Communication is the transfer of information between a sender and receiver.

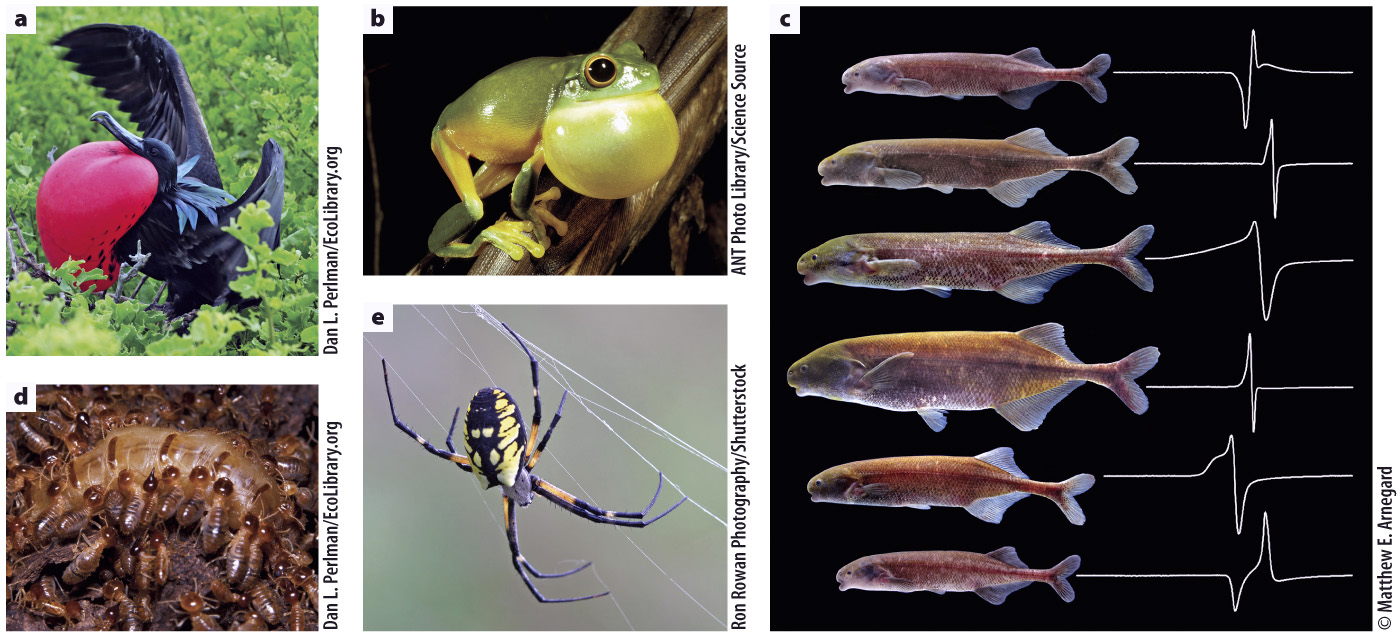

The sophistication of animal communication varies enormously, as can be seen by the variety of types of signal illustrated in Fig. 45.13. Even our closest relatives, the chimpanzees, cannot rival the human facility with language, but a number of species have evolved forms of communication that convey remarkably complex and specific information. For example, a vervet monkey that perceives a threat to its group will utter an alarm call that not only warns of a threat, but actually specifies the nature of the threat—

The simplest definition of communication is the transfer of information between two individuals, the sender and the receiver. The sender supplies a signal that elicits a response from the receiver. For example, the bright petals of a flower signal to an insect that nectar and pollen are available. This definition, however, has its problems. An owl hears the rustling of a mouse and responds accordingly. Most people would agree that the owl is not really communicating with the mouse (nor the mouse with the owl). For this reason, some biologists prefer to define communication as attempts by the sender to manipulate in some way the behavior of the receiver.

How has communication evolved? It is thought that communication has often evolved through co-

996

Many forms of communication have evolved that prevent animals from coming to harm in what has sometimes been called a limited-

In some cases, communication in the natural world can be deceitful. A male may attempt to convince other males (or a female) that he is bigger (and stronger) than he really is. Possibly one reason that dogs circling in a fight raise the hair along their back is to inflate their apparent size. A potential prey may attempt to convince a predator that it is not, in fact, prey. This form of deceit is especially evident in some species of butterfly that mimic leaves or bark when their wings are at rest. Alternatively, predators may emit deceitful signals to entice their prey. Females of one species of firefly, for instance, mimic the flashes of the females of another species in order to lure males of the second species, which they then eat.