White blood cells provide a second line of defense against pathogens.

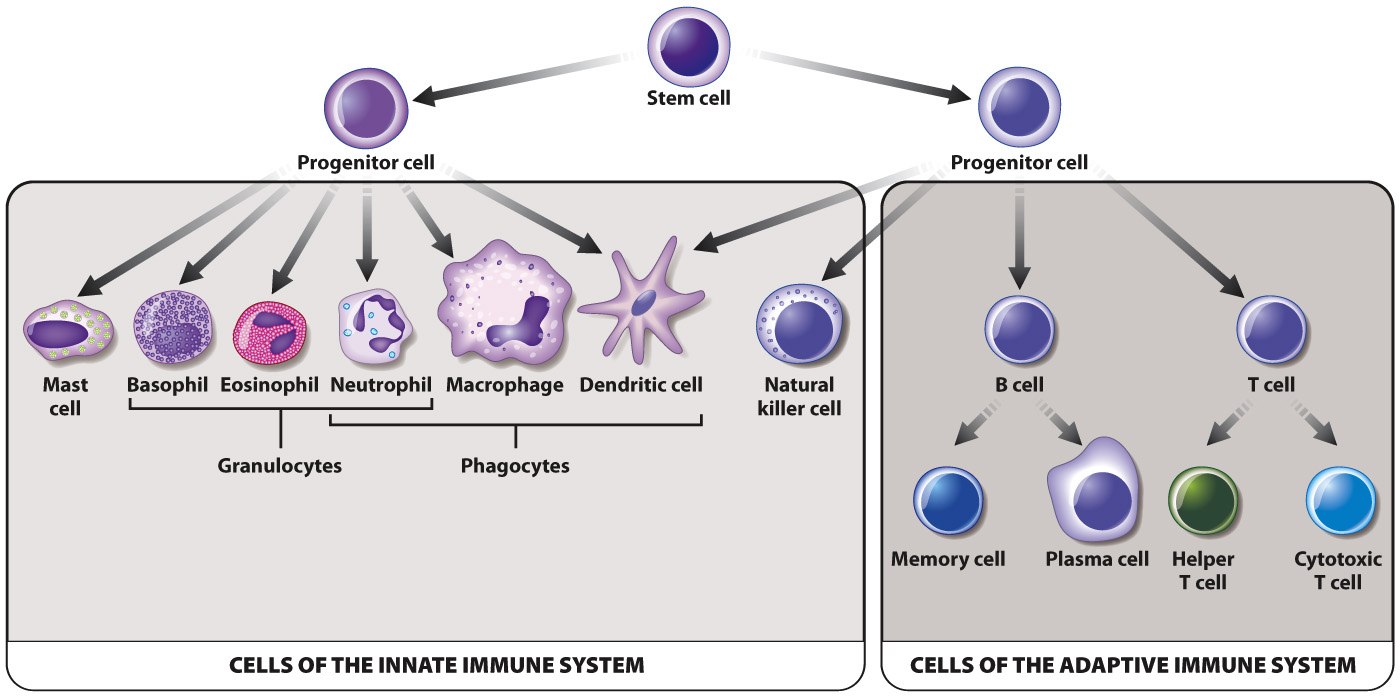

If a pathogen makes it past the skin and mucous membranes of an animal, there is a second line of defense: white blood cells (leukocytes). There are many different types of white blood cell, which arise by differentiation from stem cells in the bone marrow (Fig. 43.3). Just as the skin and mucous membranes are an external defense against pathogens, white blood cells are an internal defense. Some white blood cells mount an early response to a pathogen; these are nonspecific innate immune cells. If they are unable to clear the pathogen, they alert the more specialized white blood cells of the adaptive immune system. Here, we focus on the role of white blood cells in innate immunity.

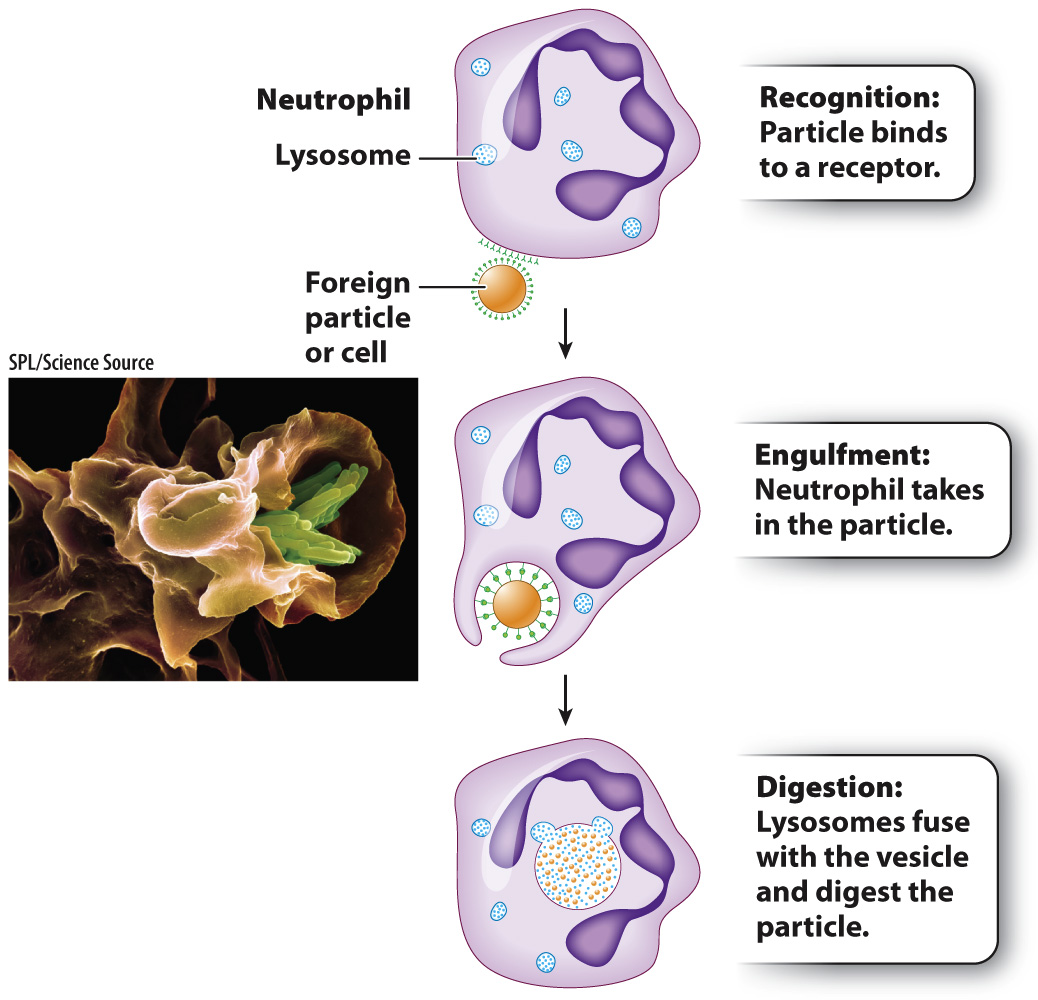

Phagocytes (literally, “eating cells”) are white blood cells that engulf and destroy foreign cells or particles. The engulfing of a cell or particle by another cell is called phagocytosis. The Russian microbiologist Ilya Mechnikov first described this remarkable process, for which he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with the German scientist Paul Ehrlich in 1908.

The process begins when a phagocyte encounters a cell or particle that it recognizes as foreign and binds to it. The phagocyte then extends its plasma membrane completely around the cell or particle until it is contained in a compartment or vesicle inside the phagocyte (Fig. 43.4). In some cases, the vesicle merges with a lysosome, and enzymes within the lysosome digest the foreign cell or particle. Phagocytosis can also trigger a respiratory burst, a process that generates reactive oxygen species, such as superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide, and reactive nitrogen species, such as nitrogen oxide and nitrogen dioxide. These molecules have antimicrobial properties that directly damage pathogens.

There are three major types of phagocytic cell: macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils (see Fig. 43.3). In each case, their names give clues to their shape and size. Macrophages are large cells that patrol the body (macro means “large”). Dendritic cells have long cellular projections that resemble the dendrites of neurons (Chapter 35). These cells are typically part of the natural defenses found in the skin and mucous membranes. Neutrophils are members of a group of cells called granulocytes because of the presence of granules in their cytoplasm. The granules of neutrophils take up both acidic and basic dyes, so their staining pattern is considered neutral. Neutrophils are abundant in the blood and are often the first cells to respond to infection.

The innate immune system includes several other white blood cell types in addition to phagocytic cells (see Fig. 43.3). Two types of granulocyte, eosinophils and basophils, defend against parasitic infections, but they also contribute to allergies. Mast cells release histamine, an important contributor to allergic reactions and inflammation. Finally, natural killer cells do not recognize foreign cells, but instead recognize and kill host cells that are infected by a virus or have become cancerous or otherwise abnormal.