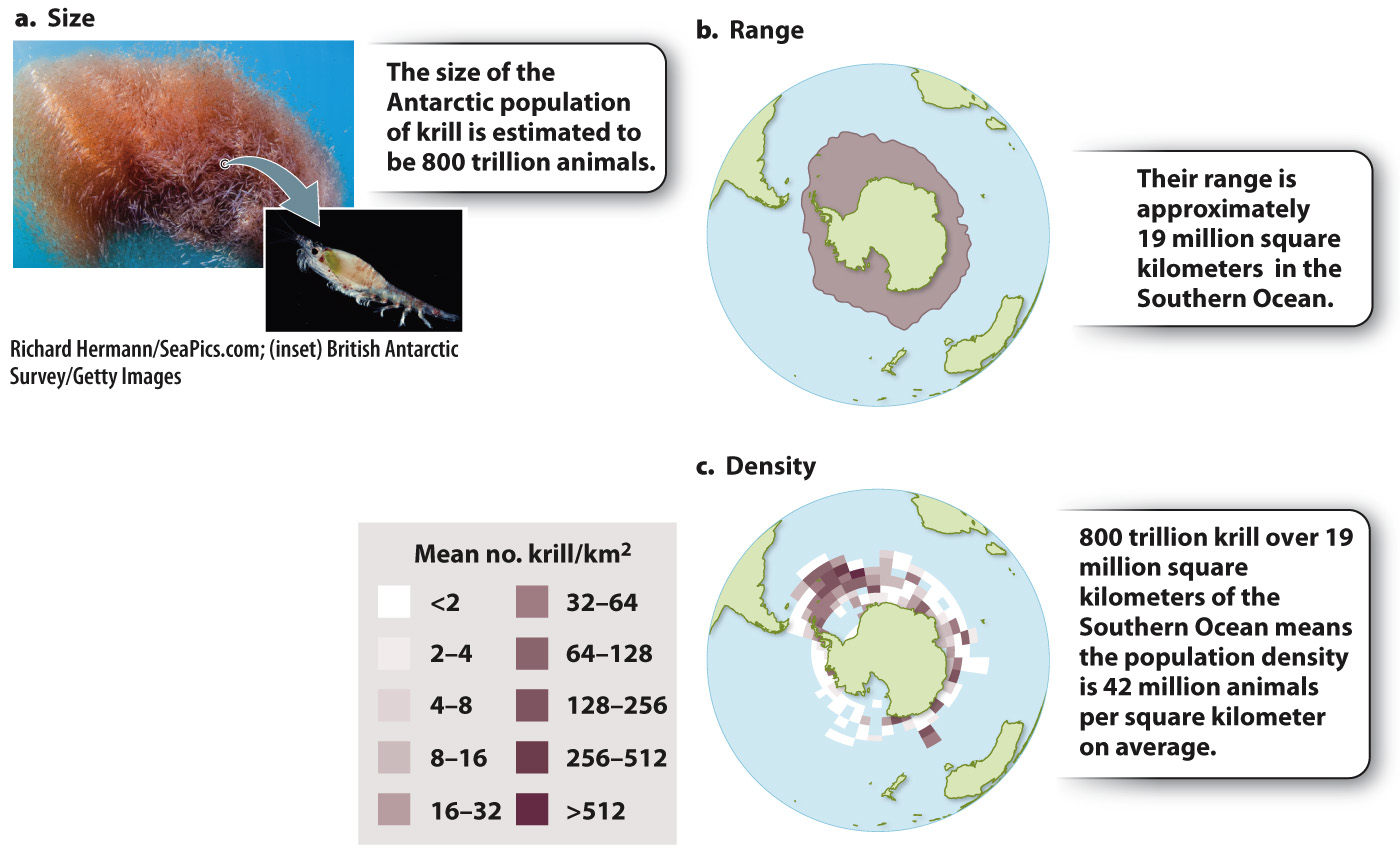

Three key features of a population are its size, range, and density.

Populations are defined by three key features: size, range, and density (Fig. 46.1). Population size is simply the number of individuals of all ages alive at a particular time in a particular place. For example, the population of krill in the cold waters around Antarctica is estimated at 800 trillion, making them by mass the most abundant animals on Earth (Fig. 46.1a).

A second key feature of a population is its geographic range: how widely a population is spread. Fig. 46.1b, for example, shows that the Antarctic krill population lives in an area of 19 million square kilometers around Antarctica. The range of any species reflects the range of climates a population can tolerate and determines how many other species the population encounters. The range of a plant population, for example, influences how many kinds of insect eat it, and the range of an insect population determines how many kinds of plant it encounters.

Taken together, population size and range contribute to a third key attribute of a population, its density. Population density is defined as a population’s size divided by its range. In effect, it tells us how crowded or dispersed the individuals are that make up the population. For the Antarctic krill population, 800 trillion animals spread over 19 million square kilometers yields a density of 42 million animals per square kilometer (Fig. 46.1c). As we will see, population density can affect population size.

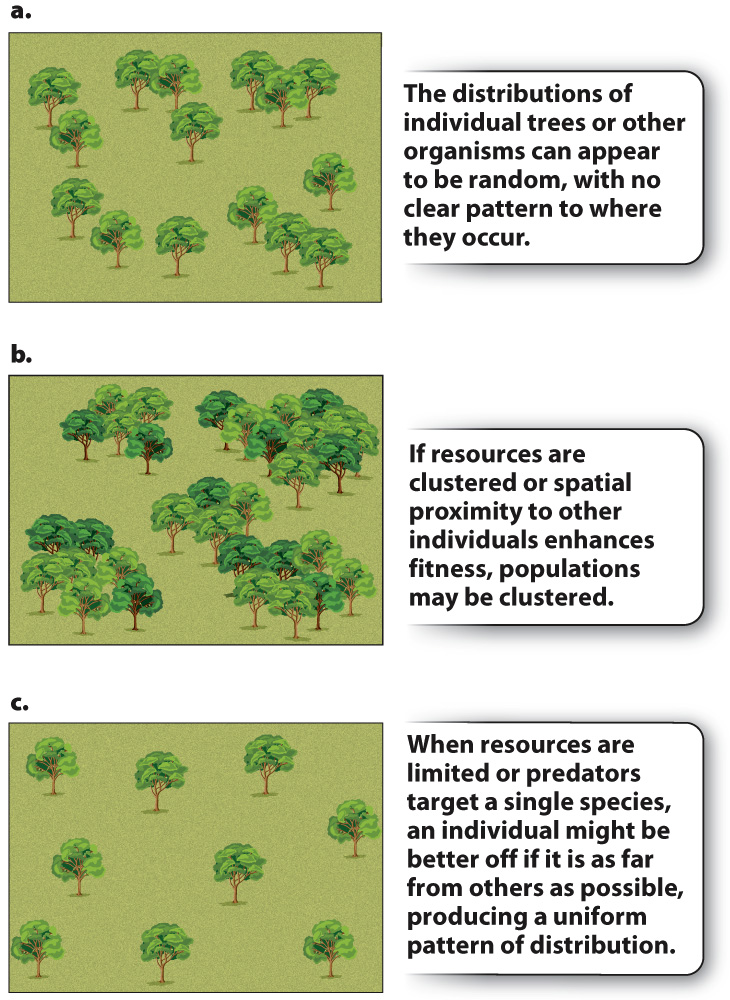

This way of characterizing population density, as average density across the range of a population, is often useful, but it can be misleading depending on how the organisms are distributed (Fig. 46.2). For example, the individuals within a population may be distributed randomly. That is, a new individual has an equal chance of occupying any position within the range, and the location of one individual has no influence on where the next will occur (Fig. 46.2a). Sometimes, however, resources are distributed patchily within the range, or the chances of a new individual’s survival are enhanced by the presence of other individuals. In these circumstances, the population may be clumped, with individuals clustered together (Fig. 46.2b). In still other cases, one individual of a population might prevent another from settling nearby, for example if all individuals depend on the same set of resources. Or predators, having located one prey individual, may search for other members of the same species nearby. Under these conditions, individuals may be distributed more evenly than would be predicted by chance. Ecologists call such populations uniform (Fig. 46.2c).

1006