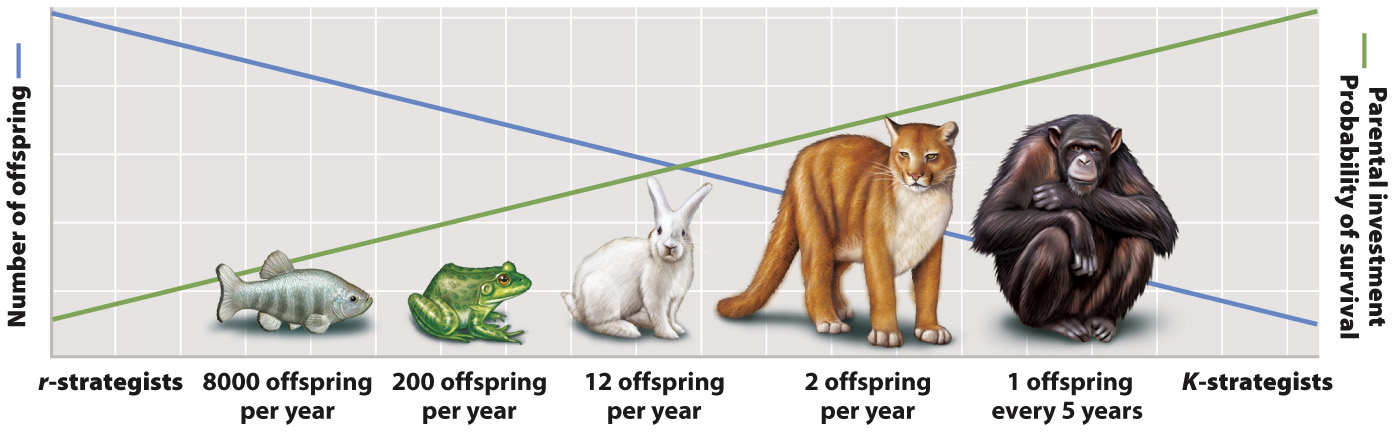

r-strategists and K-strategists differ in number of offspring and parental care.

While the terms “external” and “internal” fertilization focus our attention on where fertilization takes place, the two modes of reproduction are associated with a host of other behavioral and reproductive differences. One key difference is the number of offspring produced.

External fertilization is generally associated with the release of large numbers of gametes and the production of large numbers of offspring, each of which has a low probability of survival in part because the offspring typically receive little, if any, parental care. External fertilization, in other words, is a game of numbers. For internal fertilization, however, there is much more control over fertilization and subsequent development of the embryo because both fertilization and embryonic development take place inside the female. As a result, animals that use internal fertilization typically produce far fewer offspring and invest considerable time and energy into raising those offspring.

These two strategies represent two ends of a continuum of reproductive strategies that was first described by the American ecologists Robert H. MacArthur and E. O. Wilson in 1967. Organisms that produce large numbers of offspring without a lot of parental investment are r-

According to this model, the environment places selective pressures on organisms to drive them in one or the other direction. In general, r-

These two strategies represent the extremes of a spectrum, and there are notable exceptions. An octopus, for example, can lay up to 150,000 eggs, typical of r-