The ability to distinguish between self and nonself is acquired during T cell maturation.

936

Of all the possible T cell receptors that are generated by genomic rearrangement, only some are useful. Useful T cell receptors must be able to react with the host’s own MHC proteins. In addition, useful T cell receptors must not react with other molecules that are normally present in or on cells of the host. In other words, T cells must respond only to self MHC proteins in association with nonself antigens, but not to other self molecules of an organism’s own cells.

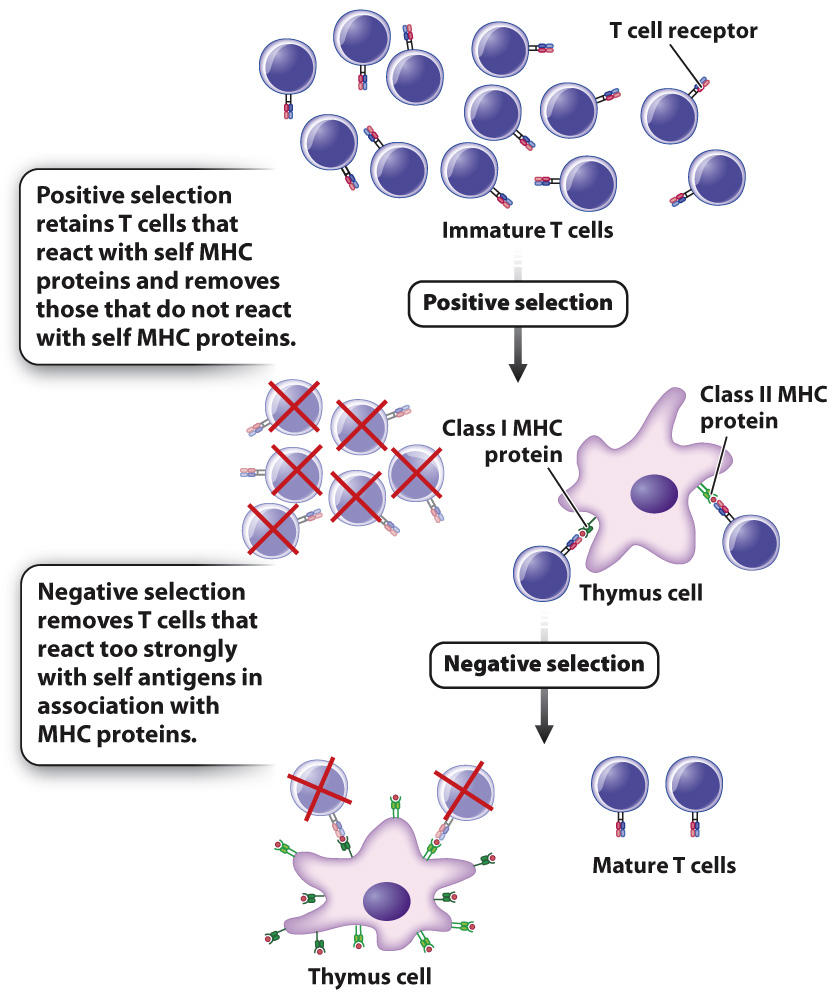

A sorting process is therefore necessary so that only some T cells mature and others are eliminated (Fig. 43.17). As T cells mature in the thymus, they interact with cells of the epithelium of the thymus. The T cells that recognize self MHC proteins on epithelium cells are positively selected and continue to mature. The T cells that react too strongly to self antigens in association with MHC are negatively selected and eliminated through cell death. Note that, in spite of their names, both processes involve the elimination of some T cells.

The result of this sorting process is twofold. First, T cells become MHC restricted, meaning that they interact only with antigens that are associated with MHC proteins (helper T cells with antigen plus MHC class II proteins, and cytotoxic T cells with antigen plus MHC class I proteins). Second, T cells exhibit tolerance—in other words, they do not respond to self antigens, even though the immune system functions normally otherwise. Those antigens present as T cells mature are identified as self and do not elicit a response; those not present are nonself and, if encountered, do elicit a response.

B cells also exhibit tolerance to self antigens because they go through a similar process of negative selection in the bone marrow. During that process, B cells that react strongly to self antigens are eliminated through cell death. Although most self-

The ability to distinguish self from nonself is critical. Failure leads to autoimmune disease, in which tolerance is lost and the immune system becomes active against antigens of the host. Autoimmune diseases can be debilitating as T cells or antibodies attack cells and organs of the host. In rheumatoid arthritis, self-