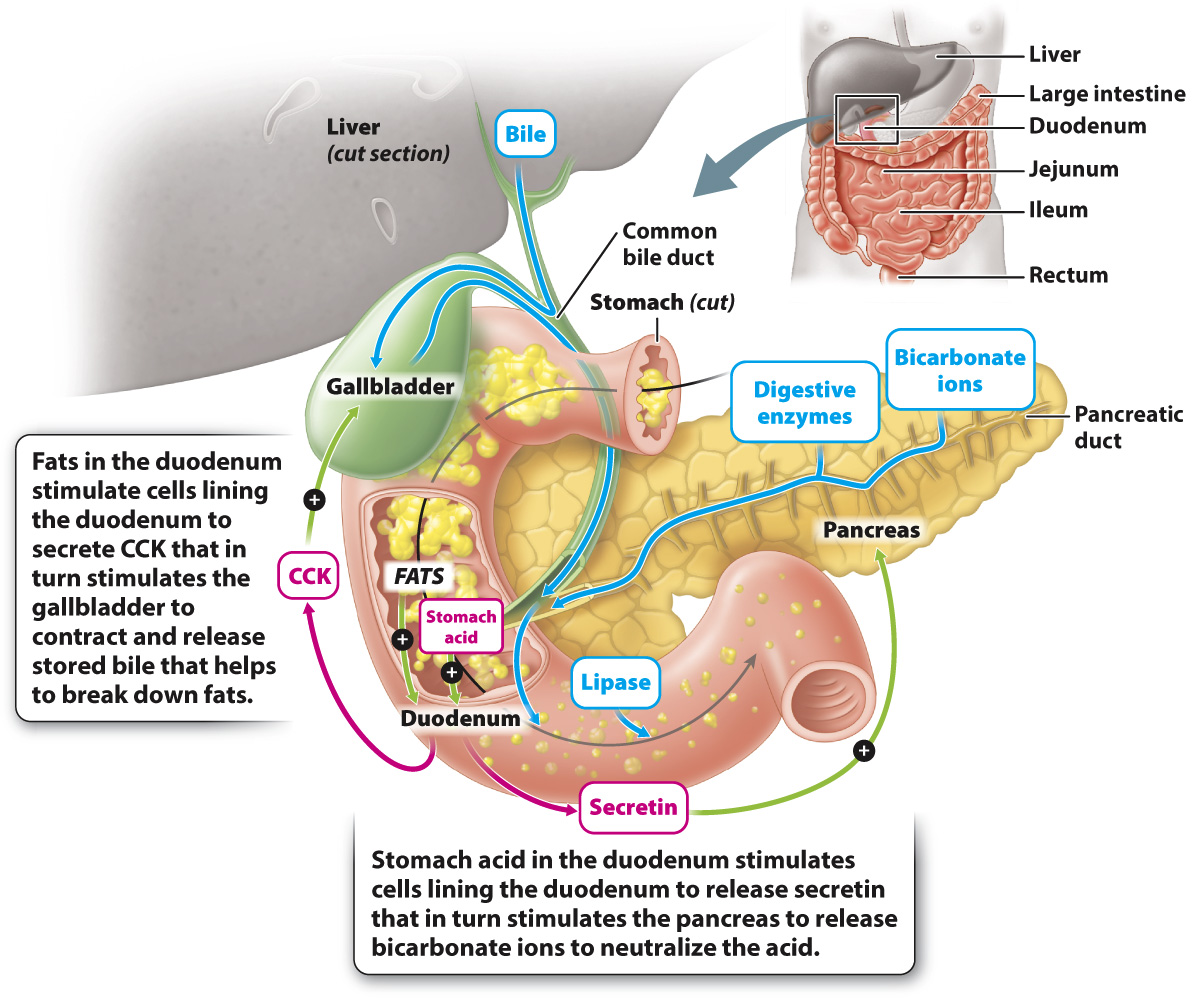

Many of the digestive enzymes that act in the small intestine are not produced by the small intestine, but instead by the pancreas. The pancreas is an organ that lies below the stomach, behind the duodenum (Fig. 40.15). It secretes hormones directly into the blood, as discussed in Chapter 38, and secretes other substances into ducts that connect to the duodenum. The pancreas produces a variety of digestive enzymes, including lipase, which breaks down fats; amylase, which breaks down carbohydrates; and trypsin, which breaks down proteins (Table 40.3). Like pepsin produced by the stomach, the pancreas produces trypsin in an inactive form called trypsinogen to avoid digesting itself. Trypsinogen is converted to trypsin by an enzyme produced by intestinal cells.

The pancreas also secretes bicarbonate ions, which neutralize the acid produced by the stomach. The pancreas is stimulated to secrete bicarbonate ions by the hormone secretin (the first hormone to be identified). Cells lining the duodenum secrete the hormone in response to the acidic pH of the stomach contents entering the small intestine.

868

The liver participates in digestion by producing bile, which is composed of bile salts, bile acids, and bicarbonate ions. Bile aids in fat digestion by breaking large clusters of fats into smaller lipid droplets, a process called emulsification. Bile produced by the liver is stored in the gallbladder (Fig. 40.15). When fats enter the duodenum, cells lining the duodenum release a peptide hormone called cholecystokinin (CCK), which causes the gallbladder to contract, thus releasing the bile into the duodenum. By breaking up the fats into smaller droplets, bile allows lipases to digest the lipids more effectively.

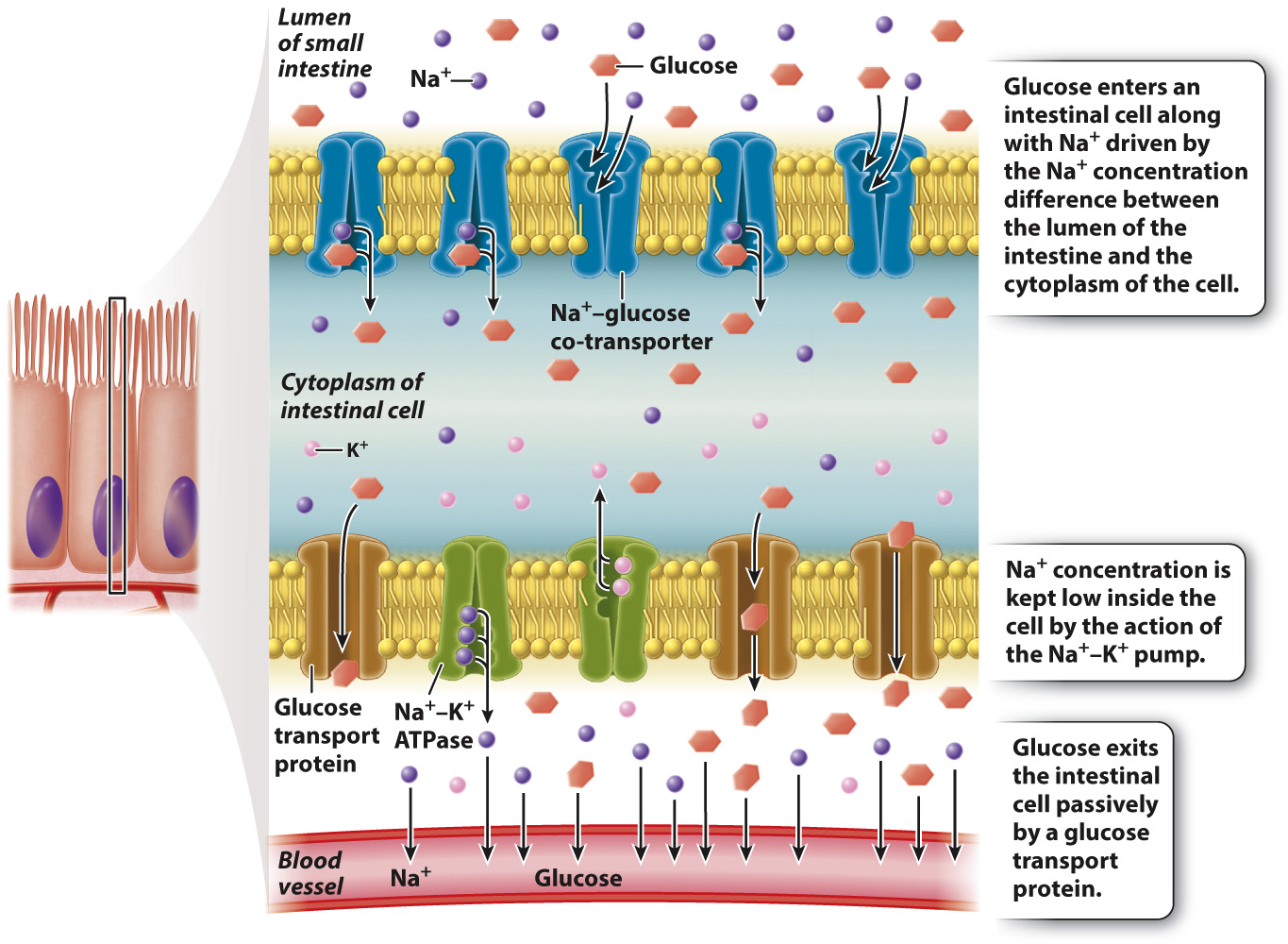

When large macromolecules are broken down by digestive enzymes, they are ready to be absorbed, another function of the small intestine. The small intestine has highly folded inner surfaces, called villi, and the cells constituting the villi themselves have highly folded surfaces, called microvilli (Fig. 40.16). Together, villi and microvilli greatly increase the surface area for the absorption of nutrients. Cells that line the small intestine are connected by tight junctions (Fig. 40.16; Chapter 10). These junctions force the products of digestion to be absorbed across the microvilli surfaces, rather than leaking between the cells. Membrane transporters can then control their movement through the cell and into the bloodstream.

Nutrient molecules, such as glucose and amino acids, are often co-

869