Some forms of communication are complex and learned during a sensitive period.

Bird song is one of the best-known and richest forms of animal communication. Because of the clear connection between what birds hear and how they respond, songbirds have served as a model system in the study of learning and communication. These songs are complex sequences of sounds, often repeated over and over. Like cricket and frog calls, bird songs are advertisement displays, behaviors by which individuals draw attention to their status. For example, the displays might indicate that they are sexually available or are holding territory. Bird songs are typically produced by males in the breeding season.

This sex difference in patterns of communication often results from intersexual selection (Chapter 21), and can extend to other traits. For example, male birds usually have bright plumage and elaborate displays, and females do not. Why do we see such differences between males and females? The key is the level of investment that an individual makes in an offspring. The eggs a female bird produces are metabolically expensive, whereas the sperm a male bird produces are metabolically cheap. Because of this and other costs associated with reproduction, a female typically only has one opportunity or a few opportunities to reproduce. It is therefore in her interest to ensure that she has chosen a high-quality male—one that sings well or has especially fine plumage. By contrast, it is in the male’s interest to maximize his access to females—that is, to be as sexually attractive as possible. Sexual selection therefore tends to produce showy, attractive males and females that choose males on the basis of their performance or appearance.

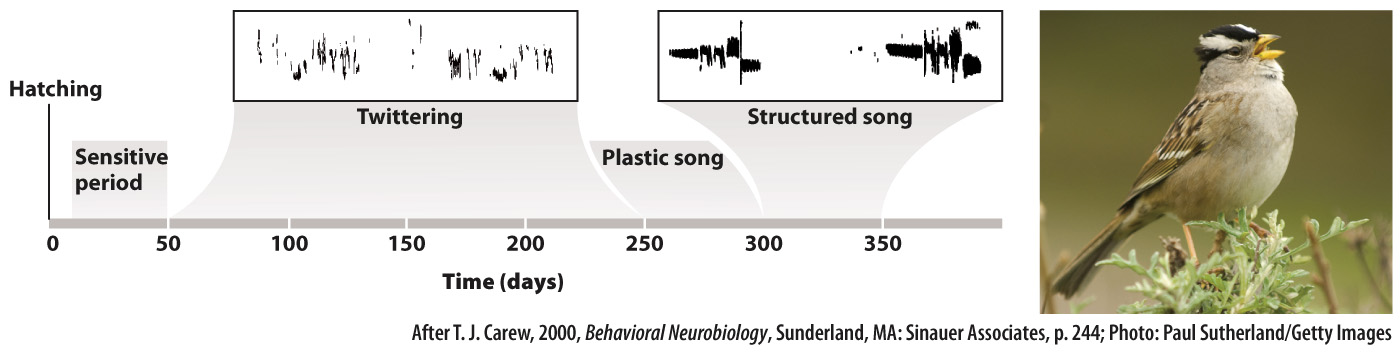

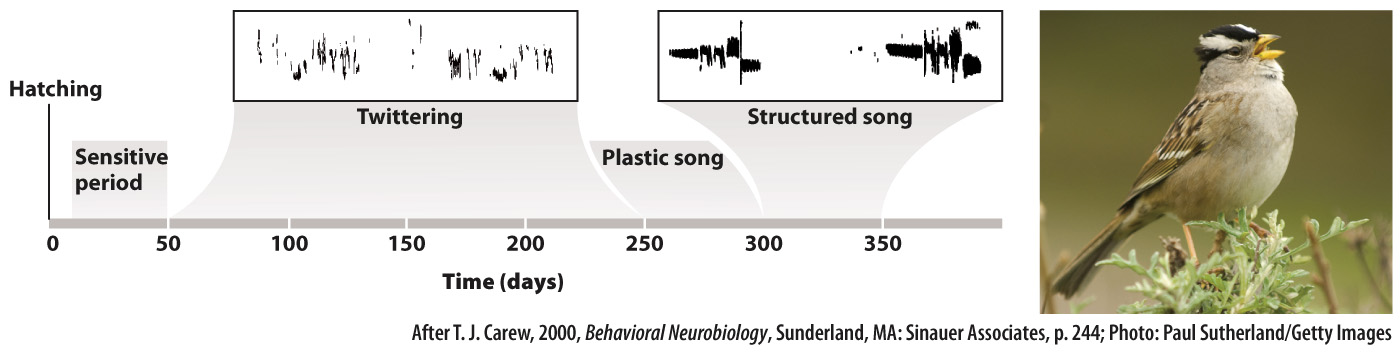

In many species of birds that sing, some or all of the song is learned, often during a specific, sensitive period. Detailed studies of the White-crowned Sparrow, shown in Fig. 45.14, pioneered by neurobiologist and ethologist Peter Marler, and extended by Luis Baptista, have yielded the following general picture of the process.

FIG. 45.14 Song acquisition in the White-crowned Sparrow. Sonograms show differences between the unstructured twittering of early life and the final, structured song.

Song in White-crowned Sparrows is learned by imprinting: The young male hears adult song during a sensitive period, 10–50 days after hatching. Then, shortly afterward, young male White-crowned Sparrows produce unstructured twittering sounds, known as a subsong, comparable to the babbling of human babies. If deprived of hearing adult song, for example by isolation during the sensitive period, the bird sings for the rest of his life a song not much different from unstructured twittering, even if he hears another male sing both before and after isolation.

Between about 250 and 300 days, the male sings an imperfect copy of the song (known as plastic song), and by about 300 to 350 days after hatching, song acquisition is complete (this song is known as structured song). At this point, even if the bird is deafened in the lab, he will still sing correctly. The song he produces is a precise copy of the one he learned, typically by hearing another male’s song during the sensitive period, complete with most of its individual as well as species-specific characteristics.

So White-crowned Sparrows have a programmed predisposition for when song learning takes place. Even more interesting, what can be learned is similarly constrained. If a tape of another species’ song is played during the sensitive period, even the song of closely related Swamp Sparrows, the White-crowned male cannot learn that song; his adult song ends up not much different from his unstructured twittering. However, if he is provided with a live tutor, such as a live male Swamp Sparrow rather than a tape, his ability to learn the other bird’s songs is greatly improved. Furthermore, if he hears tapes of both the song of his own species and that of closely related species played together, he can pick out the correct elements and sing a perfect White-crowned Sparrow song. Thus, birds of this species preferentially learn their species-specific song, but they cannot sing a normal song without learning it from another bird.

Song learning in White-crowned Sparrows has been well studied, and provides just one example of song learning in birds. Some species, such as mockingbirds, starlings, and canaries, learn a wider range of songs than do White-crowned Sparrows, and have a longer period of song learning, in some cases probably lifelong. By contrast, other species, such as many New World flycatchers, apparently have hard-wired (innate) songs. Other sound-based forms of communication, such as those seen in dolphins and whales, are only beginning to be decoded and understood.