Plant-

Herbivorous (that is, plant-

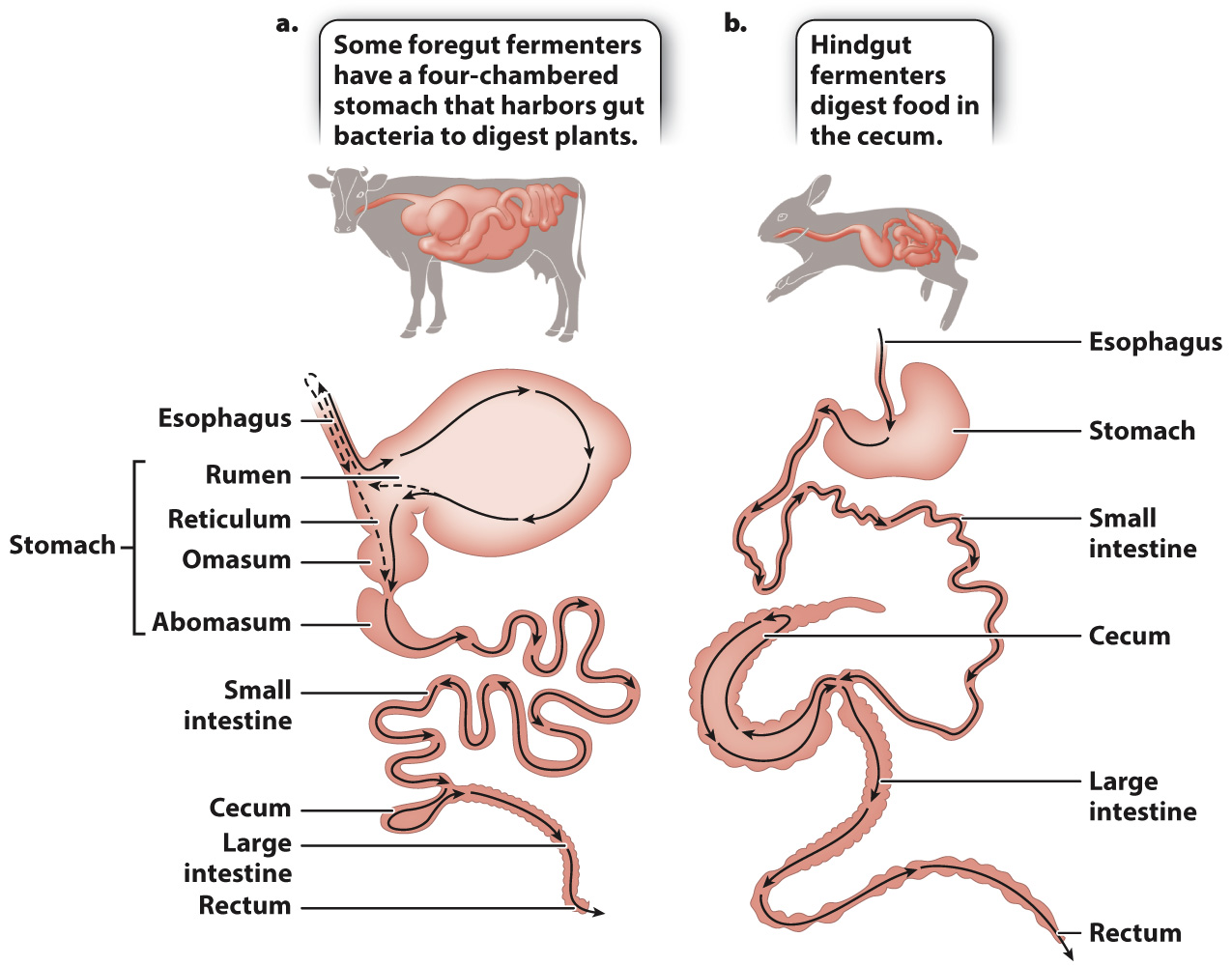

Rather than the single stomach of other mammals, ruminants (cattle, sheep, and goats) have a four-

871

Carbon dioxide and methane gas are also produced as a result of bacterial fermentation. The amount of methane produced by domesticated ruminants is second only to the amount produced industrially. Since methane is a greenhouse gas that traps heat from the sun, methane production by cattle, sheep, and other animals contributes to atmospheric increases in methane and global climate change (Chapter 25).

After leaving the reticulum, the mixture of food and bacteria passes into a third chamber, the omasum, where water is absorbed. It then enters the abomasum, the last of the four chambers, where protein digestion begins as it does in other mammals. The acid and protease secretions kill the bacteria, and the nutrients are absorbed in the small intestine. The bacteria, too, are an important protein source for the ruminant, yielding as much as 100 g of protein each day for the cow. This is important because plants are a poor source of protein but contain considerable nitrogen that the bacteria use to synthesize their own amino acids. The bacteria lost to digestion are balanced by the continual reproduction of bacteria in the rumen.

In contrast to the foregut fermentation of cows and sheep, other mammalian herbivores, such as horses, rabbits, and koalas, digest the plant material they eat by hindgut fermentation (Fig. 40.19b). Hindgut fermentation occurs in the colon and in the cecum, a chamber that branches off the large intestine. Because the fermentation products released from the cecum have already passed through the small intestine, the main site of nutrient absorption, hindgut fermentation is a less efficient nutrient extractor than foregut fermentation.

In humans and other animals such as lemurs and squirrels, the cecum is present but small and includes the appendix, a narrow, tubelike structure that extends from the cecum. The appendix is an example of a vestigial structure, a structure that has lost its original function over time and is now much reduced in size. Although the appendix has no clear function in nonherbivorous animals, evidence suggests it may play a role in the immune system (Chapter 43). The appendix can become infected when partially digested material enters or blocks it. Unless the infected appendix is removed, it can burst, releasing gut contents into the abdominal cavity, a condition that can be life threatening.

872

Charles Darwin put forth a hypothesis explaining how the appendix might have evolved to take on its current form in humans. He suggested that in the ancestors of modern humans the cecum harbored bacteria that aided in the digestion of plant material such as cellulose. However, as their diet became less reliant on plant material, the cecum became smaller and lost its function over time, becoming what we see today as the appendix. Vestigial structures, such as the appendix in humans, remnants of hind limbs in whales, small eyes in cave-

Quick Check 5 Some animals, such as rabbits, whose digestive systems include hindgut fermentation, re-

Quick Check 5 Answer

By eating the products of the cecum, these animals can pass the partially digested food by the small intestine a second time, where nutrients are then absorbed.