B cells produce antibodies.

One of the hallmarks of adaptive immunity is the ability to target specific novel pathogens. But there are many different viruses, bacteria, single-

An antibody is a large protein found on the surface of B cells or free in the blood or tissues. An antibody binds to molecules on the surface of foreign cells, called antigens, which, by definition, are molecules that lead to the production of antibodies. (The word “antigen” is a contraction of “antibody” and “generator.”) Any molecule that naturally occurs on or in a microorganism can be an antigen. The great diversity of antigens on different microorganisms is matched by a great diversity of antibodies produced by an individual. It is estimated that humans produce approximately 10 billion different antibodies, each with the ability to recognize one or a few antigens on microorganisms.

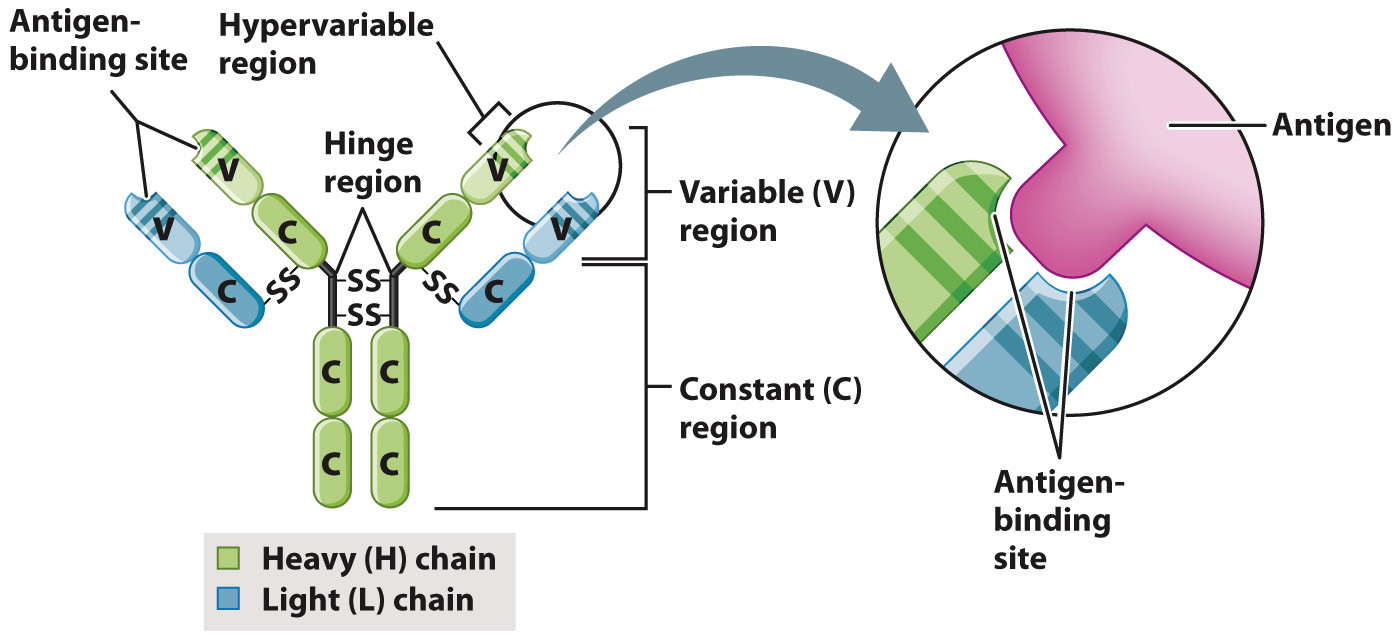

Antibodies have a distinctive structure that reflects their specificity for a given antigen. The simplest antibody molecule, shown in Fig. 43.9, is a Y-

The light and heavy chains are both subdivided into variable (V) and constant (C) regions (Fig. 43.9). The constant region, as the name implies, is the same in all antibodies of a given class. The variable region is unique to each antigen that the antibody targets. Within the variable regions of the L and H chains are regions that are even more variable, called hypervariable regions. These hypervariable regions interact in a specific manner with just a portion of the antigen.

Binding of antibodies to antigens is the first step in recognition and removal of pathogens. Binding alone is sometimes enough to disable a pathogen. More often, the pathogen is killed by a different component of the immune system, for example by a phagocyte or the complement system. In this case, the function of an antibody is to recognize the pathogen, then recruit other cells of the immune system or activate the complement system.