Metabolic rate is linked to body temperature.

Metabolic rate is also affected by an animal’s internal body temperature. Temperature affects the rates of chemical reactions, which in turn determine how fast fuel molecules can be mobilized and broken down to supply energy for a cell. Animals can be categorized by the sources of most of their heat. Animals that produce most of their own heat as by-

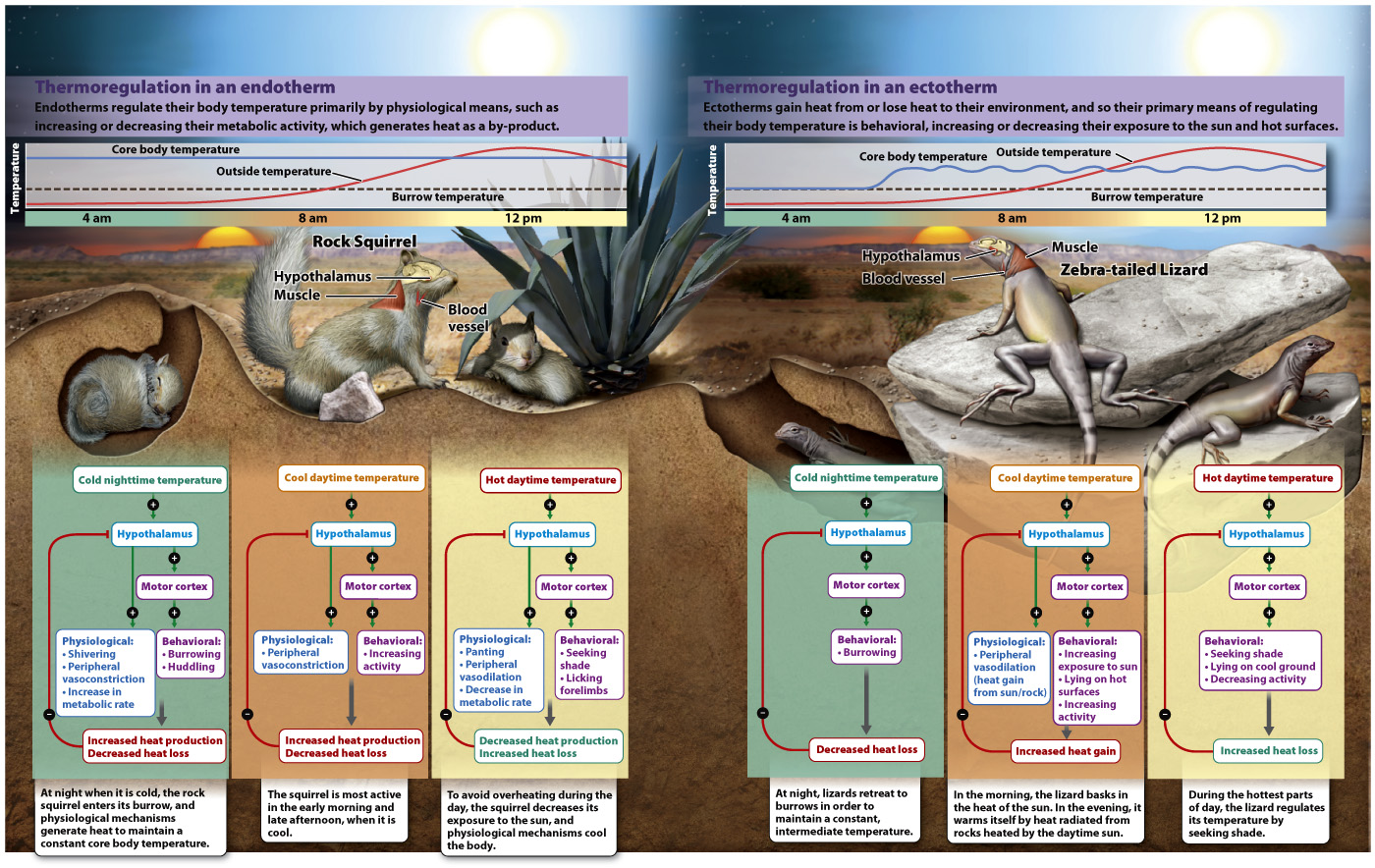

By contrast, animals that obtain most of their heat from the environment are ectotherms. Ectotherms often regulate their body temperatures by changing their behavior—

Endotherms are sometimes referred to as “warm-

856

Nevertheless, thermoregulatory mechanisms have profound implications for an animal’s metabolic rate. Endotherms have a higher metabolic rate than ectotherms. As a result, they are able to be active over a broader range of external temperatures than ectotherms. Both the activity level and metabolic rate of ectotherms increase with increasing body temperature. However, ectotherms have metabolic rates that are about 25% of endotherms of similar body mass and at similar body temperatures. Although they can achieve activity levels similar to those of endotherms when their body temperatures are similar, ectotherms cannot sustain prolonged activity. Therefore, ectotherms such as lizards or insects rely on brief bouts of activity, followed by longer periods of inactivity compared to endotherms.

857

Endotherms benefit from having an active lifestyle. However, their high metabolic rate requires long periods of foraging to acquire enough food to keep warm and be active. By contrast, although ectotherms cannot sustain activity for long periods, they can survive much longer periods without food.

As we have discussed, the control of core body temperature, or thermoregulation, is a form of homeostasis and requires the coordinated activities of the nervous, muscular, endocrine, circulatory, and digestive systems. We summarize how these systems work together in endotherms and ectotherms in Fig. 40.5.

VISUAL SYNTHESIS